see

also Volume 2

Montague Phillips and

I go back a long way. In fact, I first

came across him in Llandudno about a

third of a century ago. I had recently

discovered the delights of English music

and was beginning to assemble a collection

of records and piano sheet music. In

Mostyn Street there was a wonderful

second-hand bookshop. I believe it is

still there. It was an Aladdin’s Cave

for both me and my father. He was soon

engrossed in the poetry section and

I found the cupboards full of music.

It took me a fortnight to inspect all

the music that ‘Di the Book’ had in

his shop. Of course I bought all sorts

of stuff. Some of it was good, some

bad and some downright indifferent.

Plenty of piano music I could not play

then and still cannot play. Yet it was

cheap; a few shillings for handfuls

of the stuff. My father had found the

collected works of that great Lancastrian

Poet, Francis Thompson and was clearly

delighted. I had found some songs by

Montague Phillips which appealed to

the romantic streak in my boyish nature.

These were ‘From a Lattice Window,’

and, if I remember correctly ‘Sea

Echoes.’ Of course, I had to wait

until I returned to school before I

could try them out with one of the sixth

form girls who sang a bit. Something,

though, went wrong. We never performed

them together. I think she felt that

Bach or Schumann was more in her style

than an unknown Londoner. Yet the composer’s

name has been at the back of my mind

ever since. A few years later I met

an old church warden in the Lake District.

We were both organists and we chatted

about music and beer and Alfred Wainright.

One thing we had in common was our liking

of so-called ‘light music’. I told him

of my interest in Gilbert & Sullivan

– I had recently been a ‘lord’ in Iolanthe.

He chatted about The Maid

of the Mountains and one or two

other half-remembered operettas. Then

he told me that he had met his wife-to-be

during a performance of The Rebel

Maid. This work is perhaps Montague

Phillips’ best known piece.

The name went to the

back of my mind for a number of years

until Hyperion brought out their wonderful

recording of Joseph Holbrooke’s

Piano Concerto No. 1 ‘The Song of

Gwyn ap Nudd’ Op.52. Naturally,

I avidly read the CD’s learned programme

notes by Lewis Foreman. And there in

the second paragraph something hit my

eye - a list of piano concertos by British

Composers. Some of these I knew - Scott,

Delius and Stanford; but amongst the

many that I had not heard of was one

by Montague Phillips. I happened to

be in the Royal College of Music Library

and looked up the composer in Grove.

There was not much about his life but

a partial list of his works made me

sit up. Here was a catalogue containing

not only one piano concerto but two,

a symphony, various overtures and character

pieces, cantatas and piano works. True,

many of the titles in the list suggested

a ‘light’ or ‘salon’ music tendency

rather than anything weightier. However,

this was not a big issue; as Philip

Scowcroft suggests that there is certain

ambivalence between serious and light.

More thoughts about this later. I remember

looking at the list and shrugging my

shoulders. I would never hear any of

this music; of that I was convinced.

A few years later I

was delighted to buy the White Line

‘British Light Overtures’ CD Volume

3. Amongst many treats on this disc

was Montague Phillips’ Overture: Hampton

Court. It was the first track I

played; I was eager to hear what this

music sounded like. I was delighted

and surprised by this charming work.

We associate ‘things London’ with Eric

Coates, of course. But here was

a composer who was beating the master

at his own game. This music echoes the

feeling of grandeur, history and the

fine gardens at this national treasure.

It is sustained in places and full of

good tunes and sparkling orchestration.

We find, not only a sense of pageantry

but also a curious wistfulness. This

mood makes the overture work for me.

It is a number that would and should

take its place in the active repertoire

of British Light Music. Curiously, perhaps,

it acts as a kind of pendant to the

Surrey Suite Op.59 on the present

disc.

I will not in this

review give an outline of Montague Phillips’

life and works – this has been admirably

done by Philip Scowcroft in his extensive

writing on Light Music on Musicweb.

see SERIOUS

OR LIGHT The

Experience of Montague Phillips by Philip

L. Scowcroft

Symphony in C

minor

Chronologically the

first set of pieces on this disc is

the Symphony in C minor. Unfortunately

this work is not complete. The holograph

was lost in Germany on the outbreak

of the First World War. However the

orchestral parts remained and we are

fortunate that the composer chose to

reconstruct the Scherzo and the

Adagio during the early nineteen-twenties.

