|

|

|

alternatively

CD: AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

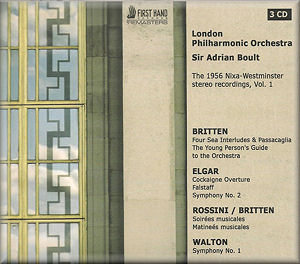

Sir Adrian Boult. The 1956 Nixa-Westminster

stereo recordings, Vol. 1

CD 1

Sir William WALTON (1902-1983) Symphony

No. 1 in B flat minor [43:17]

Sir Edward ELGAR (1857-1934) Falstaff

– Symphonic Study in C minor, Op. 68* [33:48]

CD 2

Sir Edward ELGAR Symphony No.

2 in E flat major, Op. 63 [52:33]

Cockaigne, ‘In London Town’ – Concert Overture, Op. 40 [14:02]

Benjamin BRITTEN (1913-1976) Soirées

musicales, Op. 9** [9:59]

CD 3

Benjamin BRITTEN The Young

Person’s Guide to the Orchestra – Variations and Fugue on a Theme

of Purcell, Op. 34 (Narration: Sir Adrian Boult)** [19:38]

Matinées musicales, Op. 24** [13:13]

Four Sea Interludes Op. 33a and Passacaglia, Op. 33b

(Peter Grimes)** [24:14]

The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra – Variations and Fugue

on a Theme of Purcell, Op. 34** [18:55]

London Philharmonic Orchestra/Sir Adrian Boult

London Philharmonic Orchestra/Sir Adrian Boult

rec. Walthamstow Assembly Hall 15-17 August, 1956; *20 August 1956;

** 30-31 August 1956

FIRST HAND RECORDS FHR06 [3 CDs: 77:05 + 76:34 + 75:59]

FIRST HAND RECORDS FHR06 [3 CDs: 77:05 + 76:34 + 75:59]

|

|

|

These recordings all emanate from a series of sessions that

the American label, Westminster, and their British partner,

Nixa Records, organised in August 1956. One of the first things

to note is their sheer productivity. Many people would consider

that Boult and his players had done a pretty sterling job in

the time available on the basis of the eight works listed above.

However, the same sessions also produced a complete set of the

four Schumann symphonies and all the overtures by Berlioz –

these are promised in a companion volume to be released by First

Hand Records in due course.

Unusually for the period, the recordings were made in stereo

only – according to a most interesting booklet note by Peter

Bromley, mono versions were mixed down from the stereo tapes

for separate issue. Apparently the stereo master tape of The

Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra can’t be traced

so in this set we are offered a stereo version of the score

without narration, transferred from LP, and a mono version, with narration, transferred from the mixed down mono master. FHR assure us that, as far as they know, the mono version with narration was only ever released in mono, and thus no stereo edited version exists.

All these recordings were issued in the USA as stereo LPs by

Westminster but Nixa limited themselves to a partial release

of the material in the UK and on mono LPs only. Most of the

performances have made it onto CD previously but the account

of Cockaigne has never before been released in the UK

in any format.

Before discussing the performances I must say that the sound

quality on these recordings is really very good indeed. True,

there are some instances where the recordings slightly betray

their age but, in all honesty, few allowances need to be made

and one soon forgets that one is listening to performances that

are over fifty years old. Truly, the Westminster engineers did

a first rate job and their skill has been matched by Ian Jones,

who made these transfers.

The performances are well worth preserving, partly for their

quality but also partly because they add to our appreciation

of Boult. His Elgar interpretations are very familiar to collectors

– this set contains, for example, the second of his five recordings

of the Second Symphony and the second of the three recordings

of Falstaff that he made. On the other hand, the music

of Britten featured much less in his recorded repertoire at

least – indeed, I can’t immediately recall any other Britten

recordings by Boult. And Walton was similarly an infrequent

feature in his programmes. I’m sure this is the only studio

recording he made of the B flat minor symphony, though I do

recall attending a concert in Bradford, probably in the late

1960s, when he performed it with the Hallé.

