Lennox Berkeley: John France interviews Richard Stoker.

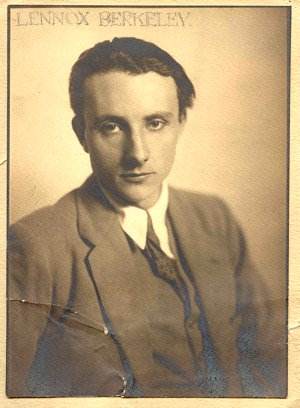

Lennox Berkeley 1925

Lennox Berkeley 1925

Could you outline for me the circumstances of your first meeting with Lennox and how you came to study with him?

My very first meeting with Lennox was in September 1958, my first week at the RAM, although I had been a long time in touch by letter and had sent him one or two scores which he'd very kindly returned. These were the scores I had also sent to Britten, and with many others to Arthur Benjamin, also. Benjamin was the first who'd invited me down from Yorkshire to London and I'd had quite an intensive consultation with him. I'd asked him if he'd teach me but he'd said he only taught piano (Britten had studied with him) but that Matyas Seiber and Lennox Berkeley were the best teachers. As Seiber only taught privately (Fricker had studied with him) I decided the best way forward was to get a scholarship to the RAM. Lennox also wrote back to say he'd teach me if I got into the Academy. In the meantime I'd had a meeting with Britten in Manchester and I told Ben that Lennox would teach me. He also thought Lennox would be the best choice. It took over a year to get to London. In that time Harold Truscott had started teaching in Huddersfield so I began over a year's intensive study with him. So my ambition was to reach Lennox somehow and I finally did, but what a long wait it had been!

What impressed you with his personality at this early stage?

His modesty was immediately noticeable, a cheerful disposition and friendly attitude, often fastidious in dress but also liking the casual. He was thoughtful most of the time, but always unassuming. His was a gentle, relaxed personality showing incredible empathy, his personality was strong and individual which came out in every note of his music. Added to these qualities he had perfect taste and a remarkable wit and humour, the latter quality being often found in highly creative people; in fact Lennox was nearly always joking, but his humour was deeply ironic, a trait of which the French are masters, so it was not surprising to find Lennox to be partly French. It was obvious from our first meeting that he could be a perfect host, a drinks table was always near at hand and unless he was teaching he would always keep the whisky, gin or brandy flowing. He liked a Scotch with a tiny splash of soda: when I had mine with water he was concerned I'd drown it!! His obvious feeling for his composition pupils was shown that evening when he told me he'd refused to teach in the tiny room the RAM had given him on the fifth floor, and had received special permission from our Principal Tom Armstrong to teach his few principal study composers at his beautiful home in Little Venice, west London. I noticed much later that his personality was very much the actor's, a sort of John Gielgud figure often resplendently dressed, often sporting a bow tie and silk handkerchief well drooping from the top pocket - he used the handkerchief frequently. It soon became apparent that Lennox, who'd at one time seriously thought of becoming a priest, would have made a superb actor if his calling for composition had not been so strong. (He was far too humorous to have been a cleric.) It was hard for me, the Northern lad, to understand the varied personas Lennox could present to different company and in many situations. He in many ways resembled an aristocratic court jester - a gentleman jester.

Did you know much of his music then? If so what?

Quite a lot: the String Trio, the St Teresa of Avila work, the Violin and Piano Sonatina, the Divertimento, the String Serenade, the Operas: Nelson, Ruth and The Dinner Engagement, the Horn Trio, Piano Sonata, Six Preludes, Three Impromptus, Recorder Sonatina, Four Concert Studies, String Quartet No 2, Symphony No 1, Viola Sonata, Introduction and Allegro (violin), many songs including How Love Came In and the Three Greek Songs, so many choral pieces, including the great Stabat Mater, the Piano Concerto, the Two Piano concerto, the Sinfonietta for Orchestra, the Flute Concerto composed for John Francis, his variation on Sellinger's Round (with Britten), and of course Mont Juic (also with Ben). (I discussed the latter work with him, and although each composer had written two movements each, it was still a secret who had composed what, but I got the distinct impression that they may each have orchestrated the other's movements.) Then there was the BBC documentary Wall of Troy, and the film scores for: Hotel Reserve, The First Gentleman, Out of Chaos, and Youth of Britain.

Was his music much performed in the late 1950s and early 1960s London?

