Why put opera on DVD? The most obvious reason

is that opera is a visual as well as an aural art form, and seeing

the action on the stage produces a more total experience than

merely listening to the soundtrack. This is logical enough, but

really answers the question "Why watch opera?" rather

than the more specific "Why record opera?" that

is implied in the opening question. On a purely theoretical level,

the arguments for recording opera on film must revolve around

what film can give that the live experience cannot. The most obvious

advantage here is the ability to view in the comfort of one's

own home, as frequently as one wishes. It is this issue of frequency

that this writer feels is the core of the problem with a number

of opera DVD releases currently available, including this Rinaldo.

In the live situation the theatrical element, that aspect of being

actually in the theatre and therefore having an immediate

acceptance of the conventions (both traditional and modern) of

theatrical practice, is paramount. In the situation of viewing

a recording of the live theatrical situation the parameters

are changed and the acceptance of some of the more contemporary

theatrical conventions is harder to deal with.

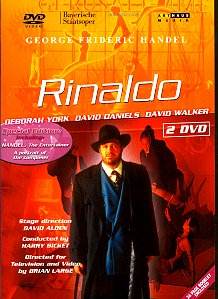

In the context of this particular release of

a performance from the Prinzregententheater in Munich from the

2001 season it is the difficulty of transferring the conventions

of the live theatre into the situation of the repeatedly available

recording that let this DVD down. The problems are on both the

musical level and the theatrical level. To deal with the latter

first; it is currently the convention in the staging of baroque

opera to seek historical accuracy in the musical aspects but to

juxtapose this with modernity of staging, setting and costume.

The live situation allows a degree of acceptance of this, because

the synopsis in the programme will usually outline the director’s

reasons for changes made to place and time of the action. In this

DVD the booklet (which announces itself as being of "36 pages"

but of which only 6 are actually notes in any one language) makes

numerous references to the spectacular effects of the original

performance in 1711, all of which sound great fun. Clearly it

was an extravagant and lavish production. The booklet further

explains that, in the current production, the director, David

Alden, has made "the characters move in an ironic blend of

Twenties look, trendy club scene and ‘sacro’ kitsch." What

neither the booklet nor the production seem to be able to explain

is "Why?" Almirena (Goffredo’s daughter and Rinaldo’s

fiancé) sings the famous aria Lascia ch’io pianga

"suspended like a paralysed mermaid in a neon-blue water

tank." Why? The twenties look seems to involve all the male

cast wearing long overcoats and wide-brimmed homburg hats – very

much more a forties look really – with the exception of Argante,

the King of Jerusalem, who wears a voluminous Turkish dressing-gown,

big floppy Sultan pants a headband like an Egyptian Pharaoh. Why?

The sets seem to be largely imitations of an ugly hotel foyer

circa 1970, with the addition of many different-coloured

hands, each containing an eye, painted on the walls. It is a peculiar

mish-mash of images, without apparent purpose.

To return to the earlier distinction between

live and recorded situations, there are things that the live audience,

caught up in the overall ambience of the production, will accept

at face value. However, the viewer of the recording gets an impression

of unanswered questions piling up each time the disc is viewed.

The more it is viewed the more confusing it seems to become. Goffredo

is a general. So why does he look like a teenaged insurance salesman

with a pigtail? Rinaldo is a great military hero. So why does

he look like an accountant? Furthermore, there are clearly aspects

that the audience in the auditorium will accept, which the television

viewer with close-up photography, mostly from the stage itself,

cannot. No matter how beautifully Deborah York sings her Almirena

(and it is beautiful) she is clearly 20 years older than David

Walker’s Goffredo, her father. From the auditorium she may look

like she is in a tank of blue water, but from three feet away

she very clearly is not. And while Argante moves around her tank

we see little of Argante and a lot of the florescent light-tube

providing the lighting for the tank. It does not take much nouse

to notice that the sets were designed to be seen from afar, not

from the stage. So why are the cameras on the stage?

On to the musical aspects. The big draw-card

on this disc must be David Daniels. Handel could have written

his arias for Daniels, so perfect is his voice. Shut your eyes

and let it wash over you. He is as superb as his reputation suggests.

The only trouble is that the listener does not really want to

see how much the poor fellow sweats spending a more-than-two-hour

opera under the stage lights wearing a shirt, tie, suit, heavy

woollen overcoat and hat. Deborah York, as mentioned above is

in fine voice, though not well cast as the youthful daughter of

Goffredo. It may not have been possible to make York look much

younger, but then, would it not have been obvious to make David

Walker’s Goffredo look older? It can’t be that hard. And on David

Walker, we come to the real musical problem. He just cannot sing

in tune. The whole performance he remains microtonally flat on

every important note. It is not a new habit. He was a disastrous

Nero in Monteverdi’s L’Incoronazione di Poppea at English

National Opera a few years ago, for the same reason. In close

proximity to David Daniels the shortcomings of David Walker’s

countertenor are thrown into sharp relief and it is not pleasant.

On the other hand, what Harry Bicket has achieved with the Bavarian

State Orchestra is very fine. They are a great orchestra, but

not the first group that would spring to mind for ideal orchestral

Handel. However, there is nothing old-fashioned about their playing.

The strings in particular have a crispness of attack and a clarity

of articulation that passes easily for period instruments. The

harmonic parts of the continuo team of course are on period instruments

and Bicket himself plays some of the harpsichord recits. Also

the trio of recorders in the famous bird aria Augeletti che

cantate are excellent.

All in all, it is a distinctly mixed bag. Musically

there is much that is satisfying. But then David Walker just does

not bear repeated listening. Visually there are too many eccentricities

many of which would not have been visible to the theatre audience.

When this writer thinks of filmed opera the yardstick is always

the superb Joseph Losey film of Mozart’s Don Giovanni made

in the 1970s and filmed out-of-doors using Palladio’s Villa Rotunda

near Vicenza as the main set. In that example, film was used to

enhance the nature of opera - a landscape where song is the natural

form of communication. It all made sense. The DVD revolution is

making many operas available for home consumption, and the cost

differential in the production of something like the Losey Don

Giovanni compared to a couple of cameras in the theatre must

be taken into account, but it seems that the full potential of

the medium has not yet been realised.

Peter Wells