These were apparently revised and issued

as two orchestral miniatures – A

Spring Rondo and A Summer Nocturne.

Lewis Foreman notes

that the orchestral parts of the two

outer movements survive – and he suggests

that one day they may be reconstructed.

The Symphony was originally composed

between 1908 and 1911. It was first

performed at a concert in the Queen’s

Hall in May 1912, with the composer

conducting.

What we have here is

a tantalising glimpse of a ‘light’ symphony.

This is escapist music at its very best.

It glories in the kind of suburban atmosphere

in which the composer was living. However,

there should be no disparagement of

this fact. What counts is the artistry

that the composer brings to his materials.

There is no doubt that he is able to

handle the ‘stuff of music’ with consummate

skill.

The Spring Rondo

is in the form of a scherzo and trio.

The opening of this piece is almost

will o’ the wisp. There is considerable

instrumental colour here – Phillips

is well able to balance full orchestra

with passages scored for just a couple

of instruments. Sometimes the music

becomes almost archaic and then the

romantic sensibilities of the time come

to the fore. I would never wish to import

a programme into this music but the

‘Home Counties’ effect seems to spring

to mind. Here we have a composer enjoying

the good things of life; spring in the

Surrey woods perhaps? There certainly

seems to be a gaiety about much of this

music. However, the trio section becomes

a little more wistful; solo violin points

up a more reflective impression. There

is even a hint or two of Elgar in these

pages. The scherzo material returns

and the work ends in a blaze of brass.

The Adagio Sostenuto

or the Summer Nocturne is much

more profound stuff. This perhaps lets

us see the other side of the composer

to that of The Rebel Maid

and the songs. This movement opens with

a great sweeping tune which builds up

to an intense climax. This is a truly

great theme; any composer would be proud

of it. Once again I feel the influence

of Elgar. After the intensity of the

first statement of this idea the composer

shuts down a bit and soon the orchestra

is musing on material seemingly derived

from this opening theme. There is much

use of solo instrumentation. Nevertheless

the intensity is always trying to re-establish

itself. Of course it succeeds for a

while only to collapse back into retrospection.

Soon there is a quiet, meditative passage.

It is scored for three violins and viola.

However the pressure builds up very

quickly – the big tune reasserting itself

and carrying all before it. At times

this sounds deliciously film like. The

last minute is back to reflecting on

the summer’s day; a lovely solo violin

leads to a quiet close.

All in all this is

very tantalising music. I doubt if we

have many ‘light’ symphonies in the

repertoire. I can think of perhaps Eric

Rogers’ Palladium Symphony. However

as far as I know Eric Coates never conceived

a Symphony - although I imagine some

of his suites could almost count as

such. Montague Phillips’ essay in this

form may not be the most profound example

of this genre – however it is well crafted,

well scored and has some beautiful moments.

These two movements must present a strong

case for the restoration of the first

and last.

I love and respect

most of the British Symphony repertoire.

However I can safely say that I would

sometimes rather listen to the Summer

Nocturne than much that passes for

serious musical thought. It is a good

balance between a composer wearing his

heart on his sleeve and a degree of

subtlety that makes this good if not

great music.

Four Dances from

the Rebel Maid

The Rebel Maid

is Montague Phillips’ best known work;

there are still many people around who

have sung in amateur performances of

this operetta. It is a work that I have

never heard, although I have worked

my way through a few of the piano arrangements

of the dances. Although it was composed

during the Great War it was not until

1921 that it was given its first performance

at the London Empire Theatre. It was

not an instant success – perhaps more

to do with the effects of the coal strike;

people were unable to travel into town

for pleasure. The best known song is

the Fishermen of England. It

is interesting to note that the lead

role was written for his wife, the soprano

Clara Butterworth. The composer extracted

this present set of Dances from the

work shortly after the first performance

- they are Jig, Gavotte,

Graceful Dance and the Villagers’

Dance. They are delightful miniatures

in their own right. They have all the

attributes of good light music: good

tunes and contrast between sentimental

and gay moods.

Most important of all,

the scoring has a lightness of touch

that reveals the hand of a considerable

master of orchestration. I suppose my

favourite is the Gavotte – perhaps

because I have known the piano version

of this for many years. However, all

the dances deserve to be aired a bit

more often.