On the whole, yes, also it was often broadcast. You see, after he met Britten in Barcelona in 1936 their names were tied together/ paired just as Byrd and Tallis, Bach and Handel, Schubert and Beethoven, Hindemith and Stravinsky, it was always Britten and Berkeley for about three decades till in the sixties it was Britten and Walton, then finally when Tippett's later operas were mounted it was Britten and Tippett. From the thirties through to the sixties Britten and Berkeley had many performances together, often with premieres in the same concerts.

Do you have any reminiscences of a particular performance or concert?

Lennox invited me to a Prom when he conducted his Five Pieces for violin and orchestra with Frederick Grinke. At the RAM his Dinner Engagement was staged and Lennox found that the librettist's name was missing from the programme: as the librettist was present Lennox insisted that a correction slip should be printed at the very last minute, so he wasn't as easy going as people often imagined. I also attended his Missa Brevis premiere at Westminster Cathedral. I remember a lovely Park Lane Group birthday concert with Richard Rodney Bennett and Susan Bradshaw playing piano duos and those wonderful Five Auden Songs were performed. At the opera Castaway Lennox had given me a seat next to Britten: this was the London premiere of the work. Then there was the Janet Craxton premiere of his Oboe Quartet. Lennox came to hear my own opera Johnson Preserv'd : he mentioned that the artist playing my Boswell had created the premiere of his Nelson at Sadlers Wells; when I said that the singer hardly ever remembered the director's positions he said the same had happened in Nelson and had not helped the opera's success. I remember at the end of my opera he clasped his hands together above his head in a friendly gesture of approval, very encouraging of him. I remember he attended his students' performances at the RAM: he would read his Times until the work started, and leave quietly afterwards, sometimes stopping to speak to Tom Armstrong the Principal.

Did you ever play or conduct any of his music?

Yes, I performed Lennox's popular Six Preludes for Piano in Huddersfield, and later at the RCM in London, and I remember conducting the St Teresa Poems with a Contralto and String Orchestra.

Student Days

You were a student with Lennox from 1958 to 1962 when you were in your early twenties

Well I was 19 when I started with him. I remember the terrible London fogs and people dying in hundreds that winter. Things had certainly changed by 1962: we were entering an exciting period, then I went to Paris until 1963 and was there when Lennox's close friend Poulenc died.

What brought you to study with him?

He was recommended as the best teacher for me by Arthur Benjamin and a Scholarship to the RAM made it possible. At the same time Lennox's music was a great favourite of mine, equal to my love of Ben Britten's, but I was particularly attracted to Lennox's piano works, whereas Britten's piano solos were few apart from Holiday Diary (dedicated to Arthur Benjamin) and the Piano Concerto (dedicated to Lennox). Britten's piano writing was limited to two-piano works or the song accompaniments. Lennox and Samuel Barber attracted me, as they both composed first-rate Piano Sonatas. So I was fascinated that Lennox was teaching at the RAM.

What was his teaching style?

Lennox well knew that teaching composition was impossible, he knew that a teacher could only guide and encourage a young composer, but Lennox had a very rare gift as a teacher, he could teach you without you knowing you were being taught. This is exceptional: it comes from people with much empathy. He would say: 'I'd do it this way, what do you think?' Then we'd discuss it and, instead of arguing the point, he would leave it, change the subject, then later, say at night in bed, or next day, or even a week later, I'd often realize he'd been right, and it sort of stuck! Lennox also complimented any successful passage or idea or chord sequence or counterpoint but he rarely criticised adversely: this was very clever, I know it works from teaching my own pupils; as you can imagine, he was extremely sensitive to a pupil's feelings.

Lennox Berkeley with Freda

Lennox Berkeley with Freda

Can you describe a typical class/tutorial session?

I always had something new each week, so we'd discuss this for say half an hour at most, then I would ask to see his work which was usually laid out on his study desk drying in the sun from the window. He was always pleased to show this to me and we'd play it through and discuss it: I learned a lot from his works. If there was any time left we'd play through his favourite Mozart scores as duets - he loved playing duets, out would come the Rigoletto full score, he loved the duet with Sparafucile, or the Hindemith Piano Duet Sonata, then often with all his pupils the full scores of his beloved J. S. Bach Cantatas, he seemed amazed that I could play from the C clefs (Soprano, Alto, Tenor, Baritone) quite fluently, but I had been trained earlier in them by Harold Truscott. Near the end of the lesson Freda his wife would bring us tea with biscuits or cake, then she'd remind him of the time. When Lennox discussed his own music with me he often went into a slightly somnambulistic state (shades of Schubert) and he'd feel for his pipe and light up and I'd smoke mine too, the room was full of smoke by the time the next pupil came in, often very late. Lennox kept his pipe at the end of the keyboard, I remember he liked Balkan Sobrani, and Four Square; when I introduced him to Baby's Bottom he was in fits of laughter and the fact we had to open it with a tin opener also amused him!

