Handel

wrote 'Solomon' after a group of martial oratorios to texts by

the Revd. Thomas Morrell. Morrell's libretti all helped Handel

to mine the national mood in the wake of the 1745 Jacobite uprising

and Cumberland's subsequent victory. But Morrell's rather broad-brush

libretti restricted the scope of Handel's writing. For his next

pair of oratorios ('Solomon' and 'Susanna') Handel turned to another,

anonymous librettist. It is one of the curiosities of Handel's

life that despite the not inconsiderable documentation for some

areas of his career, there are glaring lacunae such as this.

The

librettist for 'Solomon' may have been Newburgh Hamilton who did

the necessary alterations to the original texts on which were

based 'Alexander's Feast' and 'Semele'. The libretti for 'Solomon'

and 'Susanna' have much in common, particularly their use of descriptions

of Nature and the Natural world. Handel was quite susceptible

to such sentiments and produced some highly evocative music in

both the works. Morell's libretti tended to be rather full of

pious platitudes and abstract ideas. So it is not surprising that

given the libretto to 'Solomon', Handel gives us a wonderfully

rich piece with double choruses and a remarkably large orchestra

(Strings, flutes, oboes, bassoons, horns, trumpets and timpani).

Though he uses his orchestra with remarkable restraint, the trumpets

and drums not performing until the opening of Act II.

'Solomon'

is based on II Chronicles and I Kings together with a few hints

from Josephus's Antiquities of the Jews and is essentially an

undramatic piece. In Act I, Solomon and Zadok, the High Priest

celebrate the completion of the Temple. Solomon goes on to consummate

his marriage with Pharaoh's daughter. This later section is remarkable

for the explicitness with which it hymns the joys of the marriage

bed (Something that may have led Handel to drop this act entirely

when he revived the piece later on in his career). Act II deals

with the story of Solomon's judgement of the case of the two harlots,

each one laying claim to a baby. This is the only dramatic section

in the oratorio. Act III starts with the famous Arrival of the

Queen of Sheba and the remainder of the act details her visit

and Solomon's entertainment for her. 'Solomon' may have had an

underlying narrative in glorifying the Augustan Age of George

II, but given that we have little basic knowledge about the genesis

of the oratorio, such ideas must remain suppositions. What the

piece does do though, is give us a picture of a golden age, picturing

its religion, the bliss of happy marriage, justice, noble buildings

and lovely countryside along with the envy of neighbouring states.

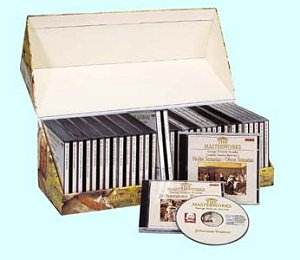

The

previous volume in this series, 'Judas Maccabaeus', was also recorded

by the Amor Artis Chorale and the English Chamber Orchestra under

Johannes Somary. In that volume the performance of the Amor Artis

Chorale was disappointing but they did rise to the challenge of

the martial nature of that work. In 'Solomon' their robust vibrato

laden tones are generally unsuitable for Handel's sophisticated

choral writing. The opaque sound of their singing is unsatisfactory

in such pieces as the Nightingale chorus.

As

with 'Judas Maccabaeus' the soloists provide some consolation.

Sheila Armstrong is by turns ravishing, appealing and charming

as the three heroines (Pharaoh's daughter, the first Harlot and

the Queen of Sheba). Her scenes with Felicity Palmer's vehement

second Harlot are dramatically memorable. Unfortunately these

scenes, as with much else in the set, are marred by the Solomon

of Justino Diaz.

Handel

almost certainly viewed Solomon principally as a lover, after

all there is no martial element in the opera. And in the oratorios,

as in the operas, lovers were almost certainly high voices. It

is unlikely that he was constrained by available personnel, after

all if he had wanted Solomon to be a low voice then he could simply

have allocated the alto to one of the priestly roles, something

he did in other oratorios. Solomon was originally sung by a female

contralto, but on recent recordings the role has most successfully

been sung by both female and male altos. Unfortunately, on this

recording the role is sung by a bass. Diaz has a very dark voice,

which renders Solomon even less youthful than would have been

the case with a lighter voiced baritone. His English is admirable

but, coupled with the illogical tessitura, the slight accent unfortunately

becomes just another thing to get annoyed about. Singing solo

he makes a decent stylist, it is just a pity that he was not singing

a real bass part. But in the ensembles the octave transposition

falsifies the relationships between the voices and violates the

delicate balance of Handel's orchestration.

As

Zadok, Robert Tear is in bright, fearless form. In the passage

work, I think he was probably attempting to give the notes a little

more weight, commensurate with the nature of the general performance.

Unfortunately this misguided attempt results in passage work that

too often sounds like a car starting. This is a shame as Tear

is a fine performer and this mars what could have been a good

performance. As a Levite Michael Rippon performs decently, but

occasionally sounds uncomfortable.

The

English Chamber Orchestra turn in another stylish performance.

A little heavy by today's standards, but the orchestral contribution

remains one of the most listenable parts of this recording. Somary's

speeds remain on the steady side without ever getting too heavy.

Robert

Hugill