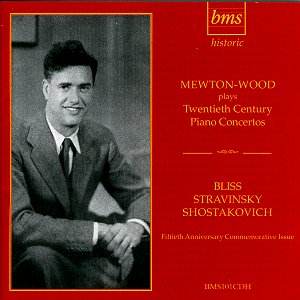

Just a few weeks ago I made a speculative purchase

of the newly released Somm CD of Noel Mewton-Wood and Sir Thomas

Beecham collaborating in Busoniís huge Piano Concerto (Somm-Beecham

15). I was amazed at the intensity of the performance Ė a live

BBC broadcast from 1948 Ė and at the tremendous playing of the

then twenty-six year-old pianist. Now along comes another example

of his extraordinary talent.

Was this Australian pianist another William Kapell?

In both cases these young musicians blazed all too briefly across

the musical firmament before dying far too soon (in Mewton-Woodís

case, tragically, by his own hand). Both left us tantalisingly

few recordings which show what they had achieved in what should

have been the early years of their careers Ė and which hint at

what might have been. This CD is issued to mark the fiftieth anniversary

of Mewton-Woodís death, in December 1953.

Unlike Kapell, Noel Mewton-Wood was never really

taken up by a major record company (something which he found very

frustrating) and the three performances which appear here were

all made for the small Concert Hall label. All credit to that

label for recording him in less familiar repertoire.

Mewton-Wood was a noted exponent of Blissís

Piano Concerto Ė so much so that Bliss wrote a piano sonata

for him. By coincidence, APR has just issued a CD of the very

first performance of the work, by Solomon and the New York Philharmonic

under Boult in 1939. Reviewing that

release my colleague Christopher Fifield quoted Nicholas Slonimskyís

verdict that the piece bore many influences of Liszt, Chopin and

Rachmaninov. I agree, but to that list Iíd add the name of Prokofiev

for his piano music comes irresistably to mind when one listens

some of the driving, percussive passages in Blissís piece.

Iím bound to say that though Iím an admirer of

Blissís music Iíve never been quite sure about the Piano Concerto.

It contains plenty of display and rhetoric but, Iíve wondered,

does the musical content match up? Well, hearing Mewton-Woodís

magnificent, hugely confident account (and, indeed, Solomonís

1939 world première reading) goes a long way to persuading

me of the pieceís worth. Mewton-Woodís very opening is terrific.

He plunges straight in, unleashing a veritable torrent of notes

(but then the titanic Solomon is even more urgent, I find). This

sets the tone for much of what is to follow in the outer movements.

The solo part bristles with difficulties but these appear to hold

no terrors for this young virtuoso. Indeed, supremely confident

in his own abilities, he seems to revel in the technical problems.

He plays much of the first movement with tumultuous power but

he is just as good at fining back his playing to do justice to

the more reflective passages (sample track 1, from 11í28"

to 12í35")

Mewton-Wood matches Solomon for nuanced sensitivity

in the slow movement Ė where the orchestra also rise to the occasion

Ė and his account of the dashing finale is also entirely successful.

Itís interesting to note that under studio conditions Mewton-Wood

is more expansive than Solomon in the outer movements, taking

a minute longer for the finale and a full two minutes more in

the epic first movement. The Utrecht Symphony Orchestra is sometimes

stretched (for example, the violins sound a bit undernourished

above the stave) and one is conscious that this isnít a world

class orchestra, whereas, even through the more murky recording

of the Solomon recording, one can tell that the New York Philharmonic

Ė Barbirolliís band in those days! - is high class. However, the

Dutch players most certainly are not disgraced. Capably directed

by Walter Goehr and, no doubt, inspired by their soloist, they

play valiantly and, in the slow movement especially, with some

sensitivity.

Iíll own up to the fact that Stravinskyís

Concerto is not one of my desert island pieces. I donít really

warm to his neo-classical style (still less to the acerbities

of his later compositions). However, Noel Mewton-Woodís account

is as good as any Iíve heard. The wind and brass players of the

Residentie Orchestra are not, perhaps, the most sonorous ensemble

(though in part that may be due to the age of the recording) but

actually in this sort of piece a certain degree of "cultured

stridency" is not inappropriate. Mewton-Wood is dextrous

and nimble in the first movement (where Goehr points the accompaniment

with acuity). He displays strength and gravity in the slow movement

and plays with drive and pungent vitality in the finale.