What did you learn compositionally from him?

To be myself, try not to change too much but develop my own style. Test every part to make sure it was what I really wanted to compose, and develop all the ideas, above all make the rhythm and inner rhythms telling throughout and make the form evolve or even let the music find its own forms. Above all to try to compose something that would communicate with the listener, economy was essential and to analyse the great masters whose music I loved, not so much the music I didn't enjoy; he well knew a style was formed by what an artist loved themselves.

Did he encourage you to listen to avant-garde works?

No, never, I think it was the other way round: we looked at Wozzeck, but I think he was influenced by this through Britten. No, he suggested Hindemith, all Stravinsky he loved, the Bartok works, especially the string quartets, and Frank Martin, but he was soon back to Mozart or J.S.Bach. He had little time for the second Viennese school or later music. He loved Verdi and we would go through Falstaff, we were fascinated by the vocal fugue in the final act.

Did he utilise his own music as examples?

No, never. It was only when I persuaded him to show me the scores, he knew full well how dangerous it was to influence a pupil with his own style, too much of that went on in those days. He was extremely modest about his own achievements and music, in fact I know he soon forgot his own works, large scores were found later on in his life that he'd forgotten. Lennox was altruistic, thinking more of others and the future, never looking back over his shoulder. It was always the music of others he talked about, never his own unless pressed. One day, early in 1960, a large brown paper parcel lay open on the top of Lennox's C Bechstein grand piano. It contained a huge score of Britten's newly finished opera, A Midsummer Night's Dream. It was a copy of the original handwritten score, sent immediately for Lennox's opinion, prior to publication. We went through the work together, note by note, which meant that I stayed longer. The next week, when we came to Act III, we both agreed that this act contained the finest music.

What exercises in composition did he ask you to compose?

None whatever, he realized that I'd been thoroughly grounded by Harold Truscott. He did say that the study of counterpoint could be very useful, but he had little time for text book harmony, which naturally endeared him to his pupils!

What did you compose under his aegis?

So very many works. Many Sonatas, Trios, Quartets, Song Cycles, an overture, two suites, a children's opera, very many other pieces, something finished every lesson. My Sonatina for Clarinet & Piano (Chandos) was written then.

Did he give good critiques of your music?

He was always very thoughtful, tested everything at the keyboard slowly - frequently asking if I really 'meant' what I'd written. Always kind and encouraging, I never remember disagreeing with a single point. I did notice that if he praised something a lot I'd go on to write more like it, so I think this was part of his great teaching, he was a master composer and an equally masterly teacher, such a great gift to have. If he said nothing about a passage you might wonder if it had been successful. Unlike Fauré he never had to apologise about being wrong, as most others have had to do. Cleverly, he only over-praised my work if he wanted me to continue in that vein.

You have used serialism to good effect in your works yet Berkeley did not begin to move towards serialism until early nineteen sixties.

Kind of you to notice, yes I'd experimented from the day I came across a Paul Klee painting in around 1951 - it seemed to suggest serialism to me - but I didn't use it much until my studies with Nadia in Paris in 1962. It was around this same time that Lennox became interested in it, and it began to develop in his oboe sonatina.

Did he encourage the use of serialism?

I did show him one or two pieces: he used the same criterion on them as on other works, seeing if they worked 'as music'. He certainly never dismissed anything, seeming pleased that I was aware of what was the climate. He was too civilised a person to be critical. He would certainly never encourage serialism to a pupil, it would be foreign to his nature. Much later I did use the eleven notes of his theme from the oboe sonatina first movement for my own Diversions on a Theme of Lennox Berkeley for piano duet: he was delighted I chose this theme for my own use.

I understand that Mathias, Bennett, Maw, Bedford and Taverner were also his students? Do you have any anecdotes about any of these or other composers in relation to Lennox?