Arabesque Op.43

No.2

The short Arabesque

was the second of Two Pieces

composed as Op. 43 in 1927. The

first is an ‘air de ballet’ entitled

Violetta. Lewis Foreman suggests

that the Arabesque is a pastiche

of romantic Russian ballet music. On

my first listening to this piece I felt

that somehow the balance was wrong.

Yet on approaching it again I see that

it is actually quite a tightly constructed

little miniature. It opens with a theme

that reminds me of something in Roger

Quilter’s ‘Where the Rainbow Ends.’

This is a playful tune that seems to

work its spell throughout the music.

At first it is scored with a light touch

– flutes and oboes in dialogue before

the strings arrive. The woodwind then

engage in a delicate cadenza. After

these musings there is the happy music,

yet this is clearly related to what

has gone before. Soon there are more

overt echoes of the earlier theme and

the music dies away, only to have the

peace broken by a loud last chord. Altogether

a perfect moment of music, which is

very much a child of its time – but

none the worse for that.

A Shakespearean

Scherzo – ‘Titania and her Elvish Court.’

Philip Scowcroft describes

this as a ‘sparkling’ work; no better

adjective could be used. The programme

notes tell us that this work received

its first performance on 31st

July 1934. It is a tone picture of some

of the events from A Midsummer’s

Night Dream. I suppose that my imagery

of this scene is derived from the great

fairy paintings by Sir Joseph Noel Paton;

this music does nothing to destroy this

perception.

There are fairy trumpets

at the beginning of the work, somehow

metamorphosing into the horn of Oberon.

However the Elvish Court soon arrives

on the scene – there is a lot of ‘tripping

hither and tripping thither.’ The music

just bubbles along like a spring stream

in spate. There is much fine instrumentation

here – especially for the woodwind.

It is not quite a moto perpetuo – but

it comes close. About a third of the

way through this dainty theme gives

way to a lovely string tune. For the

rest of the work this tune tries to

reassert itself but never fully succeeds.

There is an interlude where the interplay

of strings and woodwind weave a particularly

magical spell before a little march

takes all before it. Much of this music

has a feel of Tchaikovsky about it;

it would make an excellent ‘scene de

ballet,’ in its own right. The music

ends with considerable excitement; quite

reminiscent of Eric Coates. Altogether

a fine Scherzo that lives up

to its promise to ‘depict’ Titania and

her Elvish Court.

A Surrey Suite

Op.59

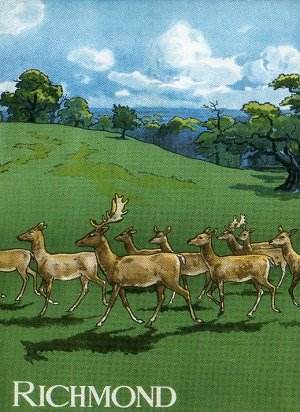

For me this work is

the highlight of the CD. This is not

because it is necessarily the most musical

or because it has any great profound

statements to make about life and existence.

It is simply that this is a musical

portrayal of one of my best loved places

– Surrey and the Royal Park at Richmond.

To my mind this landscape epitomises

much that for me is England; the generally

wooded aspect of this landscape gives

point to this opinion, in spite of the

massive incursion of urban sprawl.

I have many happy memories

of exploring the park and the Surrey

countryside with a very lovely lady.

This music brings to mind happy Saturday

mornings wandering through a sun-dappled

landscape, long views towards Windsor

Castle and the secret vision of St Paul’s

Cathedral through the long ride in the

woods. The Market at Kingston

presents to me the bustle of a half

dozen market towns along the banks of

the Thames – including Richmond, Twickenham,

Teddington and Hampton Court; evenings

of drinking Fullers ‘Chiswick’ beer

by the river.

Montague Phillips lived

in the Surrey town of Esher for many

years, and no doubt spent much time

exploring the surrounding countryside.

The nineteen-thirties was a time of

rapid expansion of the boundaries of

Greater London. It was the time of Greenline

Country Buses. Esher, along with many

other places, was developing from sleepy

market town to dormitory town for the

sleep of commuters to the city. This

was the age of hiking and rambling at

weekends. Tudor style roadhouses and

pubs were the order of the day. Ploughman’s

lunches were devised by the Milk Marketing

Board to sell more cheese.

The music of the Surrey

Suite is presented in three movements:

Richmond Park; The Shadowy

Pines and Kingston Market.

