Although apparently a "difficult", elusive

work, Debussyís intentions and his own realisation of them in music

are so crystal clear that Pelléas et Mélisande

has had a long and distinguished discography from the Désormière

of 1941 through Ansermet and Cluytens down to Dutoit and others of recent

vintage with scarcely a dud one along the way. By and large the work

has remained in the hands of French interpreters or non-French who have

made a particular speciality of French music, and recordings have remained

in the tradition of that first Désormière performance,

most of whose interpreters had roots going back to Debussy himself.

Two recordings remain outside tradition and can be compared only to

themselves. One, oddly enough, is conducted by a Frenchman, the ultra-modernist

Pierre Boulez; the other is the present set under Karajan.

In Karajanís vast but rather selective repertoire a

small core of Debussyís works, principally La Mer and Prélude

à líaprès-midi díun faune, remained at the heart of

his affections and he returned to them again and again. He conducted

notable performances of Pelléas at La Scala in 1954 and

the Vienna State Opera in 1962, but this was his only recording of it.

While it is true that you will not find here the fruity tones of

the typical French woodwind, it is also true that Debussyís orchestral

writing can only gain from a conductor whose control over the sonorities

and the phrasing of his orchestra was on a level of mastery with that

which Gieseking and Michelangeli could obtain from their pianos. Instruments

waft in and out in a kaleidoscopic display in which perfection of ensemble

and perfection of balance are never made an end in themselves, for Karajanís

sense of the overall shape of the work, the long line, is unerring.

And let it not be thought that he swamps the piece in Wagnerian sonority,

for the bass-line is always light, the sound properly luminous and with

a real French mobility to the phrasing Ė he never lets things stagnate.

While the colours are predominantly sombre, he is acutely sensitive

to the occasional shafts of light that enter into Maeterlinckís shadowy

world, such as when Arkel hopes that now "un peu de joie et un

peu de soleil" will enter the castle; he also obtains playing of

searing passion in the interlude following Golaudís fearful outburst

"Une grande innocence", and his conducting of the opening

of Act V and its closing pages evinces his deep love of the music. Though

it is an unusual Pelléas, I did not find that Karajan

came between me and the composer at all.

The soft, crooning style of singing insisted upon by

Karajan in the more conversational passages (80% of the opera) places

a strain on the singers, but they all cope beautifully. It is indeed

strange to hear one of the richest-toned Verdian basses of his time

singing sotto voce, but Raimondi proves an inspired choice as

Arkel, his tone acquiring real beauty in the more melodic phrases and

tremendous power on the few occasions when it is needed. Van Damís Arkel

is also a remarkable assumption, from the bewildered beginning to his

increasingly sinister, brooding presence (mirrored by the harsher timbres

Karajan draws from the orchestra). His account of the "Une grande

innocence" scene is terrifying and he shows much psychological

understanding of Golaudís clumsy, barely comprehending attempts at rapprochement

with dying Mélisande.

Richard Stilwell is occasionally husky in his earlier

scenes but finds much beauty of tone as his love for Mélisande

develops. Von Stade remains elusive, alternating straight, girlish tones

with a sometimes heavy vibrato, and finding a degree of focus towards

the end. But I think this is part of Karajanís intentions, since Mélisande

is herself so elusive, mysterious. Who she is and where she comes from

is never really clear. This performance points up strongly the way in

which Pelléasís more ardent declaration of love fails to elicit

more than an almost disembodied response, a gently whispered "Je

tíaime aussi". She replies to Pelléasís longer outbursts

with brief phrases and, when he says she is looking somewhere else she

replies that she was seeing him somewhere else. Maeterlinckís world

is full of shadowy symbols, but I would suggest that in a certain sense

she doesnít exist at all, except as a reflection of what three lonely

men (and a lonely child) living in a dark isolated castle felt they

needed. Von Stadeís selflessness in accepting to sing an entire opera

without once putting her voice on display is rewarded by the fact that

she becomes the still centre of the opera even as Golaud is its dramatic

centre.

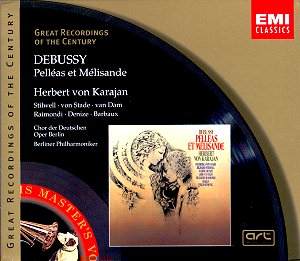

When a recording is issued in a series called "Great

Recordings of the Century", one is bound to ask, "is

it one of the great recordings?" For many of the generation that

grew up in a musical world dominated by Herbert von Karajan, the image

of the chromium-plated maestro producing ever more glossy re-recordings

of the standard repertoire proved eminently resistible. Strangely enough,

it was often his one-offs that revealed his greatness. Almost more than

any other recording of his that I know, this Pelléas is

one that I feel can be produced as evidence that (and the admission

almost sticks in my throat) he truly was a very great musician indeed.

There is a full libretto, a synopsis and a useful note

by Richard Osborne, all in English, French and German, and the sound

quality is everything you could wish for.

Christopher Howell