When I started, Bill Mathias had just left the RAM, he came into the canteen one day brandishing his first published composition by OUP and waved it at his girlfriend, later to be his wife. Lennox thought him incredibly gifted, as we all did: Lennox was so impressed by the carols and the piano works with orchestra. I'm absolutely sure that Bill admired him as a teacher, and he was one of his few pupils to be influenced by Lennox's strongly individual style. I know Lennox continued to admire Mathias's works greatly.

Richard Rodney Bennett studied with Lennox: he moved on to study with Howard Ferguson, but he and Lennox remained the closest of friends. Richard was already fully formed as a composer when he entered the RAM. By 1958 he'd already composed fine film scores and Lennox was thrilled that Richard and Susan Bradshaw had gone to study in Paris with Boulez. I remarked at Richard's successes to him: he replied 'He's incredibly gifted and he always keeps a letter in the post'.

Nick Maw had also just left when I got to the RAM: Lennox was pleased that he was going to his own teacher Nadia Boulanger. Nick stayed only briefly with Nadia, then went to study with Max Deutsch. Lennox thought Nick had a great future and soon works such as the Nocturne were receiving critical acclaim in the Sunday Times. Lennox was delighted.

David Bedford often had his lessons just before or after mine. If Lennox and I were in the front study, we would hear David's motor cycle being revved up outside: I knew I had only ten minutes left to look at the Berkeley manuscripts. It took David quite a time to get out of his helmet and riding suit, which he left in the hall. We all three sometimes had tea together. Lennox was interested in a long work David was writing at the time - an opera on an Edgar Allan Poe theme, I seem to remember.

John Taverner's early works impressed me greatly, such as Cain and Abel, and the piano concerto. Lennox said he would achieve great things.

Peter Dickinson, who came from Cambridge University, and studied with Lennox in 1956, has become an authority on him, publishing an excellent book on his works and various biographical articles in journals and reference books.

Lennox had other pupils: one had been with him over a year. Lennox said: 'They say he has something but I've not found it yet! ' Another was an ex-pupil of Cornelius Cardew: 'He has nothing new each week so he plays the bassoon to me ... I'm learning a great deal about the bassoon!!'.

The big works of this period were the Concerto for Piano & Double String Orchestra Op.46, the Second Symphony; the Missa Brevis, the Overture for Light Orchestra & the Violin Concerto Op. 56. Were you present at any of these premieres? Did he discuss these works with you or the other students?

The first works he showed me and we went through in detail were the Guitar Sonatina, The Sonatina for Piano Duet which we often played through, and the Auden Five Poems (a major work) - he was seeing Auden around that time. Then one day we went through the Two Piano Concerto written ten years earlier: he was rearranging it for Two Pianos (three hands) for Phyllis Sellick and Cyril Smith, and then the Two Piano work with String Orchestra Op.46; we also played the early String Trio and Flute Concerto.

He said no other flautists could perform it for years because John Francis had the rights as part of the commission, something he'd never do again and hoped I'd not do either! We played the early recorder sonatina: he said he preferred it on the flute, as he did not like the recorder. At this point I asked him if he liked a vibrato on the flute, yes he said, living in France all those years he'd got used to it. I was surprised, but this is obviously why he liked James Galway's playing much later. Then I found him working on the Second Symphony which he'd started sketching two years earlier in 1956: he showed me this in detail as he composed it, week-by-week - there was not much time left before it would be needed. The Violin Concerto was a sudden commission from Menuhin, and Lennox had to write it quickly, and he agonised over whether it would be ready in time for the Bath Festival. I remember he was held up by writer's block, but luckily not for long; it was ready in time. He knew how good it had to be for Menuhin, and I was impressed by the work.

I seem to remember him working on the Overture for Light Orchestra whilst I was on holiday: he didn't like the word "light" in relation to music!

Then he was extremely excited one day: he'd started the commission for Stratford of the incidental music for The Winter's Tale. I'm sure I was one of the first to hear it: he asked me if I liked the music for the statue coming to life. After my Truscott training I preferred absolute music.