It is perhaps wrong of Lewis Foreman

to suggest in his programme notes that

‘the Surrey that Phillips knew was not

choked with cars and over-development

as it is now...’ As noted above, by

the time this Suite was composed, much

of what we regard as urban sprawl was

well on the way; there were some three

million cars on the road and bypasses

and dual carriage-ways were becoming

common. What Phillips is doing is what

we all do from time to time. He was

re-creating musically an image or a

picture of what he felt Surrey used

to be like – or more appositely what

he would like it to be like. Nearly

seventy years on, the Surrey I think

of or walk hand in hand down a country

lane at Shere, is much the same as depicted

here by Phillips. It is as much a creation

of the mind as a description of an actual

landscape.

The first movement

opens with a walk or perhaps a canter

through the park. This is fine music

that is lightly and subtly scored. The

main tune is sequential in an almost

Handelian manner. Who could not be happy

listening to this music? Who would not

want to be tramping across the grass

looking at the herd of deer and at St

Paul’s on the horizon? There follows

a slightly more melancholic tune – almost

Sullivan-esque in its demeanour. This

leads to an intense passage before returning

to the canter and close.

The Shadowy Pines

is a beautiful reflective piece. It

has an interesting and inspiring tune

for the main thematic material. The

composer quite obviously wears his heart

on his sleeve – but so what. This is

the loveliest moment on this CD. There

is a big climax which the composer closes

down into a gorgeous meditation for

solo violin. The movement finishes pianissimo.

The opening to the

third and last movement reminds me of

Benjamin Frankel’s well known Carriage

and Pair. This is a jaunt through

the town centre – probably in an open

top tourer rather than a chaise! There

is all the bustle we would expect of

a vibrant market town – although the

music makes room for a quiet pint in

a pub by the riverside. The brass scoring

is first-rate and the work finishes

with a good downward woodwind swirl.

Moorland Idyll

Op.61

This short Larghetto

was composed in 1936 for an ensemble

made up of members of the BBC Symphony

Orchestra. Lewis Foreman points out

that the whereabouts of the ‘moorland’

is not known; there are few clues in

the music. However it is fair to say

what moorland it is not. There is none

of the bleakness of Holst’s Egdon

Heath; this is not a millstone grit

Lancashire landscape or Wuthering Heights.

Neither is it the softer heather-clad

slopes of Delius’s North Country

Sketches.

The landscape is not

wild – there is a country pub or a church

nearby. Perhaps it is the South Downs

or Chanctonbury Ring with views to the

sea. This is a sunlit landscape – there

are flowers and butterflies, not a Ted

Hughes’ desolation. However this music

is not impressionistic; it is not descriptive.

It is actually quite ‘film-like’ in

its structure and texture. Good light

music.

Revelry Overture

Op.62

Lewis Foreman in his

programme notes suggests that this piece

is the epitome of light music of its

time. He feels that it sounds so entirely

familiar that it must have been used

as an erstwhile BBC signature tune.

This is, he feels, how he first came

across this piece, however, he has been

unable to identify which programme it

was.

The music commences

as it means to go on – with a sparkling

curtain raiser. This is quickly followed

by a forward-moving tune. There is little

let-up in the general mood of this music

although I feel that there are one or

two weak points in the ‘middle eight’

where the inspiration seems to run dry.

However all is forgiven as the ‘well

known’ tune returns in all its glory.

This is decidedly happy

music. Here are none of the concerns

that were haunting other writers and

composers at this time. We do not find

reference to the rise of Nazism here

or the horrors of the Spanish Civil

War. The only reference to the current

political situation appears to be the

use of castanets!

This is pure escapism

and when we accept that this is the

case we can put weightier matter to

one side and take sheer pleasure in

a ‘damn good tune.’

I agree with Lewis

Foreman that this music sounds so unbelievably

familiar – especially the big tune.

Perhaps it is just a case that it is

an unconscious parody of all that is

best in light music melody construction.

It was first performed on New Years

Eve 1937.

Sinfonietta in

C Op.70

This work is the most

substantial on this CD. Of course the

Symphony would hold this honour when

and if the two outer movements are reconstructed.

The Sinfonietta was composed

in 1943 in the middle of the Second

World War. Lewis Foreman points out

that this work is ‘innocent and lacking

angst’. With this statement I partly

agree. True there are no tensions comparable

to say, Vaughan Williams’ Fourth

Symphony. However what I feel the

composer is doing is reflecting back

to quieter times (whenever they occurred)

and is perhaps looking forward to peace

in the future. Maybe this is reading

too much into what is basically a warm-hearted

and lyrical work. However there is a

certain wistfulness and longing here

which is perhaps not evident in some

of the other works essayed in the CD.

