Strauss

was not averse to making himself the subject of his own works,

for example as a hero in Ein Heldenleben, a lover in Intermezzo

and a father figure in Sinfonia Domestica, which he

dedicated to his ‘dear wife and children’. That he pursued this

lavish self-promotion through thrilling melodies and brilliant

orchestration does not alter the fact that the ‘plot’ is not particularly

interesting; so why not relax and let this voluptuous music wash

over you? This could be a reasonable alternative to trying to

sort out the domestic squabbles, splendours and miseries of the

Strauss family while listening. Papa might occasionally sound

like a self-obsessed old windbag, but he’s never boring.

It

seems almost as though both these works were allowed to evolve

in an improvisatory way; yet Strauss’s mastery of form and dramatic

incident is evident throughout. Nothing happens by chance, and

through all five movements of the Sinfonia the rich fabric

is embroidered with colourful threads and thrilling highlights.

As in Ein Heldenleben, there are quotations, and near-quotations,

from other Strauss works; yet, though Sinfonia Domestica

might appear an obvious example of programme music, it possesses

relatively few of the deft programmatic touches that make Til

Eulenspiegel and Don Juan masterpieces of musical scene

painting.

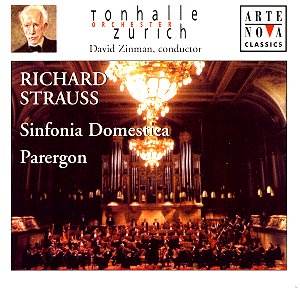

Zinman’s

approach is refreshing, highlighting the invention and vivacity

that pervades this unusual work. The well-upholstered sound that

has long characterised Strauss performances by most of today’s

European orchestras is replaced by a clean, clear interpretation

with a by no means leisurely beat that neatly evades pomposity.

Strauss

added a further ‘chapter’ to his story in Parergon, written

a year later for piano (left hand) and dedicated to the pianist

Paul Wittgenstein (1887-1961) who had lost his right arm in the

war of 1914-18. It contains five interconnected sections, and

is described in the insert booklet as ‘a symphonic virtuoso piano.piece’.

Parergon has been said to reflect Strauss’s undefined anxieties

about his own son. Once again these subjective allusions need

not unduly bother the listener. The work is markedly different

in scale and size from the Sinfonia, tonal and academic

in character, it does not lack interest and its inclusion on this

disc is justified, if only on the grounds of completeness. But,

though excellently performed, in my view it does not make a satisfactory

link to the Sinfonia and it is easier to regard it as a

separate work.

Roy

Brewer