COMPARISON

(same program): Perahia/Abbado – Sony Classics 64577 [57:20]

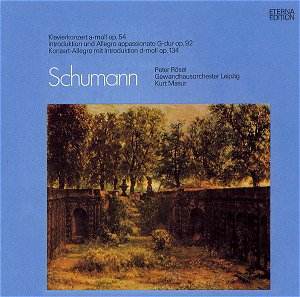

Kurt Masur is one of our most well known conductors

of the central symphonic repertoire but Peter Rösel is a

hidden treasure who spent most of his productive years behind

‘The Berlin Wall’. In recent years, Berlin Classics has issued

many of his recordings. Although they have uniformly received

excellent reviews, Rösel remains a pianist who is rarely

mentioned in the same sentence as a Perahia or Goode. If memory

serves me correctly, my first exposure to Rösel was an EMI

disc of the Weber Piano Concertos (now on Brilliant Classics)

played in excellent fashion. Every other Rösel disc since

that time has received many hours of play on my home audio systems.

More often than not, recordings of Schumann’s

famous A minor Piano Concerto are coupled with a major Schumann

solo work or another famous concerto such as the Grieg Piano Concerto,

also in the key of A minor. Rösel and Masur deviate from

the norm in programming the two piano-with-orchestra works from

Schumann’s later years. As it happens, I have a disc from Murray

Perahia and Claudio Abbado with the same program, and I used this

recording extensively in the review process.

Schumann’s Concerto has a piecemeal history.

In 1841, he wrote a one-movement Fantasy that no publisher would

touch. The advice he received was to add two movements to make

the work into a concerto. Schumann evidently didn’t take immediately

to the advice, because it took him four years finally to add the

two movements. Further, it is ironic that the last thing he did

with his Concerto was to add a transition between the 2nd

and 3rd Movements, this transition being one of the

most famous in all classical works.

The piecemeal history would tend to indicate

that Schumann’s Concerto would not have a strong level of coherence.

However, Schumann overcame that possibility by using, in different

guises, the A minor primary theme of the 1st Movement

throughout the work. Thus, the A minor Concerto is essentially

monothematic and has raised some complaints from listeners that

Schumann’s wealth of creativity in the Concerto is rather low

and that the composition is too long. A different line of thought

is that Schumann masterfully varied the A minor theme to the extent

that most listeners would not be aware of its monothematic elements.

Personally, I consider the 1st Movement too extended,

but the other two movements possess perfect length.

Comparing the Perahia and Rösel recordings

of the Piano Concerto brings into view a basic difference in presenting

stereo sound. Perahia’s soundstage is the typically modern one

of very small spacing between instruments that leads to a homogenized

sound where distinctions among voices decrease. I won’t deny that

it sounds attractive, but at the loss of detail. Particularly

in the 3rd Movement, Perahia’s projection has trouble

gaining distinction above the orchestra.

With Rösel’s recording, the stage is much

wider. When the time strikes for Rosel to ascend, his soundstage

is fully agreeable. Rösel takes full advantage, giving a

performance that rivals the outstanding performance of Jorge Bolet

on Decca conducted by Riccardo Chailly. His exuberance is boundless,

and he weaves his way through the orchestral tapestry of the 3rd

Movement with distinction and a great rhythmic pulse. He also

does very well with the poignancy of the 1st Movement,

although Perahia’s inflections are more incisive. Both conductors

are excellent in keeping the music interesting and uplifting,

although Abbado takes a more cultured path while Masur conveys

a rustic atmosphere. Overall, I find the Rösel version compelling;

Perahia is enjoyable.

Although Schumann’s later two works for piano

and orchestra do not scale the heights of the A minor, they are

worthy of a fine interpretation. Perahia’s versions are smooth

and rather serene, because Abbado fails to create significant

tension. Yes, his orchestra can be quite loud and make grand gestures,

but the lack of tension means lack of urgency. Masur gives us

hard-hitting performances recognizing that Schumann wasn’t a has-been

in his later works and that his inner world retained elements

of desperation. Abbado conveys a man who has lost ‘the edge’;

by doing so, Florestan also becomes more benign.

The 3-minute time differential between the two

discs is of little significance. To be honest, I only noticed

a difference in tempo with the Intermezzo to the Piano Concerto,

and Rösel was the quicker and more refreshing pianist.

In summary, I heartily recommend the Rösel

disc for its idiomatic performances. The 3rd Movement

of the Piano Concerto is one of the best on record, and the two

later works are also very impressive. The sound quality is lacking

richness, but I am well satisfied with the expansive and crisp

soundstage. As for the Perahia recording, the sound integration

and Abbado’s somewhat limp portrayal of Florestan in the later

works are problematic features that give the disc a low priority.

However, those who place highest attention on the beauty and grace

of Schumann’s music will certainly have a more favorable opinion

of the performances than I possess.

Don Satz