This recording of the Walton symphony has recently been issued

by Somm (review).

I haven’t heard that transfer but I note that my colleague,

Jonathan Woolf, a most experienced judge of vintage issues,

commented that “The recording isn’t, to be honest, any great

shakes even for this vintage”. Perhaps that impression owes

something to the transfer, for I thought the sound offered by

First Hand was decent enough. Having said that, the sound quality

in most of the other performances struck me as being a bit brighter.

It will be noted that the Walton was recorded fairly early on

in the sessions – I wonder if it was the very first recording

made? – and perhaps the engineers refined their work as the

sessions progressed. I used to have this recording of the symphony

many years ago on LP but it was eventually eclipsed by the electrifying

Previn performance on RCA (see

review) and discarded. I think Previn’s account, still my

favourite, eclipses this Boult reading for sheer panache and

verve but I plead youthful misjudgement as my excuse for discarding

Boult completely because now, with better acquaintance with

the score, I can see that his performance has much to offer.

The first movement is more sober than Previn – and some other

versions – but Boult still plays the music with purpose and

ensures that the rhythms, which are so crucial in this movement,

are strongly articulated. One has a sense of patience and feeling

for structure. The scherzo, taken at a good speed, as Jonathan

noted, is well played. However, to my ears it’s just a bit on

the polite side: the essential menace and malice is not quite

there. But Boult comes into his own in the slow movement. His

reading has the necessary intensity and is well controlled.

The main climax (from around 7:00 to 8:14) is very powerful.

I think his reading of the finale is a success too and the fugal

episodes are driven along well. Overall, while this might not

be a library choice it’s a not inconsiderable version and I’m

glad to have rediscovered it.

Boult proves his worth in the Britten items also. Personally,

the narrated version of The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra

is something I can do without at any time – Boult’s narration

is a little bit schoolmasterly but at least he has the virtue

of clarity in his delivery and the words are delivered ‘straight’

with no attempt to draw attention to the narrator. But if I

can do without The Young Person’s Guide, then Variations

and Fugue on a Theme of Purcell is quite another matter.

These are expert and very clever variations and Boult does them

very nicely. Perhaps the trombone and tuba variation is a bit

too stately and pompous – you’d never credit the marking is

Allegro molto! But, that apart, I found his interpretation

most enjoyable and the playing is good too. The recording is

very satisfactory, with the percussion well reported – sample

the xylophone glissandi near the end.

Britten is also in clever and entertaining mode in the Soirées

musicales and Matinées musicales and in these expertly

crafted miniatures Sir Adrian proves that he’s no sober sides.

In several of the pieces there’s a discernable twinkle in the

Boult eye. The LPO respond with lively playing and I enjoyed

these light pieces very much. At the other end of the emotional

scale lie the Peter Grimes pieces. Boult really does

these very well. The rich, sonorous brass interjections in ‘Dawn’

are most imposing – a credit to the engineers as well as to

the performers – and the chattering energy of ‘Sunday Morning’

is well conveyed. Best of all is ‘Storm’ where Boult unleashes

a most convincing tempest. The playing is exciting and it’s

vividly captured by the recording. My ear was caught by the

frightening, dull bass drum around 1:00. It’s good to find the

powerful ‘Passacaglia’ included also and the conductor builds

this music up convincingly.

But if Sir Adrian Boult is not renowned as a Britten conductor,

everyone recognises his eminence in Elgar and here we have three

notable performances that reinforce his reputation. The Cockaigne

will be new to UK collectors at least and it’s well worth attention.

Boult unfolds Elgar’s colourful portrait of Old London Town

with skill and no little flair. He’s just as convincing in Falstaff.

