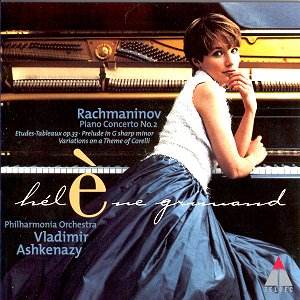

Here is a clear case of marketing gone, if not barking

mad, certainly disturbingly cuckoo. Despite my reservations set out

below, Grimaud is an exceptionally talented pianist whose main virtue

is a sensitive musicianship. So: when one reads the inside back cover

of the booklet, why does one find a whole page entitled 'Mini-poster

Hélène Grimaud'? It is actually instructions on how to

construct your very own stand for the photo of the back cover of the

booklet (a photo remarkable similar to that to the front cover: both

show Grimaud draped over the keyboard of a Steinway) if you take off

the front plastic cover of the case and reverse it. Then, presumably,

you can gaze at it while you listen to the music on the disc, (imagining

Grimaud at work? I doubt that's what they had in mind).

Actually, it's just silly. Grimaud can and should stand

perfectly well on her own ten fingers without props such as this, especially

as this is such a well-planned Rachmaninov disc. Neither, interesting

though it may be, do we really need to know that Grimaud can sees colours

when she hears music (‘Synaesthesia’), especially as it is less intense

when she is playing than when she is listening. So it would appear.

As far as recent issues are concerned, it is perhaps

unfortunate that this comes up against the recent BBC

Legends Moiseiwitsch disc (coupled with Beethoven’s ‘Emperor’ Concerto).

Moiseiwitsch plays with an authority and grasp which are impossible

for Grimaud to match. She is at her finest in the supremely tender second

movement, where she interacts well with the orchestra. Her playing is

always neat and she shows herself to be capable of great delicacy in

all three movements. She also has the ability to perform the musical

equivalent of lifting one's eyebrow, with which she delightfully projects

the scherzando element of the third movement. On the other side

of the coin, she does have a tendency to pick out lines for no good

apparent reason, which can be disturbing: this trait is heard especially

in the first movement. Ashkenazy accompanies sympathetically, the recording

presenting the detail of Rachmaninov’s sometimes thick scoring remarkably

well. The Philharmonia is its usual silken self (the horn solo in the

first movement is particularly beautiful).

The famous Prelude in G sharp minor, Op. 32 No. 12

brings us down to earth again after the pyrotechnics of the Second Concerto’s

finale, although Grimaud is a bit dry (strangely short on pedal for

a piece as evocative as this one). The Etudes-tableaux are better, Grimaud

succeeding in portraying the angry opening of No. 7 well.

The Corelli Variations take us to later in Rachmaninov’s

creative output. Grimaud’s performance is well-characterised, but she

remains too much on the surface: there are deeper elements to be discovered

in this score. She could have been more daring with Rachmaninov’s sonorities:

they are frequently barer, more fragmentary that of the Rachmaninov

of the Second Concerto. They need no apology, for they gain in significance

if presented purely for what they are. This set of variations is one

of the finest of Rachmaninov’s keyboard works: at least it is good to

see it featured on a major international release.

Colin Clarke

![]() Hélène Grimaud

(piano); Philharmonia Orchestra/Vladimir Ashkenazy.

Hélène Grimaud

(piano); Philharmonia Orchestra/Vladimir Ashkenazy.![]() TELDEC 8573-84376-2

[59.47]

TELDEC 8573-84376-2

[59.47]