After the success of Der Fliegende Hollander (The

Flying Dutchman), Wagner was convinced that legend must be

the source of his operatic material. For Tannhäuser, his

5th opera, he produced his own libretto based on 19th

Century medieval legends. After a disastrous première in Dresden

(1845), the work gained popularity and over the next ten years was performed

throughout Germany. During this time the composer made many amendments,

the final so called ‘Dresden’ version being eventually published in

1860.

Wagner was invited by Napoleon III to present the opera

in Paris, where it was customary to provide a ballet scene. The composer

took the opportunity to rewrite whole sections. The major result of

these changes was to enhance the role of Venus and extend the bacchanal,

providing an ideal opportunity for the required ballet. The première

of the Paris version was given in March 1861.

The various alteration made for, and after 1861, enabled

Wagner to move further away from ‘number’ opera towards his ideal of

music drama and involvement with the psychological states of his characters.

The solo line is often declamatory, and to allow the part of Tannhäuser

in particular to dominate the ensemble, Wagner needed a new breed of

tenor with a voice heavier than that in Italian opera – the heroic

or ‘heldentenor’ and henceforth this voice would be important in all

his works.

Tannhäuser is now accepted as one

of the great operas of the 19th Century and these days both

the ‘Dresden’ and ‘Paris’ versions are performed, albeit often with

the casting of the title role proving difficult. This recording is an

abridged ‘Paris’ version of the opera, with Act 2 Scene 3 omitted, together

with a reduced Act 3 and other minor cuts. The reductions were as suggested

by the musicologist and critic Earnest Newman. The cuts are not unduly

serious and none of the best known music is affected. Most importantly,

Act 1 is complete, allowing the inclusion of the most significant of

Wagner’s ‘Paris’ amendments to be included. It was first issued on thirty

six 78rpm sides by the Columbia Gramophone Company who, in 1927, had

made the first recordings from Bayreuth (excerpts from Parsifal),

returning the next year for extracts from Tristan und Isolde,

conducted by Karl Elmendorff. These recordings, like Tannhäuser,

were not of live performances but used the spacious empty Festspielhaus.

Following favourable reviews of the Parsifal and

Tristan recordings, Columbia determined to return in 1930 and

record the new production of Tannhäuser to be conducted

by the great Arturo Toscanini, with singers selected by him. However,

the maestro was contracted to Victor records (later RCA) and he was

unable to participate. Columbia turned to their own highly experienced

Wagnerian, Elmendorff.

Columbia’s accumulated technical expertise ensured

that the recording was, in its period, a marker and whose sonic qualities

are realised in this re-issue which, as for others in this Naxos series,

is realised by the remastering guru Ward Marston whose work has received

acclamation on both sides of the Atlantic. Certainly the orchestral

music in particular is superbly caught, being well balanced with the

voices; the whole in a forward clear acoustic that in many ways belies

its age.

One can only imagine how a Toscanini performance would

have differed from what we have. To my ears Elmendorff, without undue

haste, allows the music to unfold with full dramatic impact; long phrases

encompassed with elegance and no lack of vitality. With the orchestral

sound undistorted and clear, this is a major plus point for the set

although there are times when the voices get close to distortion. Surface

noise is not evident nor are significant variations in level. Of the

singers, four were making their Bayreuth debuts in this production.

For the role of the eponymous hero, Toscanini had chosen the Hungarian

Sigismund Pilinsky (1891-1957). He sang for only two seasons at Bayreuth.

His strong, essentially lyric tenor of pleasing tone and diction is

certainly no heldentenor and there are times when his lack of vocal

heft is audible, albeit that the strain is never unmusical or ugly.

The Venus is sung by Ruth Jost-Arden (1899-1965), again chosen by Toscanini.

She later sang Isolde, Brunnhilde, Kundry, Electra and Salome. She also

appeared in Paris, Milan and New York. The part is nowadays usually

cast for a dramatic mezzo with a full tone and high top. Jost-Arden’s

bright fresh-toned dramatic soprano, caught before any deleterious effects

of the heavier roles, makes an interesting contrast. She has good breath

control, adequate power and a fine legato line, although ultimately

she lacks the ideal seductive tone the Paris version, in particular,

calls for. The Elisabeth is the soprano Maria Muller (1898-1958) who

appeared at the New York Met. (1925-35) singing Mozart, Verdi, Strauss

as well as Wagner. She also appeared in Berlin, Covent Garden, Milan

and Paris. Her clear lyric soprano, warm and vibrant, is ideally suited

to the part, a good vocal actress she conveys the emotions of the part

to near perfection.

Both the lower voiced men are cast from strength. Ivar

Andrésan (1896-1940) sings the Herman. He sang 10 seasons at

Bayreth (1927-36) as well as Wagnerian roles internationally. His beautiful

sonorous, noble sounding voice is heard to good effect here (CD1 tk11).

Likewise the Wolfram of Herbert Janssen (1892-1965): he made his debut

at the Berlin Staatsoper in 1992 and sang there until 1938 when he went

to the USA, singing in the Met from 1939-51. He was greatly admired

as Amfortas, Wolfram, Gunther and Kurwenal, all of which he sang at

Bayreuth, Covent Garden and the Met. With a warm sympathetic baritone

he deserved international success as preserved here. All the smaller

parts are well taken. Of particular note is the Hirt (shepherd boy)

of Erna Berger (CD1 tk2) where her pure tone and even legato are well

caught and indicative of the career to come.

The issue is accompanied by a leaflet with a track-related

synopsis and brief notes on the recording and the singers.

Robert J Farr

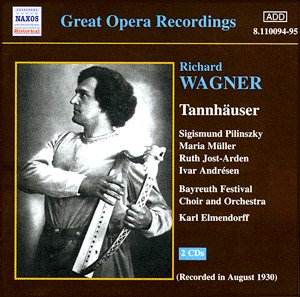

![]() Sigismund Pilinszky (ten)

(Tannhäuser), Maria Müller (sop) (Elisabeth), Ruth Jost-Arden

(sop) (Venus), Ivar Andrésen (bass) (Wolfram)

Sigismund Pilinszky (ten)

(Tannhäuser), Maria Müller (sop) (Elisabeth), Ruth Jost-Arden

(sop) (Venus), Ivar Andrésen (bass) (Wolfram) ![]() NAXOS HISTORICAL 8.110094/95

ADD [CD1 74.04 CD2 78.20] superbudget

NAXOS HISTORICAL 8.110094/95

ADD [CD1 74.04 CD2 78.20] superbudget