One memorable day for me was hearing Lennox play through the Piano Sonata written for Clifford Curzon in the early forties. Near the end Freda came in saying that she liked that work. It is disgracefully neglected. Now the Missa Brevis was another story. He showed me this soon after looking through Britten's own Missa Brevis. They were both written for George Malcolm and his choir at Westminster Cathedral. Lennox invited me to the premiere there. This reminded me of how earlier Lennox had taken me to hear the Britten premiere: when we got inside the cathedral he said: 'There's Ben at the front, let's join him.' Lennox insisted that I sat in between them. Ben was alone, dressed in a light grey summer suit. Lennox was in a black suit and had liberally used his after-shave powder which was all over his hands, his cuffs and his collar and tie (I thought it was special for the Catholic service, but I think he'd had an accident with the powder and hadn't had time to look in the mirror). After the performance we all three went out together and talked about the performance. After dropping Ben off Lennox gave me a lift back to Hampstead where I lived. It was a memorable day for me. Also I seem to remember that Ben had composed the Missa Brevis in a single day!

I'm not sure what he discussed with his other students: young composers are not only jealous of each other but secretive too.

Do you have any thoughts about these works?

Although written extremely quickly, the fiddle concerto is a fine work and shows how Lennox like all really great composers could work under extreme pressure, and for a great soloist it had to be first rate or he wouldn't have conducted it.

The Second Symphony. The gestation of this piece: can you give an outline?

It was already started when he showed it me, about eight fully scored pages, then he showed me it every week. He said he'd been sketching it for two years and was not at all happy with it. I liked what we played through. One day he was extremely depressed: it turned out he had a serious dose of writer's block and he explained it to me.

Writer's block - why did this happen?

I think he was happy composing the symphony in his own time for his own pleasure, then when it was suddenly wanted it became too much. It went on for about three weeks - no progress. Lennox was devastated; he told me it had never happened to him so badly before.

How did you get involved in assisting him?

He suddenly asked me how I would go on! He was holding the partly finished full score. I was very flattered that he should ask me, my recent studies with Truscott gave me the confidence to suggest ways he could develop the ideas. After all this time I cannot remember exactly where he had got to but I know it was just before a development section, I just said what I'd have done and he seemed pleased. He was using me as a mirror. The following week he said he'd taken my advice and it had worked, so you can guess how pleased I was. I told no one about this until very recently.

Was it ideas or notes or just talking him through possibilities?

It was all three: taking his ideas I suggested different ways I thought he could progress and lead into a recapitulation, I wouldn't have dreamed of suggesting new notation - I could tell he had enough material already written. I often wondered if it had been part of my training. Only a composer as modest as Lennox would have asked me my opinion, he was really suffering at that point though. The writer's block happened again with the Menuhin concerto. It was far less severe, but had to be sorted out more urgently. This was possibly due to the close proximity of the Five Pieces for Orchestra for Grinke - the Menuhin Concerto on top of this was too similar a challenge, but he managed it. We discussed a passage in the violin concerto, but this was much less of a problem. I was such a novice too; it was a huge boost to my morale.

What is your opinion of this work [the Second Symphony] after 45 years?

I remember my old friend Nicholas Braithwaite conducted it years later on an LP: when I heard this broadcast on the radio I was greatly impressed. Lennox had revised the orchestration in 1976, which shows how rushed it had been in 1958.

How do you think it fits into Berkeley's own cycle of symphonies? British Symphonies?

Extremely well. You see it is more serious and original than the first symphony and more substantial than the serially influenced compact third symphony, and the fourth repeats the seriousness of No 2 plus the lightness of the First. A wonderful achievement from a composer who had originally been called a miniaturist! Although more substantial than the other orchestral works, the Symphonies retain an element of lightness, which means that they are quite easily assimilated by a new listener. I would describe their style as English, but with Gallic tendencies. Paradoxically they also remind me of Brahms's glorious Four Symphonies: I am sure that Lennox revered Brahms's craftsmanship and tried to emulate him. It worked too. Lennox's Symphonies are less ponderous than Rubbra's, more varied than Walton's and Vaughan Williams's, more approachable than Tippett's. A great addition to British music.

On 2nd July 1983 Lennox attended a Birthday Concert at Cheltenham Town Hall when a performance of Variations on a Theme by Lennox Berkeley was given. It was based on a theme from the Reapers Chorus from his opera Ruth. Many composers, who were former students, each wrote a one minute variation. These included Sally Beamish, Christopher Headington, Richard Rodney Bennett, William Mathias and yourself. Can you tell me how this piece came into being?

Yes, I remember it because my father, who was the same age as Lennox, was in hospital and couldn't record the broadcast for me, but luckily one of the composers gave me a recording, I will always be grateful to him for this.