He may not bring the red-blooded panache and character of Barbirolli

(see

review) to the piece but he does bring to it a fine sense

of structure and he characterises the music strongly. It’s a

colourful and vivid performance in which Boult is aided and

abetted by some acute, lively playing by the LPO. The recorded

sound seems brighter to me when compared with the Walton performance

and the horns register more successfully here. On the debit

side the percussion is sometimes too closely balanced, notably

in the ‘Falstaff’s March’ section (CD 1, track 8). It seems

to me that Boult conveys very successfully the invention and

wit of Elgar’s music. He captures the pathos too and the closing

pages are done very well. I don’t know if this recording represented

a single ‘take’ – probably not – but it sounds like one.

The stand-out performance in the set, however, is that of the

Second Symphony. I don’t know why but I realised that I hadn’t

listened to the symphony for quite a while. The fine performance

reminded me how much I love and admire this wonderful work.

The first movement is superb, right from a surging, confident

start at an excellent pace. Throughout the movement Boult is

in total command of the structure and, crucially, shows a masterly

control of the ebb and flow that’s at the heart of Elgar’s music.

The slow movement is a noble elegy, which he shapes with complete

understanding. The LPO plays with great feeling, not least in

that wonderful passage (from 7:37) where Elgar pits a gently

keening oboe melody in triplets against the main theme, quietly

intoned by the horns. Here Boult conveys patrician sadness.

This is as fine an account of the movement as I can recall hearing.

The fire that wasn’t quite there in the scherzo of the Walton

symphony is properly present in Elgar’s scherzo. From 4:30 onwards

the build-up to the percussion-dominated climax is held under

control and throughout the movement, as well as putting across

the exciting passages Boult is a master of light and shade.

The final pages, with the horns shooting off like musical sky-rockets,

are very exciting. The finale is handled with understanding.

Everything sounds just right and inevitable. Boult keeps the

momentum going very well, though he’s alive to the autumn tints

in the music also. The closing pages (from 10:51), where the

“Spirit of Delight” motif returns, are expertly handled. Michael

Steinberg has drawn a parallel between these pages and the closing

moments of the Brahms Third, one of Elgar’s own favourite pieces.

I think there’s a lot in that and it registers particularly

strongly when one hears the music conducted by someone who was

also a noted interpreter of Brahms (see

review).

This is a splendid set, which all admirers of Sir Adrian Boult

should hear. As I said at the start, the sound quality is remarkably

good. The presentation is first class, with two good and informative

essays and some evocative black and white session photographs.

First Hand Records have done us a great service in making these

recordings available again and in doing such a fine job over

the transfers and presentation. I look forward keenly to the

next volume.

John Quinn

And a review from Rob Barnett:-

Listening to Boult's bitingly vital Walton points up the expansive

qualities given priority by William Boughton in his recent recording

on Nimbus.

For all the analogue vinegar of the 1956 stereo recording there's

no denying Boult's drive and chiselled precision. The whole

thing is through in 43:17 against Boughton's 46:45. Boughton

is not poor by its side but its strengths differ. It leans towards

detail and the mile-wide span rather than the emotional vortex

favoured by Boult. Boughton scores in the finale in bringing

out the music’s epic aspects.

Boult zips and zaps his way through the Scherzo with

the prescribed ‘malizia’ and the horns have a relished metallic

throatiness. Yes, there is the usual analogue background 'shush'

but it is even, unchanging and uncontoured. On the other hand

those final Boult hammer-blows are fragile rice-paper parchment

– unsurprising by comparison with Boughton's full-spectrum modern

recording.

Boult’s Falstaff shares the virtues of his Walton 1.

It positively sprints along and while lacking the romantic glow

of the famous Barbirolli 1966 recording it is a tonic - so vivid,

so sharply etched, chiselled and goaded forward. The recording

renders every detail crisply. The edgy trills of the tambourine

at 3:48 are just one delight among many. The engineers also

draw in page-turns and chair creaks; no harm in that. Even so,

as an interpretation, it has to take a step down to Bernard

Herrmann's most impressive and superbly coloured CBS Falstaff

from the 1940s - issued on Andrew Rose's Pristine label.

