see also

Montague

Phillips Orchestral Music Volume 1

This is not the forum

to discuss the life and times of Montague

Phillips. There is a fine article on

Musicweb by Philip Scowcroft

which touches on these topics. I presume

that with the greater interest in his

music someone will be inspired or invited

to write the standard biography.  It

is the kind of little volume that would,

once upon a time, have been produced

by Thames Publishing. In the meantime

I offer this discussion on the second

volume of orchestral works which has

recently appeared on the Dutton CD label.

It

is the kind of little volume that would,

once upon a time, have been produced

by Thames Publishing. In the meantime

I offer this discussion on the second

volume of orchestral works which has

recently appeared on the Dutton CD label.

This issue is of great

interest for a number of reasons. Firstly

it largely completes the cycle of orchestral

works from Phillips’ pen. There are

a few lacunae, such as the Boadicea

Overture, but by and large everything

of importance is present and correct.

A little more will be said about the

two piano concertos at the end of this

essay).

Another reason this

release interests is the broad spectrum

of music presented – from a miniature

character sketch called In Old

Verona to what is in effect a miniature

violin concerto; from an orchestration

of one of Phillips’ piano suites to

two of the best concert overtures in

the repertoire. Volume One explored

the remains of the Symphony and the

complete Sinfonia.

I plan to consider

these works in loosely, but not quite,

chronological order.

Phantasy for

violin and orchestra Op.16

The earliest work on

this CD is the Phantasy for Violin and

Orchestra Op.16 which was written in

1912. In some ways it is quite hard

to imagine that this work was actually

played at a Promenade Concert – not

because of the quality of the music,

which is superb – but simply because

of our association of this composer

with ‘light music.’ However this work

is no lightweight or trivial piece.

Sometime in 1906 William

Walter Cobbett announced his first Chamber

Music Prize in the Musical Times. This

called for relatively short pieces of

music that reflected the string writing

and form of the ‘fantasies’ of Jacobean

and Elizabethan music. Of course we

know that over the years this competition

produced a large number of works by

famous and not so famous composers.

It is easy to think of fine examples

by the Five Bs: Bax, Bowen, Bridge,

Britten and Bush for starters.

I think that the programme

notes are slightly disingenuous in their

description of the Phantasy.

Lewis Foreman states that this music

reflects a pre-war innocence- which

it most certainly does – but he further

notes that it lacks ‘any reflection

of the angst and crisis of the times.’

In those strange years before the Great

War society seemed to be oblivious to

the coming conflagration. It was as

if people were deliberately ignoring

the terror that was about to be unleashed.

But in another sense there was an ‘end

of term’ feel about the times. The old

order was about to crash down and people

were perhaps subliminally aware of this.

It was the innocence that stopped them

going mad. However note that the innocence

of Montague Phillips’ Phantasy

is always balanced by a feeling of impending

change – nostalgia for an era that was

passing. Angst was probably not a requirement

at this stage.

The piece opens rather

darkly – in fact it is quite unlike

most of the composer’s output. Suddenly

the solo violin arrives with a heart-easing

cadenza – quite a contrast to the first

few bars. The orchestra asserts itself

before giving way to another short cadenza.

This leads to a slow romantic theme

that is certainly the heart of the work.

Without doubt there is a definite nod

in the direction of Elgar. Yet through

this intensity there are moments of

repose and even a few bars of relaxation.

The composer gives the soloist some

stunningly beautiful figurations to

play whilst the orchestra concentrates

on the main event.

The music changes pace

and becomes a little faster although

the romantic theme keeps trying to reassert

itself. Soon there is an intense fast

section that hits a big climax complete

with timpani and full brass chorus.

Out of this comes a lovely song for

the violinist. It has to be said that

the instrumental writing is impressive

and reveals an understanding of the

violin and its capabilities. It is certainly

not an easy solo part.