It was the brainchild of Sir John Manduell, a pupil of Bill Alwyn and Lennox. John loves Lennox's music and for the 80th Birthday concert he wrote round inviting us to compose the variations just as Ben Britten had done with the Sellinger's Round variations for Aldeburgh. It all worked incredibly well and John put it together very tellingly and had the parts copied. I believe Chesters publish it in their Hire Library and after it was performed and broadcast (twice), I bought some pipe tobacco with my Royalties. The Philharmonia played really well, there were excellent variations by John Taverner and Chris Brown as well. John chose the extract from the opera Ruth because it was one of Freda's (Lady Berkeley's) favourite works: I seem to remember it was dedicated to her.

Did the composers co-operate or was it serendipitous?

Any tales about this work worth preserving for posterity?

It was put together purely by chance, plus Sir John Manduel's excellent taste in assembling it. We also had precise instructions in a letter from John, plus dates etc. It was quite an achievement by all concerned. Radio 3 broadcast it live too: anything could have happened, but it didn't, there was quite a delay before it began, getting all the composers and their friends into the Town Hall from the reception in the Green Room. I seem to remember the Nine O'Clock News was late that night!!

Does it deserve a hearing this year or was it ephemeral?

No, it certainly wasn't ephemeral, it was very successful, perhaps as successful as A Garland For The Queen was fifty years ago; Lennox composed a choral setting for that work too. Yes it should be done again. The BBC may still have a recording, or it could be hired from Chesters: any enterprising Symphony Orchestra could perform it.

Personal Influence

A number of critics have noticed many nods in Berkeley's direction in your own music.

I am flattered. Any influence was purely intentional. I certainly have not copied his style, but have tried to achieve the feeling of repose he so often discovers, also the melodic beauty and economy of means. It is also because we both studied in Paris and with Nadia.

What were the key Berkeley works that influenced you? (If any)

So very many, not so much from the scores, but from what I remember of his music. The remarkable Horn Trio, the Violin Sonatina, the early String Trio, Nelson, nearly all his piano works, the Guitar Sonatina, the Flute Concerto, the Sextet Op.47, the Sonatina for two pianos (never heard now), the Piano Duet Sonatina, Oboe Sonatina, Oboe Quartet, Partita for Orchestra, all the twenty-seven or so liturgical settings, all the Songs (the Auden, Donne and two Ronsard works in particular, plus of course the Teresa masterpiece which is as sublime as anything Ben Britten composed), all the Piano works (which is about a quarter of his oeuvre, the major Stabat Mater (rather spoiled for me by the overt Stravinsky influence), The Castaway (an opera that was rather disappointing, performed as it was with Walton's splendid The Bear). Otherwise, I've liked all the other Lennox Berkeley works.

What did you learn from him and how did you apply this in your own works?

The economy, the melodic interest, the counterpoint, the way he was stimulated to compose for unusual combinations, the rhythmical interest, the inevitable momentum which should lead somewhere, above all the wish to communicate with the listener.

Berkeley was friendly with Ravel & Poulenc, and had studied with Nadia Boulanger. This made him a cosmopolitan composer. There is no sense of Englishry or overt pastoralism in his music.

Not the old fashioned sort. Berkeley and Britten had to do something. They had to get some new blood into British music. The best way was by being cosmopolitan.

Those of your works that I have listened to tend to be devoid of these stylistic tendencies too.

You are absolutely right: I think both Lennox's and my own music will seem very English one day, it's just that we have both allowed a breath of fresh air from across the Channel to improve our Englishness. Lennox's Serenade, Divertimento, String Trio, Nelson opera, Teresa poems all sound purely English to me now as most of Britten's works do, the European influence was to make our works English and at the same time cosmopolitan, and it works.

Does this reflect your musical ethic?

Yes, I think it does, I certainly avoid pastoralism, but at the same time would love my music to sound as English as Elgar's, or Holst's, or Britten's, or Berkeley's. Our really great music of the 16th and 17th centuries was influenced from all over Europe: Britten and Berkeley knew this - look at a masterpiece like Les Illuminations, the Frenchness is not just because of Rimbaud's words. Our Englishness needs a balanced influence from overseas to make it more English, not less.

Did Lennox encourage you to study with Nadia Boulanger?