I was mightily impressed with the vivacious and

technically assured performance of the Shostakovich. This

work is primarily a jeu díesprit and Mewton-Wood is just

the man for this, throwing off a great deal of dazzling pianism.

However, he is equally successful in conveying the repose of the

Lento (track 8). I was also much taken with the superb,

silvery contribution of the trumpeter, Harry Sevenstern. His line

cuts through the textures beautifully, just as the composer surely

intended.

There is good support from the string orchestra

(a pick-up band of London session players?), especially in the

Lento. That movement is beautifully poised all round and

the performance touches real depths here. In particular Iíd single

out the wonderfully nostalgic trumpet solo (track 8 from 4í17").

The performance ends with a breathlessly exciting, whirlwind finale.

This is a very important disc and the BMS have

treated it as such. The transfers, by Bryan Crimp, are excellent.

The recordings are as old as I am but they have come up very well

though inevitably the piano sound can be a little clangy and not

all orchestral detail comes over with complete clarity. That said,

the recordings give a very faithful representation of the performances.

The documentation, though in English only, is absolutely outstanding.

John Amis contributes a very well argued and informative (and

affectionate) note about the pianist. In addition Edward Sackville-Westís

recollection, written for the programme of the Memorial Concert

in December 1954, is reproduced. Then John Talbot contributes

very good programme notes though they are rather dominated by

the details on the Bliss concerto this is perhaps understandable

since it is the least familiar of the three works. As if all this

were not enough William Mannís excellent thematic analysis of

the Bliss, with copious musical examples, is also reproduced.

Iíd say this is the best documentation for a CD that Iíve seen

for quite some time.

So, a very well produced disc enshrining some

first rate performances by a shooting star pianist whose brilliance

was extinguished far too soon. Whether he was a "great"

pianist is open to debate. His career was probably far too short

to allow for such a judgement. However, on the evidence of this

CD Iíd say that Noel Mewton-Wood had the talent to become great

had he lived and the performances included here are, I firmly

believe, touched by greatness.

I congratulate the BMS on the enterprise of this

release. I strongly recommend it and I hope that through it many

more people will get an opportunity to sample the phenomenon that

was Noel Mewton-Wood.

John Quinn

Paul Shoemaker comments

I feel John Quinn is a little too enthusiastic

over the Shostakovich, which is rushed and hence the hammy satire

is blunted. But he is too reserved in his praise of the Stravinsky,

surely the finest performance the work ever received. This particular

recording has been on my longer desert island list since it was

released.

The music of Stravinsky contains many ironies—ironies of

harmony, of rhythm, and, to credit Bernstein, even ironies of

style and mood. Stravinsky had had many bad experiences with performers

"interpreting" his music, the result of which being

that one or more of the ironies would be resolved and the complexity

of the work consequently reduced. Just after this recording, he

began issuing firm embargos against any "interpretation"

loudly criticizing any performance that went beyond playing the

notes exactly at the correct tempo and volume. Any performer who

attempted to add anything to a Stravinky performance was attached

for making errors, and hence Stravinsky performances fell into

a frozen routine, and have all sounded alike.

But not this one. Mewton-Wood plays parts of this music as if

he's really having fun, but not so much that the ironic solemnity

of other parts of the music is in any way compromised. This extremely

difficult balance is hereby brilliantly achieved; whether Stravinsky

appreciated it or not, I have no word. But for my money this is

one of the half dozen truly great Stravinsky recordings of the

century and a must for any Stravinsky collector.

The transfers are excellent, and anyone who knows what a snob

I am on that subject will appreciate it when I say that I couldn't

have done much better myself, IF I had had access to these excellent

pressings. But alas, my pressing of this recordings is far inferior,

and hence I am celebrating the release of this disk with champagne

and dancing, and so should you. After you buy it, that is.

Paul Shoemaker

British Music

Society