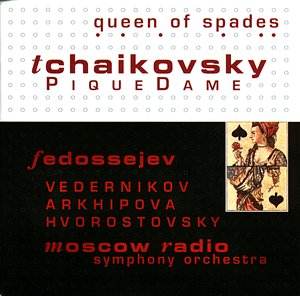

Outside Russia, and certainly in the UK, productions

of operas by Tchaikovsky are often limited to the lyrical Eugene

Onegin, and, by some distance, the more dramatic Pique Dame -

his penultimate work in this genre. Both works are based on poems

by Pushkin. The present set is unique in presenting read extracts

from the poem interspersed by arias from the opera.

Pique Dame tells the story of the fated love

of a young officer, Hermann, for Lisa, grand-daughter of the Countess,

a renowned gambler, and who is believed to hold the secret of

the three cards. Lisa is betrothed to Prince Yeletsky. Hermann

believes he lacks the money to displace Yeletsky and that the

only way to obtain it is by winning at cards. To succeed he needs

the Countess’s secret. She dies of shock as he seeks it from her.

However, she returns as a ghost and reveals the satanically influenced

secret to him as ‘three seven and ace’. She also encourages him

to marry Lisa. Hermann gambles all against Yeletsky, but the third

card is the Queen of Spades and the Countess’s apparition appears

to him again as he stabs himself. The devilish pact is fulfilled.

On record Pique Dame has had a mixed history,

with theoretically ideal casts being marred by recording quality

or the odd flawed soloist. That changed with Gergiev’s 1992 recording,

where the conductor’s dynamism and feel for the idiom is allied

with an excellent team of soloists. It immediately became a clear

first choice (Philips). That issue shared with the present set

the veteran Irina Arkhipova, as the Countess. Hers is a portrayal

that reeks of experience. Her full tone, excellent diction and

phrasing are allied to well held legato. This she can mobilise

at very slow speed, in her great aria (CD2 Tr.5), and where she

slips imperceptibly from Russian into French. Natalia Datsko takes

the role of her grand-daughter, Lisa. Datsko’s full-toned voice

is more dramatic than lyric and is even throughout its wide range.

Her palette of vocal colour is well used in expressing Lisa’s

many emotions (CD2 tr.9). A particular pleasure is her duet with

the mellifluous-toned mezzo of Nina Romanova as Pauline (CD1 trs.8-9).

Lisa’s betrothed, Yeletsky, is portrayed by Dmitri

Hvorostovsky who also sang the part in Ozawa’s flawed recording

for RCA. His singing is outstandingly expressive, secure throughout

the range, and allied to full fresh even tone. It is a formidable

portrayal. Good as Chernov is for Gergiev, Hvorostovsky is better.

His rendition of Yeletsky’s Act 2 aria, in which he states his

love for Lisa (CD2 tr.1), is justifiably treated to enthusiastic

applause. Hvorostovsky is well matched for vocal strength by the

Hermann of Vitaly Tarashchenko. His typical Slavic tenor has baritonal

overtones and a slightly husky quality. However it is a true tenor

voice with plenty of heft for the dramatic outbursts. He is, however,

able to lighten his tone to lyric tenderness as he pours out his

love to Lisa (CD1 tr.11). Equally well thought and expressed are

his use of phrasing and tone as he meets the Countess (CD2 tr.6)

and later as he reads Lisa’s forgiveness.

The minor solo parts are all sung convincingly

and with good tone; not a Slavic wobble within sight or, more

relevant, hearing. Most impressive too is the vibrant chorus,

even more so the orchestral playing under Vladimir Fedoseyev,

their long time conductor. He draws fine playing and conveys the

episodic drama superbly. Although denoted ADD the recording is

full and clear with an excellent balance. The occasional instances

of applause, all well deserved, are not unduly extensive or intrusive.

The ‘bonus’ of the reading of extracts from Pushkin’s

poem, interspersed with arias from the opera, will mainly be of

interest to Russian speakers and those spotting names for the

next generation of singers from Russia. The booklet has the text

of the opera in Cyrillic and ‘Roman’ form with a translation in

English. The artist profiles are given in Russian and English

but are shy on dates of birth. There are plenty of spelling errors

in the English translation. The track listings would have benefited

from English translation and reference to a numbered page in the

libretto, the pages of which are not numbered.

Caught with the tension of a live performance,

but without the disadvantage of stage movement, this well sung

and played idiomatic performance is a worthy addition to the catalogue.

It also has the benefit of Hvorostovsky’s Yeletsky, caught at

the peak of form a few months after he won the accolade of ‘Cardiff

Singer of the World’. It can stand alongside, or compete with,

Gergiev’s well cast and conducted studio recording.

Robert J Farr