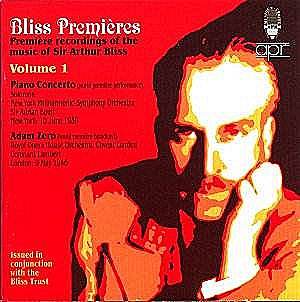

Bryan Crimp’s renowned work in researching and making

available historic musical events for CD takes an impressive step

forward with this disc of the world premiere performance of Bliss’s

piano concerto. The original acetate disc recordings are in the

International Piano Archives at Maryland USA, repository of much

significant archival material relating to the instrument. Despite

unavoidable deterioration over the years it is possible to experience

once again the thrill of the occasion from the discs, and where

small parts went unrecorded (during the interchange between a pair

of turntables) patching has been used from Solomon’s 1943 recording

for HMV with Boult and the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra.

The shellac recordings of movements from Adam Zero come from

the composer’s widow. Any hiss and crackle only adds to the flavour

of the historical context, so in this reviewer’s opinion, the transfers

are absolutely first-rate in both works and a tribute to Mr Crimp’s

labours of love. He has also written an excellent appreciation of

Solomon, called ‘Solo’, which I commend highly to the reader.

Bliss wrote the concerto to a commission from

the British Council in 1938 for performance at the British Week

of the New York World Fair in the summer of 1939. He had been

a juror the previous year on the Ysaÿe International Piano

Competition and came away highly impressed at the standard of

virtuosity of the competitors. Clearly this was still affecting

him when he wrote his concerto. It is an awesomely difficult work

neatly summarised by Nicolas Slominsky as ‘Lisztomorphic in its

sonorous virtuosity, Chopinoid in its chromatic lyricism, and

Rachmaninovistic in its chordal expansiveness’. Solomon’s playing

has unerring accuracy and confident abandon from the very start,

and it is hard to believe that Bliss had to give him a gentle

push on to the stage of a stiflingly hot Carnegie Hall because

he was too nervous to go on. Boult is a marvellously sympathetic

and supportive accompanist, and the orchestra play with a naturalness

which belies what must have been unfamiliarity with the Bliss

idiom. Later exponents of the concerto were Gina Bachauer, Trevor

Barnard, Noel Mewton-Wood and, nearer to our own day, John Ogdon

and Philip Fowke but it must have been a hard act to follow even

this baptismal performance by Solomon.

Adam Zero is the third of Bliss’s full-length

ballets (after Checkmate 1937 and Miracle in the Gorbals

1944), and in Wilfred Mellers’ view ‘the element of physical movement’

in the dance picks up with Bliss where Purcell left off … quite

a leap in time. Adam Zero is an allegorical comparison

between a man’s life and the four seasons from birth (Spring),

maturity and marriage (Summer), middle-age and mid-life crisis

(Autumn), to death (Winter). The immediate post-war years were

not propitious ones for such subject matter (it had only 19 performances

over two seasons whereas his two earlier ballets had 37 between

them). Also choreographer Robert Helpmann infused little traditional

choreography into the ballet (whose audiences are tough to please).

The composer suffered a considerable disappointment with the reception

of this work. Nevertheless, the music remains highly attractive

(especially the Night Club Scene), especially in the hands of

its dedicatee Constant Lambert. Lambert’s reputation as a conductor

has always been high but is further vindicated in this world premiere

broadcast of half the ballet (ten numbers). One can imagine listening

to the wireless on that Spring evening over half a century ago.

Christopher Fifield

Ian Lace adds:-

I endorse everything that Christopher Fifield

says about this performance. Solomon and The New York players

under Boult give an exciting, inspired performance of this tremendously

difficult work. The later Solomon wartime recording of this Concerto

with a Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra comprising tired, ageing

payers (younger more vital performers had been called up for service)

is but a pale comparison. Playing devil’s advocate, I would not

go so far as to say, as Christopher does that the hiss and crackle

[and I would add, the sometimes furry, congested sound] on this

recording "adds flavour to the historical context."

I spoke to Bryan Crimp and he assured me he had done everything

he could to clean up the original acetate disc recordings but

the deterioration had been so severe that nothing further could

be done. I advise less patient listeners to persevere, for repeated

hearings only serve to confirm Bryan’s wise resolution to preserve

this extraordinarily powerful performance as a vital historic

document.

Equally important is the preservation of Constant

Lambert’s vibrant reading of Adam Zero in much better sound except

in ‘Dance with Death’. Lambert certainly knew a thing or two about

conducting music for dancing, music for the ballet!

Never mind the quality of the sound in the Concerto,

you will probably never hear more exciting accounts of these vibrant

and dramatic works.

Ian Lace