It is in this work

that Montague Phillips comes closest

to the mainstream British music of the

period. Of course he is no Britten or

Berkeley, but this work is far removed

from the Shakespearean Scherzo

written nearly a decade previously.

There is less here of the music of Eric

Coates and Haydn Wood and perhaps more

of the Forties film score type of tune.

Some of this music exhibits a depth

rarely associated with ‘light’ music.

The first movement

gets off to a good fanfaring start.

The tempo is Allegro risoluto. However

there are many tender and reflective

moments here. There is a lovely lyrical

moment pointed up with a solo oboe.

There are even some passages in the

‘development’ section that look forward

to the music of Malcolm Arnold.

The slow movement is

quite exquisite. The opening passage

is scored for oboe solo accompanied

by the harp. This music develops very

slowly with an almost Elgarian longing.

The oboe returns again to comment on

the more romantic string tone. The only

problem is that this movement is too

short. It seems like no time at until

the violin is reprising the theme quietly

to itself. Soon the movement dies away

into a dreamy silence.

The last movement is

a romp. It is entitled a Scherzo – and

this is entirely appropriate. We hear

the orchestra playing some interesting

rhythms of a kind not heard in this

disc so far. The contrast between sections

of this piece is effective. The sleeve-notes

describe the second theme as ‘perky’

and this is correct. After a brief climax

the music takes a march-like character.

There is nothing of the Crown Imperials

here though; it is a quietly sustained

effort that leads us back to the opening

music. Once again we aware of some very

interesting orchestral effects – for

muted brass and percussion. The work

ends with a nice brassy peroration.

This CD represents

an ideal introduction to the music of

Montague Phillips. In fact it is the

only recording (apart from the Hampton

Court Overture mentioned above)

which allows us to make an evaluation

of this competent, imaginative and largely

forgotten composer.

Philip Scowcroft is

right in pointing out the ambivalence

that exists between the ‘lighter’ and

the more ‘serious’ sides of Montague

Phillips. Apparently the obituarist

of the Times noted him as a composer

in the ‘light’ tradition

The truth about Phillips

is probably a bit more subtle, as these

recording shows. He was of the opinion

that there was a place for ‘light’ music

for the ‘great majority of people who

lie between the ultra high-brows and

the irredeemable low-brows and who can

appreciate music that is melodious and

well written but not too advanced.’

However I am of the opinion that this

statement is not quite as simple as

it appears. I can quite happily cross

the boundary between so called ‘high’

and ‘low’ brow music – and I am sure

many people can. I find that some days

I want be involved with some complex

organ music by Olivier Messiaen or Bartók

string quartets. Other days I am quite

content to listen to Glen Miller’s Chattanooga

Choo-cho, Tales of a Topographic

Ocean by Yes or She Loves You!

Are these ‘high’ or ‘low’ brow?

What I do find about

music like that of Montague Phillips

is that it evokes a feeling of well-being

– it does not challenge my political

or religious sensibilities like say,

Tippett’s Child of our Time.

It allows me to indulge myself in my

innocence – to a time when life seemed

simpler and free from the ambiguities

of the present. Whether this is true

or not is academic.

Montague Phillips has

given us a corpus of music which is

extremely well written, it is tuneful,

it is interesting and evocative of past

times. It is self indulgent music and

as such it is as necessary to our well

being as treacle steam pudding and custard.

I thank my lucky stars that I can take

music like this off my shelf and sit

back and imagine myself tramping across

Box Hill or exploring the hidden corners

of Richmond Park. And what is more to

the point I can imagine all this without

the guilt that I should be applying

a more rigorous critical appreciation

to the music in hand.

I recommend this disc

to all lovers of English music and to

all those who love music that is tuneful,

well composed and thoroughly enjoyable.

The sound quality and the playing is

of course excellent. The sleeve notes

are essential and the cover picture

is so evocative at to bring a tear to

the eye.

I hope that this issue

proves to be popular and that Dutton

or some other enterprising recording

company will issue one or other or both

of the two Piano Concertos.

John France

a further review from Stephen

Lloyd

In the days when light

music was taken seriously and given

regular slots in BBC radio programmes,

Montague Phillips was a familiar name.