Soon there are some

unusual modulations - at least for Montague

Phillips - as the soloist muses on past

themes. The tension eases off and the

gorgeous scalar figurations mentioned

above make their final appearance. Soon

we are into the last reflections. The

violin reprises the romantic theme –

this time as a ‘high’ melody. One last

outburst from the orchestra leads to

lovely harmonies supporting the soloist’s

last thoughts on the heart-easing tune.

The work closes with due peace and repose.

This Phantasy

gives us a major insight into the serious

side of the composer. It lets us see

what may have been the direction of

his career if he had concentrated on

concert music and had rejected the path

of songs for the salon.

The work was first

performed at a Queen’s Hall Promenade

Concert on 16 October 1917. The soloist

was Arthur Beckwith, with the composer

conducting the New Queen’s Orchestra.

In May Time Op.38

In my review of Volume

1 of Montague Phillips’ orchestral works

I recalled how I had been introduced

to his music through his songs – in

particular Through a Lattice Window

and Sea Echoes. Since those far

off days I have kept an eye open for

more of Phillips’ works, especially

those written for piano. Unfortunately

they seem to be a little bit scarce

in the second-hand music shops. However

I have been lucky enough to peruse the

Three Country Pictures, the Village

Sketches and the Dance Revels.

Now the beauty of these works is that

they are playable by the so called ‘gifted

amateur.’ As I recall, they are not

great works of art, but are attractive

pieces that are skilfully written and

lie well under the hands. The ‘suite’

format was pretty well widespread in

the first half of the 20th century.

We need only think of Felix Swinstead,

Thomas Dunhill and of course, that master

of the form, Eric Coates.

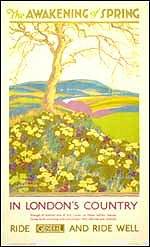

In May Time

is a good example of this particular

genre. It was originally composed for

the piano and was orchestrated by the

composer in the mid-1920s. Lewis Foreman

points out that the original score was

written for very young piano students

– and I am sure he is correct. However

the transcription has a subtlety about

it that belies this innocent genesis.

There are four attractive movements

entitled: On a May Morning, Daffodil

Time, Spring Blossoms and May-time

Revels. The first performance appears

to have been given by Dan Godfrey and

the Bournemouth Municipal Orchestra

in that town on 4 May 1924. An appropriate

date indeed!

One criticism, perhaps,

of this suite is that the four movements

suffer from sameness. It lacks an obvious

slow movement.

The starting point

appears to be the dances from the composer’s

opera, The Rebel Maid. Perhaps

there is also a nod or two in the direction

of Sir Arthur Sullivan and Merrie

England by Edward German.

There is no need to

read any kind of programme into any

of these pieces – except to recall that

Montague Phillips lived in Esher, which

in those days were closer to the countryside

than is the case in 2005. The composer

always responded to the rural environment

and this work is no exception. It is

a charming portrayal of the mood of

an English spring day.

The work opens with

an attractive dance-like movement -

On a May Morning - that contrasts

the strings and woodwind in the principal

tune. The middle section is completely

different – will o’ the wisp woodwind

figurations that compete with a romantic

tune on the violins. Soon the opening

material returns with great gusto. There

are a few allusions to the big tune

before the movement closes with a short

coda.

Daffodil Time

is perhaps the slow movement: ’graceful’

would be the operative word here. In

spite of the fact that this is a bit

more reflective than the other three,

it is still hard to suppress images

of the happiness and the hope of spring.

Spring Blossoms

is the cutest movement. There are pretty

tunes and counter-melodies aplenty.

The middle section is an attractive

theme which is played over and over

again – always supported by woodwind

fluttering above the melody. Perhaps

the first butterflies are on the wing?

Spring Blossoms ends quietly.

May-Time Revels

probably owes most to the Rebel Maid.

It is a good going dance from start

to finish – complete with percussion

and fine brass playing. There is a short

reflective middle section that dances

its way to the restatement of opening

the ‘Allegro con Spirito’ material.

Hillside Melody

Op.40

The Hillside Melody

is a fine example a ‘light’ tone poem.

