AVAILABILITY

www.sonyclassical.co.uk

Beecham performed Harold in Italy with three

elite violists, all British. The earliest performance, so far

as is known, was with Lionel Tertis in 1933, the middle ones were

with William Primrose and the last with Frederick Riddle. Although

no trace of his collaboration with Tertis now survives, fortuitously

this commercial Primrose recording has been augmented recently

by the 1956 Edinburgh performance with Riddle on BBC Classics.

Comparisons are, as ever, instructive. In the 1951 Primrose recording

the first movement repeat wasn’t taken – unlike the Edinburgh

broadcast – and there are commensurate gains in tension in the

live context whilst also losses in terms of audience coughing,

a few intonational concerns and a greater sense of the explication

of the luminous orchestration in the studio. Riddle-Beecham is

rather more full of nervous energy and declamatory élan

in the opening, with the soloist slightly slower and more ruminative

than Primrose-Beecham. In the second movement one is faced with

the studio veil of exquisite tonal shading or the live performance’s

infinitesimally greater sense of lyrical curve in the détaché

writing. Of the two recorded sounds the Usher Hall is less ingratiating,

the studio richer. Of the soloists Primrose is the more poised,

but he had the advantage of studio retakes, and Riddle’s understanding

of Beecham’s cantilever is distinguished. This is the only extant

example of Riddle’s Harold whilst Primrose of course set down

recordings with Koussevitzky and Munch. Incidentally his first

Harold was when he was co-principal of the NBC with Toscanini

conducting, a private recording of which the Italian conductor

invited the Scotsman to hear. I assume it’s still extant – a suitable

case for Guild (unless I’ve missed a commercial release of it

somewhere)?

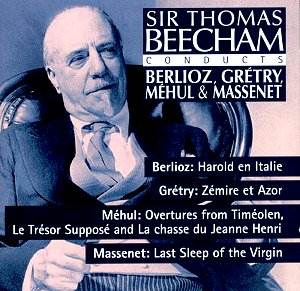

This all-French disc is additionally graced by

some long unavailable material. The Méhul gets some cracking

work from Beecham. The trumpets punch out in Timoléon

and the strings slash over the dramatic double basses. Works

like this were the fruit of Beecham’s long-held fascination with

late eighteenth century French music, fuelled by hours in the

Bibliothèque Nationale and Parisian bookshops in the first

decade of the twentieth century. He is very much the Grand Seigneur,

full of lyricism and swagger in the overture to Le Trésor

Supposé, and strong on exultant power. The biggest

of the trio of Méhul overtures is that for La Chasse

du Jeune Henri (strangely mis-titled on the disc as La

Chasse de Jeanne Henri) which features the distinguished

contributions of Jack Brymer and Gwydion Brooke. The suspenseful

string figuration ratchets up the tension, added to by Dennis

Brain’s immaculate horn calls, the marvellously vigorous but subtle

playing an apt reflection of Beecham’s affection for and interest

in the work. Balance is superb, the drama and vigour are predominant,

bagpipe drones are irresistible in their immediacy and everything

opens out into blazing sunlight. Beecham described this kind of

thing as Chivalric Romance and that’s quite as he plays it, not

least the blazing climax. Grétry’s Pantomime from Zémire

et Azor is one of my Beecham favourites but not in this performance.

I much prefer the touching intimacy of his 1940 LPO recording

with its touching single line string leave-taking to this rather

plumped up affair but the Massenet Last Virgin, as Beecham used

to put it, is beautifully veiled and intimate.

The 1951-54 monos sound full of subtlety and

depth in these transfers and Melville-Mason’s notes are characteristically

full of acumen and period interest – I’m glad he hasn’t relied

on Gramophone reviews, as he is sometimes prone to do. An exciting,

invigorating disc.

Jonathan Woolf