A mouth-watering prospect with a mix of familiar and

(currently) less familiar singers, with a conductor not immediately

associated with this opera, and crowned by a top-flight orchestra and

chorus. Sadly not everyone or everything lives up to expectations.

Aida (an opera which really does need no introduction),

has a cruel start for the orchestral violins, much like Wagner’s Lohengrin,

high up on the E string, but it’s pretty evident there’s no cause for

concern as far as intonation is concerned. It is not, however, too long

(the second track duet between Ramfis and Radames) before one realises,

Ah yes Harnoncourt, no vibrato and gut strings etc, the world of authenticity,

yet somehow (and thankfully so) thereafter the glossy bloom of the Vienna

Philharmonic’s strings starts to appear, whether deliberately or not,

to create that mystical impressionism which Verdi conjures. On the other

(less subtle) hand the brass is always glorious, burnished, blazing

especially in all those fanfares in the famous Triumphal March (for

this recording, which arises from the 1997 Zurich production, Harnoncourt

had specially made-to-measure ‘Egyptian’ trumpets), which anticipates

the four extra trumpets in the Requiem three years later. Harnoncourt

has no trouble whipping them to a frenzy in ‘Guerra’ guerra’. Fortunately

his tempi are traditional and not rushed.

The chorus enters into the Middle Eastern spirit of

the spectacle, not only in the grand climaxes. They also take on the

roles of priestesses and monastic-sounding priests with harp and solo

high priestess, producing a cohesively blended sound and distinctly

articulated text. Apart from a stodgy bass line (not helped by Harnoncourt’s

inflexible tempo), the famous Triumphal March is stylishly sung. The

ensuing sacred dance has a sexily sinuous ebb and flow (no doubt inducing

cobras to emerge from their baskets), its rubato flavouring the Egyptian

idiom with a dash of Johann Strauss (with whose music the VPO are in

their natural habitat). Harnoncourt over-stresses to a huge degree the

pp and ppp marks, which are more frequently found in this score, more

than many conductors have hitherto bothered to observe. However when

the dynamic range rises above forte, balance favours the (glorious)

orchestra more than the singers - not a wise move for opera. But Aida

was conceived as, and is, a grand spectacle so those dances and interludes

(which often feature glorious harp playing ) are given the full treatment.

The tenor Radames, like those violins, has a similar

straight-in-the-deep-end start with the famous aria ‘Celeste Aida’ to

cope with. Frankly Vincenzo La Scola only just makes it. With a singer’s

high notes one always, as a listener, has to feel that there is another

unsung higher note in reserve. With La Scola it takes an awful lot of

effort to produce the heroic goods. In ensembles he fares much better,

perhaps more confident with the support of other voices around him.

It’s all there, and generally he proves himself worthy of selection,

but it does not always sound comfortable (another example occurs in

his act three duet with Aida at yet another top Bb, a note every Italian

tenor should have with room to spare), and that creates unease with

any listener. On the other hand Olga Borodina, as the scorned but deeply

human Amneris, has no such limitations and paints her Verdian tone with

Russian dark-hued colours in an authoritative interpretation. Her approach

quite rightly dominates the second act, plaintive at first, then passionately

threatening in her confrontation with Aida. In the title role the Chilean

soprano Christina Gallardo-Domâs is a real find, and like Radames,

she has to put her marker down as a singer in the first act with ‘Ritorna

vincitor’. After a hint of uncertainty it develops into a scena which

she exploits to the full. This is glorious singing which, once it gets

into its stride, blossoms throughout the recording, and is particularly

impressive in the set ensembles which she rides with consummate ease.

She is beautifully tender in the Nile Scene, though the accompanying

oboe has a hint of reed trouble getting those final low Ds and a C to

‘speak’. Strangely at this point Verdi does not use the cor anglais,

which is a part of the opera’s exotic orchestration. One example of

this (and duly given much prominence by Harnoncourt) is the colourful,

almost Wagnerian (Tristan) combination of cor anglais and bass

clarinet in the dramatically critical scene (Act Four, Scene One) in

which Amneris desperately pleads her love to Radames. Verdi’s incredible

sense of orchestral colour is illustrated by the long solo for the double

basses introducing the Judgement Scene, which instruments he uses once

again as Otello creeps stealthily into Desdemona’s bedroom. The final

entombing scene produces touching moments from both singers.

Matti Salminen as Ramfis is, like La Scola, sometimes

put on the rack at the top of his voice, whereas the lower range is

stylish. There’s a brilliant sense of frustration each time he comes

to his third cry of ‘Radames’ in the Judgement Scene, and he whips up

his offstage priests to a frenzy, much to Amneris’s distress (another

glorious Borodina scene). Thomas Hampson may be unlikely casting for

Amonasro, but he fully lives up to his fine reputation, characterising

with initial humility, then intensely directed venom in the third act

duet with daughter Aida (Gallardo-Domâs continuing her fine singing).

This is followed by a transformation as he refocuses his desire for

revenge into impassioned patriotism for Ethiopia. In Amonasro one senses

the characters of Iago and Ford still to come in Verdi’s next and last

two operas. Last but not least, the King of Egypt, so often stuck away,

high up on a throne at the top of a ceremonial staircase, distantly

sounding like a bluebottle trapped in a jam jar, but fortunately not

here. Laszló Polgár has a fine regal tone and is another

artist with vocal presence and dignity, and he and fellow bass Salminen

together make an ideal combination.

On balance this is an excellent recording, some occasional

vocal reservations amongst some of the men maybe, but all worthwhile

for the singing of the two principal women, and for the fine orchestral

work throughout.

Christopher Fifield

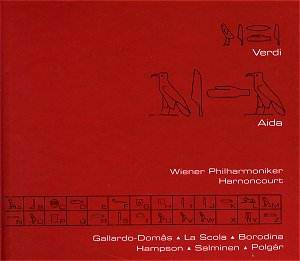

![]() Aida - Christina Gallardo-Domâs

(soprano)

Aida - Christina Gallardo-Domâs

(soprano) ![]() TELDEC 8573-85402- 2

[159.01]

TELDEC 8573-85402- 2

[159.01]