This was especially the case during

the BBC Concert Orchestra’s ten years

under Vilem Tausky (who died in March)

who was a friend of the composer. Yet,

amazingly, none of his works seems to

have been recorded on LP. Only the overture

Hampton Court has recently become

available on CD (British Light Overtures

Vol. 3 CDWHL2140). Marco Polo has so

far by-passed Montague Phillips in its

British Light Music series, so this

CD devoted entirely to his music is

greatly to be welcomed, with Dutton

in what might otherwise be regarded

as ASV White Line territory!

Montague Phillips was

born in Tottenham in 1885 and died at

Esher in 1969. From 1901 to 1905 he

studied at the Royal Academy of Music

where Frederick Corder was his professor

of composition. At the RAM he proved

himself a student of much ability, gaining

both Smart and Macfarren Scholarships,

as well as the Charles Lucas medal for

a Symphonic Scherzo. He was organist

and choirmaster at Wanstead in 1904

and at Esher in 1908, a post he was

to hold for 35 years. During the First

War he served in the RNVR and a posting

to Scotland, where he was stationed

with librettist Gerald Dodson, led to

collaboration over the light opera The

Rebel Maid for which he became best

known. Based on a book by Alexander

Thompson and with lyrics by Dodson it

was first staged at the Empire Theatre,

Leicester Square in March 1921 where

it ran for 114 performances. His wife,

Clara Butterworth for whom he also wrote

many songs, took the leading role, recording

four of them for Columbia. Another,

The Fishermen of England, became

a popular success. In 1926 he was appointed

professor of composition at the RAM.

Although Montague Phillips

composed a symphony, two piano concertos

(the second was revived in 1989 by Robert

Tucker at one of his annual Eton concerts),

a Phantasy for violin and orchestra,

and a few choral works, he gained greater

success with his songs, of which over

150 were published, and with his light

orchestral pieces which he frequently

conducted in broadcasts and with municipal

orchestras. Nature titles such as Forest

Idyll, A Hillside Melody, A Forest

Melody, Hampton Court,

In May-time, Dance Revels,

Three Country Pictures, Village

Sketches and The World in the

Open Air (the last five being suites)

suggest works of charm, freshness and

innocence – which is just what they

are. Montague Phillips’ music is distinguished

by a broad, almost Elgarian melodic

line, a lively pulse, and fresh orchestration,

nearer in style to Haydn Wood than Eric

Coates. It also has a rich vein of melancholy,

best exemplified by the long eloquent

tunes that open A Summer Nocturne

and The Shadowy Pines, the second

movement of A Surrey Suite.

This CD offers an excellent

selection, including A Surrey Suite

with its evocative titles Richmond

Park, The Shadowy Pines and

Kingston Market; this reviewer’s

personal favourite from much replaying

of a 1965 broadcast under Tausky (and

later ones: in 1976 conducted by Eric

Wetherell and another by Tausky in 1984).

It comes up freshly minted in a convincing

performance with Gavin Sutherland conducting

the BBC Concert Orchestra. Also from

Tausky days we have the Overture Revelry,

Moorland Idyll and the spirited

Shakespearean Scherzo ‘Titania and

her Elvish Court’ in which one should

forget Bottom and focus instead on Titania’s

quarrel with Oberon.

The earliest pieces

are two movements from the Symphony

in C minor that the composer himself

conducted at the Queen’s Hall in an

all-Phillips concert with the London

Symphony Orchestra in May 1912. It was

received favourably by the Times

critic, but with one suggestion: ‘One

wonders whether the composer will not

come eventually to the conclusion that

some pruning will be necessary, especially

in the first movement, and whether he

will not feel that his music requires

longer periods free from climax. Each

of these is somewhat in the same style,

a sweep up the gamut to a crash followed

by comparative peace or absolute silence,

and they come very often, and in all

the movements. They are so well managed,

however, and so exciting to listen to,

that the ear does not weary of them

at a first hearing at all; but one doubts

whether they will stand the test of

repetition and of time.’ Events made

Phillips carry out the suggested pruning

when, as Lewis Foreman tells us in his

informative note, the symphony suffered

a fate similar to Vaughan Williams’

A London Symphony in that the

full score was lost in Germany, its

composer having to reconstruct it from

the orchestral parts – or at least the

second and third movements which became

the Spring Rondo and Summer

Nocturne on this CD. It was, perhaps,

a happy consequence as ‘symphony’ is

too formal a title with which to yolk

these attractive yet by no means lightweight

pieces. (The Times review, incidentally,

seems to suggest that the slow movement

originally preceded the ‘scherzo and

trio’.) One probably has to go back

to 1966 for the last performance and

broadcast of these movements, again

under Tausky.

