Leinsdorf’s reading of Verdi’s mighty Requiem is a

fascinating but ultimately flawed document. Recorded in 1964/5 and issued

on RCA SER5537/8, it had to shape up against the impressive credentials

of Giulini’s famous and visionary reading with the Philharmonia Orchestra.

RCA’s ‘Living Stereo’ recording sounds dated now, to be sure, but there

is no doubting the fact that its immediacy adds to the impressive effect,

even if the stereo separation is generally too pronounced.

One of the first things which surprises about this

performance is that the soloists sound so well matched (try the ‘Quid

sum miser’ section of the ‘Dies Irae’, or the exposed octaves in the

‘Agnus Dei’), something one would not immediately expect given such

a conglomeration of large vocal personalities. This means that whilst

each of them is more than capable of announcing their presence, they

work well together for the greater good. Bergonzi’s entrance five minutes

in to the first section (‘Reqiuem and Kyrie’) is neither reverential

nor religiously fervent. Rather, it is a statement of quasi-operatic

intent. Nilsson, entering a little later, is more than happy to match

him. Later, she positively relishes the opportunities to float up to

the higher registers. Lili Chookasian possesses a creamy mezzo, heard

to excellent effect in the ‘Recordare’, where she is truly tender in

Verdi’s best fashion.

The Boston Pro Musica Chorus has its work cut out in

this piece, and the Boston Symphony Orchestra does not seem in the mood

to make any concessions to volume. As a result, there is a hint of strain

from the choir in the almighty ‘Dies irae’ as they struggle to rise

above the wave of brass (and again in the ‘Tuba mirum’). Overall, there

is little serious fault from either soloists or choir. Perhaps where

this account falls short is the conductor’s vision. It is like listening

to an admittedly very well evoked series of well-paced and always graphically

painted dramatic excerpts, rather than a cogent whole that can in the

right hands be overwhelming in effect.

The two fillers for the second disc originally made

up one LP (RCA SB6609). Indeed, the Menotti may well provide the impetus

for the curious at heart to purchase this set. Universally known for

Amahl and the Night Visitors, The Death of the Bishop of Brindisi

(premiered in 1963) is another piece that centres on the innocence of

youth. This time, the Bishop of Brindisi relives the departure of a

crusade of children who were intent on reaching the Holy Land to free

the Holy City, and their cruel fate. Menotti’s style is effective because

of its very simplicity, his harmonies at once appealing and poignant.

George London makes an appropriately anguished priest, and the children’s

chorus is exceptional.

The rich, lush outpourings of the two excerpts from

Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder act as the ideal foil to Menotti’s world.

In some ways the Schoenberg is the highlight of the set. Leinsdorf elicits

crystal clarity from his forces (no mean feat in this work) and Chookasian

reinforces the positive impressions she made in the Requiem. She places

her high notes quite beautifully and, impressively, avoids excessive

vibrato.

Certainly, despite impressive moments, Leinsdorf’s

Verdi Requiem could in no circumstances be a top recommendation. Although

it contains much of interest, the Menotti is a fascinating and unusual

bonus, and full text is included.

Colin Clarke

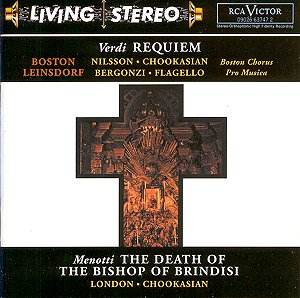

![]() aBirgit Nilsson

(soprano); Lili Chookasian (mezzo); aCarlo Bergonzi (tenor);

aEzio Flagello, bGeorge London (basses); aBoston

Pro Musica; bNew England Conservatory Chorus; bMembers

of the Catholic Memorial and St. Joseph’s High School Glee Clubs; Boston

Symphony Orchestra/Erich Leinsdorf.

aBirgit Nilsson

(soprano); Lili Chookasian (mezzo); aCarlo Bergonzi (tenor);

aEzio Flagello, bGeorge London (basses); aBoston

Pro Musica; bNew England Conservatory Chorus; bMembers

of the Catholic Memorial and St. Joseph’s High School Glee Clubs; Boston

Symphony Orchestra/Erich Leinsdorf. ![]() RCA VICTOR

LIVING STEREO 09026 63747-2 [two discs] [130.35]

RCA VICTOR

LIVING STEREO 09026 63747-2 [two discs] [130.35]