One cannot help feeling that this score

could have been written for, or perhaps

fitted round a film score. In particular

I can imagine one of the British Transport

Film group’s offerings about the Home

Counties. It is not too fanciful to

see musical images of places like Leith

Hill and the Surrey hills. The score

exudes country things – perhaps sports

or maybe just a ramble in the woods.

Here a Green Line bus arrives from the

city and perchance a horse and rider

are making their way along a rather

secret bridleway. Or maybe two lovers

are walking arm in arm over Box Hill.

It

is easy to say that Phillips was influenced

by Percy Grainger in some of his music:

and of course Fred. Delius is never

too far away. But this work was not

written for the highbrow concert hall

– it was composed for smaller ensembles

playing music at the end of the pier

or perhaps the bandstand.

It

is easy to say that Phillips was influenced

by Percy Grainger in some of his music:

and of course Fred. Delius is never

too far away. But this work was not

written for the highbrow concert hall

– it was composed for smaller ensembles

playing music at the end of the pier

or perhaps the bandstand.

Yet although the pictures

invoked are quite definitely South of

England there is an Irish touch in this

music. A friend of mine remarked that

she could hear allusions to the Londonderry

Air in some passages of this work. However

it does not pay to get too engrossed

in trying to unpick references and sources

in a piece like this. It is sufficient

to note that it is a satisfying work

that conjures up a number of happy images

in the mind’s eye. Who can ask for much

more than this?

In Old Verona

In my younger days

the piano stool at home was full of

pieces of music that had descriptive

titles – often referring to romantic-sounding

places. I am not quite sure if many

of them actually fulfilled the expectation

of their various titles – but often

they were pleasant to play and enjoyable

to listen to. It gave a little bit of

warm inspiration when outside the freezing

fog was curling round the corner of

the gasometer. In Old Verona

is a good example of one of these pieces

– albeit conceived for the orchestra.

It is actually an attractive ‘serenade

for strings’ that had the soubriquet

attached by the composer for its publication

in 1950. Now I am not sure if ‘Verona’

immediately springs to mind with this

particular dance tune. There is little

here to remind me of the glorious Ponte

Pietra, Juliet’s Balcony or the Roman

amphitheatre. But that is not the point.

The work is actually an accomplished

essay in writing for strings that is

effective and way beyond the limited

scope of a salon piece.

The short movement

opens with a good tune supported by

a pizzicato base. It is quite a stately

dance. However the mood does change

in the central section. Things become

a little more passionate – perhaps reflecting

the Shakespearian connection? There

is quite a nice rounded climax, before

the music sinks back to the opening

measures. It finishes quietly with a

violin solo.

This is exactly the

kind of music that does a sterling service

for ‘light music.’ Here is nothing complicated

or profound: it is not even a tone poem.

What it does reveal is a composer who

was able to provide a well crafted,

tuneful and enjoyable miniature.

Charles II Overture

Op.60

The listener does not

need to be a historian to enjoy what

is probably one of Montague Phillips’

masterpieces – the Charles II Overture.

However an understanding of some of

this great king’s achievements will

certainly add to the perception of this

work.

For one thing the King

had a reputation as a fun-loving monarch

who presented a complete contrast to

the dour and quite oppressive atmosphere

of Cromwell and his Commonwealth. It

was the age that we can perhaps refer

to as ‘Merry Olde England’. The king

enjoyed the sporting life, in particular

horse racing. But it was not just entertainment

that inspired him. He was a great patron

of the arts and sciences. He launched

a major rebuilding of that bastion of

pageantry, Windsor Castle and laid the

foundations of the Greenwich Observatory.

He was patron for the Chelsea Hospital,

founded for war veterans who even today

wear their distinctive uniforms. He

founded the Royal Society. But perhaps

most significantly for the architectural

skyline was his support of Sir Christopher

Wren’s design and building of St Paul’s

Cathedral. Of course there was the down-side

to his reign – he had to face the immense

problems caused by the plague and the

Great Fire of London.

And there was the romance

too. Throughout his reign he had a string

of ‘lady friends’ the most famous of

these being Nell Gwynne. He was the

father of some 13 illegitimate children,

all of whom he supported financially.