Elgar 2 is deftly handled by Boult who brings to the reading

a weighty determination. The level of sheer verve is high and

the whole approach is invigorating and in keeping with the Walton.

While it is not as wild and woolly as the Solti on Decca

this is Boult at his warmest and keenest. In the finale those

off-beat syncopated blows are as exciting as any version Boult

recorded. The 1944

BBCSO version is reputed to be his most vital but for me

this 1956 reading stands at an apex in the Boult discography.

Boult's 1950s Nixa Cockaigne is full of tempestuous power

as we hear in the little whirling string figures in the first

minute. It’s fascinating effort and grand music making though

I still prefer Barbirolli’s EMI studio tape (see

review).

The Young Person’s Guide is in a single 18:55 track and

is in wheezy stereo. The Soirées Musicales is zestful,

artful, sentimental, balletic, and in the case of the tr.9 fully

up to Tchaikovskian standards with castanets and no holds barred

Spanishry. The Matinées Musicales are in the same frivolous,

precise and balletic mood-frame as the Soirées. The sound

is ‘blasty’ in tr.10.

The Grimes Interludes and Passacaglia are finely

done but with the analogue ‘shush’ rather more in evidence.

The only real downside is that the bass is a shade muddy which

does not strengthen the Storm movement. Interesting as

a reading but Previn delivers with greater virility and is blessed

with superb analogue from almost two decades later than Boult.

I have always loved the ‘Grimes’ Passacaglia – effectively

a symphonic episode in compressed form. It's wonderfully atmospheric

with an utterly compelling stride. For Britten this untypically

emotional piece reaches towards Barber's great orchestral interludes:

the Essays

and the Shelley

Scene. One of Britten's finest productions, for me, it ranks

alongside the Sinfonia da Requiem and Our Hunting

Fathers. The viola adds a rasping Greek chorus to the proceedings

whose Suffolk centre of gravity is brought home by the arcing

woodwind and brass chatter arising from 1.00 to 2.00. It’s superbly

done but cannot escape the constraints of 1950s technology.

Previn on EMI

is immensely enjoyable given his much more succulent and refined

sound.

The first version of YPG on CD 3 has Boult narrating over the

music - the whole thing in mono. Boult is dignified and kind.

What a delight to hear English spoken in this way though no

doubt some will find it stilted. Then at end of the CD the Guide

is reprised but this time in splendid stereo. In this case the

disc divides each variation into separate tracks. I was surprised

by how well the recording sounded.

The three CDs are housed, each in their own pocket, in a four

segment foldout card casing of the type favoured recently for

Brilliant Classics budget releases. The fourth fold carries

the booklet. It’s also rather like the design favoured by Sony

for their recently issued ‘Music of America’ series.

The liner booklet is in English only favouring bold simplicity

in which substance rather than the design play-pit is the objective.

The track details are fully listed and session dates, locations

and catalogue numbers of the original LP issues are cited. The

music notes are lucidly handled by Colin Anderson while Peter

Bromley provides the Westminster label history. For those steeped

in nostalgia FHR treat us to reduced images of the covers of

the original LP sleeves. Both booklet and sleeve are liberally

decked out with session candids which add to the period flavour

and through which we see the technical team of Kurt List, Herbert

Zeithammer, Ursula Franz and Mario Mizzaro at work.

This First Hand Recordings set of transfers largely taken from

the original analogue tapes is marked ‘Vol. 1’ so we can hope

perhaps that the complete Boult Sibelius tone poems, dating

from the same era, will follow. We know from the Somm and Omega-Vanguard

transfers that those Sibelius tone poems share with this Walton

1 a tension and sharpness that redound to everyone’s credit.

While there is the faintest leaning toward shrillness and the

breadth and richness of bass is limited these are tirelessly

exciting readings. The recordings have never sounded as good.

Rob Barnett

|

|