The Four Dances from

The Rebel Maid, as with any orchestral

extracts from show music, work better

for those who know the operetta. The

Jig is the orchestral introduction to

Act III; the charming pastiche Gavotte

is the dance that directly follows the

Act I vocal quartet Shepherdess and

Beau Brocade, the Graceful Dance

leads on from Abigail’s Act II song

I want my man to be a landlord,

while the last dance chronologically

comes after the Act III introduction,

though here without chorus. Although

very much of its time, The Rebel

Maid is a finer operetta than these

dance extracts on their own may suggest

and is worthy of reviving by some amateur

operatic company. Set in 1688, the story

concerns the invasion of the Prince

of Orange at Torbay and abounds with

plots, disguises, treachery and love.

The libretto may creak but this is overcome

by the music which contains many fine

numbers, most notably those written

with Clara Butterworth in mind. In 1966

Vilem Tausky broadcast a substantial

selection that certainly whetted this

reviewer’s appetite.

The latest work here

– and the last on the disc - is a BBC

commission, the Sinfonietta in C, which

Phillips premièred in September

1943. In the first movement we find

him quickly shaking off the shackles

of the work’s formal title as he leads

into one of his broad tuneful melodies.

The wistful mood of the middle movement

makes one feel that some nature title

would have sufficed, and if the boisterous

last movement is marginally less satisfactory,

interest is at least maintained by the

rhythmic variation of its themes and

the contrast of moods. A delicate Arabesque

completes the roll-call of works. There

are no duds here. For anyone who enjoys

tunes with a dose of nostalgia, this

is definitely a disc to have. So switch

on the BBC Light Programme or the Home

Service, sit back and relax ...

Stephen Lloyd

Montague Fawcett

Phillips (1885 1969)

List of Key Works

| |

Stage Works

|

|

|

The Rebel Maid

|

|

1921

|

|

The Golden Triangle

|

|

1921?

|

| |

|

|

| |

Orchestral

|

|

|

Boadicea: Overture

|

|

1907

|

|

First Piano Concerto

|

|

1907

|

|

Symphony in C minor

|

|

1911 (rev 1925/25)

|

|

Phantasy for Violin &

Orchestra

|

|

1912

|

|

Heroic Overture

|

|

1914

|

|

Second Piano Concerto

|

|

1919

|

|

In Maytime

|

|

1923

|

|

A Hillside Melody

|

|

1924 (rev 1946)

|

|

Dance Revels

|

|

1927

|

|

Violetta, Air de Ballet

(arr.)

|

|

1927

|

|

Arabesque (arr.)

|

|

1927

|

|

A Forest Melody

|

|

1929

|

|

Three Country Pictures

|

|

1930

|

|

Village Sketches

|

|

1932

|

|

The World in the Open

|

|

1933

|

|

A Surrey Suite

|

|

1936

|

|

A Moorland Idyll

|

|

1936

|

|

Revelry Overture

|

|

1937

|

|

Empire March

|

|

1941

|

|

Sinfonietta

|

|

1943

|

|

Festival Overture

|

|

1944

|

|

Hampton Court Overture

|

|

1954

|

| |

|

|

| |

Piano

|

|

|

Berceuse

|

|

1910

|

|

Nocturne

|

|

1910

|

|

Violetta, Air de Ballet

|

|

1926

|

|

Arabesque

|

|

1927

|

|

Jacotte

|

|

1928

|

| |

|

|

| |

Chorus & Orchestra

|

|

|

The Death of Admiral Blake

|

|

1913

|

| |

|

|

| |

Voice & Orchestra

|

|

|

The Song of Rosamund

|

|

1922

|

| |

|

|

| |

Voice & Piano

|

|

|

Dream Songs

|

|

1912

|

|

Sea Echoes

|

|

1912

|

|

Calendar of Song

|

|

1913

|

|

The Fairy Garden

|

|

1914

|

|

Flowering Trees

|

|

1919

|

|

From a Lattice Window

|

|

1920

|

|

Old World Dance Songs

|

|

1923

|

see

also Volume 2