All of this activity

is well described in this overture –except

perhaps his fecundity! I accept that

in many ways it is like a film score.

Not so much the costume dramas that

the BBC would make nowadays – but more

the nineteen-fifties. It is not too

difficult to imagine the images flicking

past in an early example of glorious

‘Technicolor.’

The works starts immediately

with a vigorous upbeat opening – it

could almost be described as swashbuckling.

There is definitely something of the

sea about it. Soon there are some pseudo

fanfares suggesting the approach of

the Royal Party. However this mood dies

away quickly and is replaced by what

may be regarded as the heart of the

overture.  With

music that is totally worthy of Sir

Edward Elgar the mood becomes romantic.

This section perhaps alludes to a secret

meeting between Charles and Nell Gwynne

at ‘The Dove’ public house in Hammersmith?

Or maybe it is a view of Windsor Castle

across the Great Park? Who knows? But

this romantic string theme quite takes

hold of the work. There is something

about this music that reminds me of

Percy Whitlock’s Organ Symphony, although

I doubt any cross-influence; it must

have been the music that was in the

air at this time. Both works were composed

in 1936. The romantic mood subsides

a bit only to be replaced by a short

passage for ‘string quartet.’ After

some harp arpeggios the music gets back

into the swing again. A rather good

fugato for strings leads into music

of pageantry. After another lull the

bustle and ceremonial begins for the

last time. With music that William Walton

would have been proud to have composed,

the overture reprises the opening material

and a last restatement of the romantic

theme. The build up to the impressive

coda is made all the more impressive

by the effective brass writing. The

work concludes with the listener totally

engulfed with joi de vivre. Long

Live the King!

With

music that is totally worthy of Sir

Edward Elgar the mood becomes romantic.

This section perhaps alludes to a secret

meeting between Charles and Nell Gwynne

at ‘The Dove’ public house in Hammersmith?

Or maybe it is a view of Windsor Castle

across the Great Park? Who knows? But

this romantic string theme quite takes

hold of the work. There is something

about this music that reminds me of

Percy Whitlock’s Organ Symphony, although

I doubt any cross-influence; it must

have been the music that was in the

air at this time. Both works were composed

in 1936. The romantic mood subsides

a bit only to be replaced by a short

passage for ‘string quartet.’ After

some harp arpeggios the music gets back

into the swing again. A rather good

fugato for strings leads into music

of pageantry. After another lull the

bustle and ceremonial begins for the

last time. With music that William Walton

would have been proud to have composed,

the overture reprises the opening material

and a last restatement of the romantic

theme. The build up to the impressive

coda is made all the more impressive

by the effective brass writing. The

work concludes with the listener totally

engulfed with joi de vivre. Long

Live the King!

Listeners to the first

Dutton CD will have already been introduced

to the slightly later work, the Revelry

Overture. Lewis Foreman was of the

opinion that this was one of the finest

pieces of its kind in the repertoire.

I agree with him; however I do feel

that this present work has the edge.

It is impossible to say why – both are

fine examples of their genre.

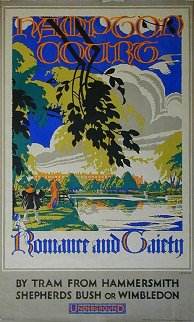

Hampton Court Overture

Op.76

Apparently Charles

II occasionally visited Hampton Court,

in spite of a preference to his newly

enlarged Windsor Castle – so perhaps

it is appropriate to couple Montague

Phillips’ eponymous overture on this

present CD? However the mood of this

work is not actually to do with Royalty

or the Restoration.  It

is much more a celebration of the holiday

mood. In particular, the exodus of Londoners

‘up the Thames’ to this well known house

and gardens. The composer has written

about this work as follows: - "[I

wish] to portray the summer scene at

Hampton Court, the gaiety of the holidaymaking

crowds by the river, and all the pageantry

and beauty of the Palace and its gardens."

