Something

of a rebel as a Royal College of Music (RCM) student, Eugène

Goossens recalled, in his autobiography, Overture and Beginners,

that, Stanford, his teacher regarded him as ‘a lost soul’ for

listening to such ‘pornographic rubbish’ as Richard Strauss’s

Elektra. Undeterred, Goossens went on to absorb such ‘modern’

idioms as well as those of Debussy and Ravel in his works including

this deliciously melodic and romantic sonata, written in 1918

and first performed at the Wigmore Hall by Albert Sammons (its

dedicatee) and William Murdoch on 1st May 1920. Goossens

remembered that the première was a great artistic success

‘They play it con amore’ and he was so impressed by the

artists’ performance that ‘he despaired of ever hearing it played

that way again.’ I doubt very much if he would have anything but

praise for Mitchell and Ball’s intensely heartfelt performance;

so poetic in that lovely central Molto adagio and

so invigorating in the breezy final Con brio.

Another

precocious RCM student, William Hurlstone, died at the

tragically early age of 30. He is best remembered for his Piano

Concerto and Fantasie-Variations on a Swedish Air (both

to be heard on one precious album recorded by Lyrita Recorded

Edition SRCS100 many years ago, alas no longer available). He

composed a number of chamber works including a rather eccentric

Phantasie Quartet in E minor that won him the 1905 Cobbett

Prize (another Lyrita album SRCS117 still consigned to vinyl perdition).

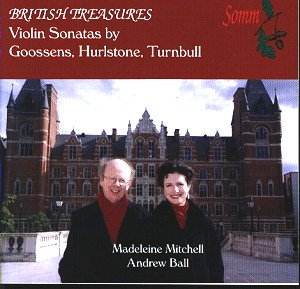

This Violin Sonata in D minor was first performed at the Royal

College of Music (pictured on the album cover above behind the

two soloists) on 3rd February 1897. The mood is more

introspective than the Goossens work with a shadowy thread through

its melodiousness. A juxtaposition of sustained melancholic lyricism,

and livelier dance material constitutes the central movement effectively

combining elements of slow movement and scherzo. The final Allegro

scherzando brings sunnier, sprightly music with some quirky

harmonic progressions offering contrasting depth, and surely there

is a passing hint of Elgar in Chanson de matin mood.

Percy

Turnbull, the third RCM student featured in this recital,

studied composition with Holst, Vaughan Williams and John Ireland,

besides attending classes with Dunhill, Dyson and R.O. Morris.

Winning the Mendelssohn Scholarship and the Arthur Sullivan Prize

he won the approbation of his teachers. He became highly regarded

as a recitalist at the RCM, at the Wigmore Hall, and as an accompanist

in the early days of British radio. His one and only extended

instrumental work, this Violin Sonata, was composed in 1925. It

was first performed on 24 June at the RCM with the composer at

the piano partnering Marie Wilson. It then languished until it

was revived in 1983 by Ann Hooley and Robin Bowman at the University

of Southampton. There is an attractive out-of-doors freshness

about the opening lyrical Allegro (but with a sombre melody low

in the violin’s compass) which like the Goossens work nods towards

Debussy and Ravel - and John Ireland. The violin’s yearning melancholy

and drooping piano chords, suffuses the lovely central Andante

moderato that leads to a passing defiant statement by the piano.

Turnbull’s playful Finale recalls Ravel particularly in the piano

writing but it is the violin’s lovely nostalgic central song that

haunts.

Three

gorgeously, lyrical, romantic British violin sonatas played with

great affection by Madeleine Mitchell and Andrew Ball. Highly

recommended.

Ian

Lace