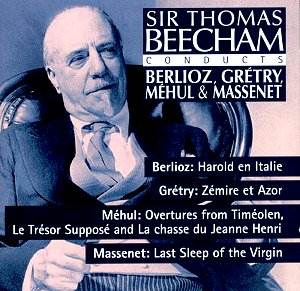

Beecham's love affair

with the Gallic muse was no temporary

dalliance. It can be traced from his

first concert to his very last. The

record catalogue also carries the evidence.

The splendid Sony UK Beecham series

keeps enthusiasts alternately satisfied

and on tenterhooks. For all that we

pour scorn on Sony at an international

level the artistic judgement and perceptive

choices of the UK and French outfits

continue to please. The notes for the

Beecham series are just as much an exemplar.

Whoever chose Graham Melville-Mason

to provide the commentary has nothing

to be ashamed of. GM-M's notes evince

the drudgery of research but cloaked

in brilliance of expression.

Beecham's Berlioz is

rightly famed. His Harold bloomed

from its beginnings in concerts with

Tertis in 1933, to Primrose in 1942

and 1952 and Riddle in 1953 and 1956.

With an orchestra in

which personality was not a dirty word

we find Gerald Jackson (flute), Terence

MacDonagh (oboe), Jack Brymer (clarinet),

Gwydion Brooke (bassoon), Dennis Brain

(horn), Leonard Brain (cor anglais)

and David McCallum (violin).

What strikes me about

this performance is Beecham's sauntering

'sprung' way with Pilgrims' March

and his silky seamless supercharged

continuity of line in Harold in the

Mountains and The Orgy. There

might be more snap and smash to the

Orgy but its smoothness of lyrical

line are compensation enough. Primrose

is steady, pliant, and responsive; the

ideal complement to the orchestra or

vice versa. The mono sound is secure

and, if this makes sense, very easy

and pleasing to listen to.

The fillers remind

us of the young Beecham poking around

the librairies and bibliothèques

of 1904 Paris. From these forays

he built his library of Grétry

and Méhul, Isouard and Monsigny.

The Zémire is a soupy

but uncongealed confection with a prominent

rounded line for the cello. The Massenet

is another classic lollipop in the Zémire

mould although the lovely fade at

the end gives signs of having been aided

by the technicians of the time. The

three Méhuls include some real

rarities. Timoléon is

lively and of a sweet though unsleepy

disposition - an approach to Mozart's

opera overtures via Berlioz. It sports

some mercurial flute solos. Le Trésor

Supposé is similarly shaped

but much more earnest; not as successful.

All is forgiven with the more famous

La Chasse (a classic of the 78

era). Honeyed work and sensitive playing

down to a silky pianissimo characterise

the introduction. From a serenade-like

tune of Mozartian 'fall' we move into

a magically balanced dialogue of hunting

horns sounding distantly. Then comes

an elegant chasse which has the grand

manner of Mozart's Jupiter and

the lightning strikes of Beethoven's

Seventh. The blast of the French horns

in the final pages is unforgettable.

Beecham soothes and

stimulates in this generous collection

of the familiar and the unfashionable.

Rob Barnett

see also review

by Jonathan Woolf