Yes he did. I'd written to Copland and Barber in the States but couldn't get a large enough scholarship to go there. Then the Mendelssohn Scholarship wasn't enough to take me out there either, so when I was awarded it, Lennox suggested Nadia, but I know he was a little worried about how dogmatic she'd become since he was with her in the twenties and thirties. 'It was so cheap to live in Paris in those days', I remember him saying. By the sixties she had become immersed in Stravinsky. But I survived and learned a tremendous amount from her about composition, art and life. Nadia was not the natural inspired born teacher Lennox had been, but it was good to get abroad and soak up the French influence. I remember Lennox saying as we walked on Primrose Hill near the Roundhouse: 'Don't stay abroad too long: four months should be enough for you or they soon forget you over here and you'll have to start all over again!' Then he said: 'Whatever you do, don't change'. Sir Arthur Bliss said to me before I went to study with Nadia: 'Don't believe all she says!' I know he was worried that she might not be right for me, but she was. Whilst over there I had a visit from Lennox and his wife: they bought me some liver from a market. I visited their hotel: they often stayed at the one Oscar Wilde had died in. I seem to remember the room was the one of the famous 1901 photo of Wilde on his deathbed. Lennox was excited to see the haunts of his youthful student studies in Paris.

Lennox Berkeley's Legacy

His music has suffered an eclipse. There are few CDs available and his music is heard infrequently in the concert hall. Yet his immediate contemporaries - Walton & Tippett are way ahead in the popularity stakes.

It is such a pity this has happened but I am quite sure it will be only temporary, you see Britten, Tippett and Walton are more like Wagner, Strauss and Berlioz, whereas I like to think of Berkeley as a sort of English Brahms - though many people have called him the English Fauré, the English Poulenc and the English Barber. It is amazing to me how he resembles the great German composer: Horn trio, three string quartets, four symphonies, three violin sonatas (if you include the sonatina), a remarkable set of piano works (a third of the works) and songs, also extensive choral and religious music (27 separate movements), Lennox's melodies can even be whistled like Brahms, rare for a composer these days: The St Teresa Poems, the String Serenade, one of the Auden songs, parts of Nelson and The Dinner Engagement are examples. Lennox always said his new works needed to be heard at least twice. The popularity stakes are not all that important in the long run. Composers like Berkeley, Rawsthorne (whom Lennox always promoted), Holst, Ireland, Howells, and Moeran will come into their own one day as Finzi has done recently, it is only a matter of time, they were all excellent craftsmen.

The majority of listeners who know any of his works will be familiar with the Serenade for Strings and little else.

Also the Divertimento, the St Teresa Poems, the Symphonies, the Flute Sonatina, the Sextet - they all get broadcast.

Why do think this eclipse has happened?

I wouldn't say it's a total eclipse. Lennox's music has been broadcast quite regularly. There is now a Lennox Berkeley Society as well.

Do you see any signs of a revival?

Certainly, a gradual one, hopefully by May 2003, the Centenary of his birth, things should change.

What is, in your opinion, his finest work?

Without doubt his three act opera Nelson Op 41, to a libretto by his great friend Alan Pryce-Jones. I remember it as full of melodies and ensembles written on the grand scale. It has a lengthy plot and has some contrived situations but nothing is wrong with its music, it contains some of Lennox's finest music, it could be popular too, a great English subject from a composer who had an aristocratic nautical background. He put over two years' work into it for its premiere at Sadler's Wells in 1954. There is also an orchestral suite from it, which we hardly ever hear.

Do you agree with the opinion that he worked better on a small rather than a large canvas?

No, not at all, that was an early myth: I know that criticism irritated him. He had little time for the critics who were not helpful and constructive. Don't get me wrong: Lennox was not obsessed by the critics as Britten was. He would put up copies of his better notices on the mantelpiece in his front study for all to see. He was just as happy with substantial works as with smaller ones. He was fearful of boring the listener: to his mind, the worst thing one could do. It's just that his Symphonies retain the lightness of the smaller orchestral works, he is no miniaturist, it is just that he says what he wants with the least number of notes, like Mozart and Poulenc, and then stops. He is good both large and small, his forms are well thought out too, he is a master of economy. When minimalism settles down, hopefully Berkeley's music will be performed more. He has the very great ability to sound purely personal. A musician only has to hear a phrase of Berkeley's to recognize its composer: how many composers in history can do that?

What work would you like to hear revived for the centenary year? For me it would be the Piano Concerto in Bb.