It

is much more a celebration of the holiday

mood. In particular, the exodus of Londoners

‘up the Thames’ to this well known house

and gardens. The composer has written

about this work as follows: - "[I

wish] to portray the summer scene at

Hampton Court, the gaiety of the holidaymaking

crowds by the river, and all the pageantry

and beauty of the Palace and its gardens."

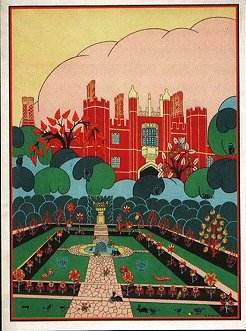

The work opens with

a tune full of energy: percussion and

brass are well to the fore. This is

really ebullient music. Fanfares lead

into a more relaxed statement of the

theme on the woodwind. Soon the opening

music returns. A little catchy rhythm

leads into a slightly more ‘ceremonial’

tune before the meditative material

is given a first airing. It must be

said that this tune is reminiscent of

Sir Edward Elgar without being a direct

crib. I can imagine a boy and girl walking

hand in hand by the riverside or perhaps

sitting in some sunny corner of the

gardens. The mood soon changes to one

of playfulness. Lots of fun – perhaps

children playing chases in the maze?

Soon the music builds to a restatement

of the main theme. Yet soon there is

to be a change of mood as the music

moves into the closing pages. Soon the

playfulness is put to one side and the

ceremonial theme re-establishes itself.

Perhaps here we have a reflection of

royalty and Charles II himself. I understand

that if it had not been for the Restoration,

Oliver Cromwell was about to sell the

Royal Parks for ‘real estate’. So we

have a lot to give thanks for the next

time we enjoy a day at Hampton Court.

This overture is the

latest work represented on this disc.

In fact according to the brief works

list available on Musicweb, it is the

last major work. It is dated 6 April

1954. The first performance was given

in May of the following year with Gilbert

Vintner conducting the BBC Midland Orchestra.

Empire March

Op.68

The Empire March

is not a pastiche of William Walton’s

Crown Imperial or Edward Elgar’s

Pomp and Circumstance or Imperial

Marches, yet there is definitely

a nod in this direction. The work was

first given at a Promenade Concert at

the Royal Albert Hall on the 15 August

1942 and was conducted by Sir Henry

Wood.

The march opens with

a rousing first theme. This is characterised

by clarity of material and a certain

incisiveness of part-writing that is

perhaps unusual in ‘concert marches’.

However we soon arrive at the inevitable

big tune which is actually quite gorgeous

and moving. There is a hymn-like quality

about it without the implied religion.

After a few mock fanfares the opening

theme re-establishes itself - but with

some variation. The inevitable build-up

begins leading to the reprise of the

‘trio’ theme. This time it is played

‘ff’ with full organ accompaniment.

After a final flourish the march ends

in triumph.

Of course Britain no

longer has an Empire – perhaps even

in 1942 the philosophy of Empire was

nearly evacuated of meaning. Yet the

war was at its nadir – and the Commonwealth

of Nations and the Allies were fighting

to retain the freedoms associated with

all that was great about Britain’s achievements.

In those dark days victory was not yet

guaranteed.

This march is as good

as many that have been composed over

the years. If it had been written by

Elgar or Walton it would have been a

‘favourite’ with the musical public.

We are lucky to have it included on

this CD.

Festival Overture

(In Praise Of My Country)

Op.71

It is perhaps quite

difficult to imagine the music of Montague

Phillips being played at the Proms.

Now this is not to make a subjective

or even derogatory comment. But it seems

that a composer, whom we associate with

songs and the operetta The Rebel

Maid, would not be in the same league

as Walton, Vaughan Williams and other

‘heavy’ composers. Yet Phillips had

a series of three works commissioned

for the Promenade Concerts. We have

considered the first of these works.

The Empire March above. The second

commission was the Sinfonietta

which was released on the CDLX 7140.

