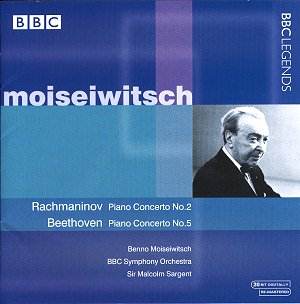

In Benno Moiseiwitsch, at last one encounters a pianist

for whom phenomenal technique is subservient to his equally phenomenal

musicality. It is a combination we can but dream about today, and each

passing competition, or each new face presented by whichever record

company seems to deny the continued existence of such a precious beast.

It is indeed a treat for the record collector that this BBC disc comes

onto the market at about the same time as Solomon’s studio account of

the ‘Emperor’ (with the Philharmonia Orchestra under Herbert Menges

on Testament SBT1221 and recorded in May 1955). Both pianists' accounts

breathe the same integrity, albeit presented with their own personalities.

The explosive opening chords of the ‘Emperor’ set the

tone of the interpretation: the dry timpani strokes only serve to emphasise

this force. There may, indeed, be some blemishes in the ensuing piano

cadenzas (and when they recur later in the movement), but the actual

piano sound is fabulously rich and full. Indeed, Moiseiwitsch is unafraid

to take risks, and as his vision of the whole is so well projected,

such small stumbles hardly matter. Along with these risks comes an astonishingly

wide dynamic range, heard in microcosm in the final chordal sequence

accompanied by timpani towards the close of the final movement, which

moves from almost-martellato fortissimo down to a near inaudible pppp.

The slow movement is beautifully sung, although Moiseiwitsch can admittedly

over-project at times.

Moiseiwitsch enjoyed a special relationship with Sergei

Rachmaninov, and his affection and enthusiasm for that composer’s music

makes his performances memorable. More, the Proms were close to his

heart (he made over a hundred appearances at the annual festival). The

two combine to give a performance of great sweep and force. The opening

chords of the first movement of the Second Concerto are incredibly dramatic,

leading to the ensuing theme on strings, which comes across like an

unstoppable flow of lava. Balancing the drama of the first movement,

the second shows Moiseiwitsch’s sensitivity to subtle harmonic change.

Moiseiwitsch imbues the inner part-writing of the final movements with

a life and character all of their own. More, he has the long-range vision

to stop the approach to the end appearing like a sprint to the finishing

line. Instead, it appears as the logical, and powerful, outcome of all

of the events that have preceded it.

This is a memorable coupling which acts as a reminder

of Moiseiwitsch’s greatness. If only there were pianists like this today.

Colin Clarke