That is an excellent choice, it is a masterly piece, I agree. Also the First symphony is full of tunes and the chamber sextet and the Horn Trio. EMI apparently have a recording of Kathleen Ferrier singing a concert version of the St Teresa Poems, how exciting it would be to hear it. Also why not release Pamela Bowden's excellent EP of it on CD? Then there's the withdrawn oratorio Jonah of 1935: Britten is said to have travelled all the way to Leeds to hear his friend conduct its premiere, and liked it - might it not turn up again? It would be fascinating to hear it. Lennox's pupil John Taverner wrote on the same subject, so perhaps Lennox didn't wish comparisons to be made? There are so many works worth reviving: what about the Piano Sonata written for Clifford Curzon?

Lastly,

Chandos are releasing a series of CDs of music by Lennox and his son, Michael. There have been criticisms that this is a misguided coupling of musical styles; their music is quite different and is not necessarily appreciated as an item! What are your views on this?

Not all their works are different: I was most impressed by Michael's beautiful Organ Concerto and also his choral piece for Linda McCartney's memorial CD. Lennox would have been proud of these two pieces that are not unlike his own. I well remember when he first told me Michael was composing he said in his typical way, leaning on the mantelpiece in the lounge and smoking his pipe: 'If all three of my boys become composers, perhaps I will be remembered like J.S.Bach and his sons!!!' A typical Lennox Berkeley remark. I can see him now at parties for his sons: they ran from room to room and he joined in. He had a wonderful family life and was so proud of them.

What about the other arts?

He was an avid reader: Julien Green, Nancy Mitford, Evelyn Waugh, Anthony Powell, Valéry, Gide, St Augustine, Thomas Hardy, John Donne, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Teilhard de Chardin, Ronald Knox. He encouraged the painter John Craxton by displaying and collecting his work (it is interesting that the Oboe Sonatina is dedicated to Janet and her brother John, not to her husband Alan Richardson who performed the piano part). The painter Caroline Leeds (Lady Hobart) told me that, as a girl of 17, she was staying on Jersey after the evacuation of the Nazis when Lennox came over to see what she was painting, he liked what he saw and encouraged her to continue. She found him a charming, friendly and modest man.

Do you have any personal anecdotes about Lennox and his relationship with you?

I mentioned what a great actor he could have been, well once as I was walking up, I think Camden High Street I saw Lennox coming towards me but a long way off: even from that distance I saw him recognise me, then as he came nearer he began to dance about elf-like around one or two people in front of him, then as he drew nearer he walked normally, then pretended to recognise me for the first time. He was dressed in his dark blue tight jeans which he loved to wear, long before they became fashionable: I don't know to this day what he was trying to say to me but I recognized it as an act for my benefit. He very rarely criticised any other composer, but he once said to me of a fellow-composer: 'You know he tries to make out that his operas are not produced at Covent Garden or Sadler's Wells because of his politics - they are poorly written, dull works in my opinion, nothing to do with politics.' He certainly knew what worked on the opera stage and was critical of any undramatic work, knowing full well how difficult opera is to write, needing a very special talent like Puccini's or Verdi's or Britten's. I'm sure Lennox had that special gift required for opera.

Going back to our first meeting, Lennox had been a guest on Woman's Hour a few weeks before - he told the story of a judge in Leeds sentencing a burglar who had stolen hundreds of 78 rpm gramophone records: 'Were the records pop or classical?' the judge enquired. 'Classical, your Honour.' The judge answered immediately: 'Release him! ... Case dismissed'!!! Clearly the theft of classical records didn't appear to the judge to be a crime!

When the Music Programme (Radio 3) was to be heard all day, Lennox was asked what he thought. He said, 'There might be some danger in the morning, in shaving to late Stravinsky!'

Another time Lennox and Freda were having lunch with me at my flat in Parliament Hill Fields; it was summer so the windows were open. As we ate we heard flute playing from a partially open window across the road. We could just make out a tall figure at a music stand. Lennox said, uncharacteristically for him: 'I should have brought a copy of my Flute Sonatina, then I could have crossed the road and popped it through the gap!' As we all laughed he added, 'Then you could have followed me across and popped your Sonatina through!'.

Richard Stoker/John France January 2003

Photographs reproduced with kind permission of Chester Music

see also

Lennox Berkeley by Peter Dickinson

Lennox Berkeley by David Wright