But the last of the three is the ‘In

Praise of my Country’. The title

of this work is no longer politically

correct, but in any case it was written

in 1944 when the war was beginning to

go the way of the Allies. It received

its first performance on 26 June 1944,

just a few days after the successful

Normandy Landings; the work had been

completed by the end of May of the same

year. This work is quite simply a wonderful

tribute to Great Britain in wartime.

It reflects on two key areas of the

nation’s life – the effort required

to win the war and the beauty of the

nation that so many people were fighting

and working to protect. It is curious

that at the end of 1952 the work’s name

was changed to the Festival March.

However in this CD both titles are attached

– so we can take our choice.

The work is fundamentally

in ternary form with a slow middle section

being surrounded by fast energetic material.

There is actually a quiet opening which

soon builds into a brisk exposition

that is quite definitely ‘full of beans’.

It is ‘construction’ music. If this

was a film score we would be witnessing

men and women building things – planes

or ships or pre-fabs. It is ‘winning

the war’ music. Much of this first section

could never be classified as ‘light

music’ – even if it is not at the cutting

edge of avant-garde. The composer makes

effective use of brass and percussion

including the xylophone, which adds

considerable colour. If I were honest

I would say that the opening three minutes

nod to Walton – but that is no criticism.

It is perhaps not quite as acerbic as

the music the Oldham composer would

have written.

Soon things calm down

and after some musings a gorgeous pastoral

tune for the oboe appears. Yet I am

not sure if this is an English melody

– however it is what the composer will

do with the material that counts most.

The theme is soon taken up by the orchestra

and developed in a fetching manner.

The mood changes once again – there

are some string tremolos before the

‘work’ music re-establishes itself –

this time with a lumbering base that

reminds me of the scherzo of RVW’s Fifth

Symphony. There is a little deliberation

in the orchestra – as if it is trying

to form an opinion, yet soon the inevitable

build-up begins. There is a brassy choral

followed by a reprise of the oboe melody.

This time it is represented with soaring

strings with brass comments. Soon the

work comes to a triumphant and glorious

close. The war may not yet be won –

but there is a feeling that all will

be well. This is a great and uplifting

work that perhaps only suffers for being

a child of its time.

Conclusion

This CD allows us another

chance to explore the music of Montague

Phillips. It enables us to try to make

a balanced judgement on his status as

a composer.

In my essay on the

first volume of CDs I noted a number

of characteristics of his music. These

included the fact that the music was

definitely tuneful; that it was well

constructed and composed; and perhaps

most pertinently, that it is thoroughly

enjoyable.

From an emotional point

of view most of Phillips’ works engender

a sense of well-being and perhaps even

self indulgence. Innocence is maybe

the best adjective to describe the prevailing

mood of most (but certainly not all)

of these works.

The disc allows us

to consider the dichotomy between what

is commonly called ‘light music’ and

‘high-brow.’ Montague Phillips once

said that he composed works for the

‘great majority of people who lie between

the ultra high-brows and the irredeemable

low-brows and who can appreciate music

that is melodious and well written but

not too advanced’.

Beside the inevitable

In May Time suite and the ‘popular’

overtures there is the Phantasy for

Violin and Orchestra. As I noted

above this is a serious work – composed

for the concert hall rather than the

end of the pier. Further, this CD allows

us to evaluate two works composed for

the Promenade Concerts in the 1940s.

In particular the Festival Overture

demands our attention as a significant

work.

So although I would

still characterize Montague Phillips

works as certainly not being high-brow

and usually having that innocent quality,

I would encourage listeners to consider

the composer as one capable of writing

in a number of styles and moods.

I was talking to a

well known musicologist a few weeks

ago and he told me some heartening news.

Apparently a record company is due to

release both of Montague Phillips’ piano

concertos. This will be a major event

in British Music. I have never heard

these pieces and I doubt many people

alive today have. This release will

give a fine opportunity to hear two

major concert works by a composer normally

regarded as a ‘light music’ practitioner.

Furthermore it will mean that the vast

majority of Montague Phillips’ orchestral

music will be readily available to listeners.

This is a situation that could hardly

have been imagined a year or so ago.

John France

Montague

Phillips Orchestral Music Volume 1