The Twentieth Century's harvest of music yielded variety

greater than that provided by any other century.

In the field of piano music the century moved from

widespread technical literacy to a small field of celebrity players

whose art is experienced in concert and on various forms of sound carrier.

At the start of the century learning the piano was one of the necessary

social accomplishments in most of the so-called civilised world. Now,

just into the new millennium, few learn the instrument as a social skill.

If it is learnt it is with a view to a musical career.

The variety of music encompassed by the century ran

from Ketèlbey, Joplin, Mayerl and Confrey through to Godowsky,

Holbrooke, Bliss, Bax, R S Coke, Lionel Sainsbury and Medtner in the

middle ground to the severity, danger and profusion of Shostakovich,

Sorabji, Ronald Stevenson, Howard Ferguson, Czeslaw Marek, John Foulds

and Malcolm Macdonald.

In the wilder extremities we encounter experimentalists

like Cage, Stockhausen, Ornstein, Henry Cowell and Conlon Nancarrow

whose preludes for prepared player-piano are far too little known and

remain beautiful despite the 'mechanical' element.

The Nordic countries have not, in general, been thought

of as originators of fine piano music. Grieg, Palmgren, Sinding and,

more up to date, Rosenberg are exceptions. Sibelius wrote plenty as

the lumbering but valuable BIS, Continuum and Naxos cycles prove but

the best of Sibelius is not for the keyboard although Kyllikki has

its moments as Glenn Gould proved in his CBS recording.

For those who know of Eduard Tubin, the Estonian composer

exiled to Sweden, his fame rests on his symphonies of which there are

ten and the stub of an eleventh. Vardo Rumessen, long an active ambassador

for Estonian music, is president of the International Tubin Society.

A pianist of world rank he has put a global career to one side and instead

has promoted Estonian music with a vigour and luminous advocacy matched

by an outstanding intellectual and artistic reach.

The first disc announces itself with the Six

Preludes - products of the Estonian years (1927-35). They range

through Debussian grave beauty (Jardin sous la pluie) in Nos.

1 and 2 to grave beauty to the haunted Baxian hill-song of No. 3 and

spring-like freshness of 4 and 5 (the latter a joyous walking song)

to the militant sourness of No. 6.

The Sonatina No. 1 is his first large-scale

work at 32.20. It was written in Heino Eller's class. Four movements

were written but only three survived. The first is a big span of splintery

grandeur - Chopin into Rachmaninov - lively with pearly filigree. It

was sold by the composer as a separate work. The second movement is

a rollicking dark scherzo. The andante mesto is highly romantic

standing apart from the impressionistic tendency of the preludes.

Hallilaul (1925) is virtually a prelude

in oils of Nordic impressionism. The Album Leaf (1926)

is a simpler version of the preludes. The Three Pieces for Children

(1935) are out of a Petrushkan music box. Similarly inclined

is the sturdy little March for Rana (1978). The Three

Estonian Folk Dances whisk us through a heavy-footed stomp via

a rustic whirl to a flat-footed distant shade of a birthday song. The

Prelude No. 1 (1949) exudes an exhausted and malign smile with

desperate business in hand followed by a trudge and finished by a single

downward slashing figure.

Folk music was a strong current in Tubin's music as

is evident from the 1945 Variations on an Estonian Folk Tune (1945,

rev 1981) [11.54] which is highly coloured and exciting, running ragged

variations on two folk tunes and achieving a splendid tragic nobility.

The Ballade on a theme by Mart Saar (1945)

[10.12] is on Saar's choral song Seven Moss Clad Tombs. It was

written in Stockholm. Archaic gravity swings this bell-swung piece.

Its grim jaw-set is like that of the 1949 prelude - not at all soft-edged.

This is a Bardic oration ending with typically Rachmaninovian austere

sweep.

The Four Folk Songs from My Country [15.06]

are from 1947. The carefree music-box rondel of the first does not prepare

the listener for the darkened goblin paths of the second song linked

as it is with his music for the Kratt ballet. The Polka of

the third has many a rustic hiccup as well as the dissonant pepper of

the Estonian zither. The final section rises to a craggy splendour out

of dissonance and a medley of rhythmic disruption.

The Sonatina No. 1 began life as a Sonata. Its

pith and marrow is from hyper-romantic genetic material flooded with

flourishes and nobility. The work opens up a new acreage of repertoire

where Rachmaninov could be rested and instead works like this and the

preludes of Tobias, Tubin and Eller would be lofted high alongside works

such as the Lionel Sainsbury Preludes. The Sonatina stands midstream

between Tubin's sonatas 1 and 2. Expression becomes more awkward in

the second movement but this is still a highly romantic apparatus. The

movement ends as if at a bier-side. The presto cuts a Gallic dash and

a lighter mood than you associate with the Tubin of the cold notes.

He soon reasserts himself in echoing stone, the play of ice and the

crackle of fire.

The third CD opens with Seven Preludes (1976)

[14.34]. The score is marked 'Handen, October 1976'. These works were

premiered by Rumessen in June 1977. The second is clearly influenced

by the grotesquerie of Shostakovich in which Tubin mixes a shimmer which,

to me, suggests the Northern Lights. The petulant Third Prelude's argumentative

impatience gives way to the resolute and terse Fourth. The Fifth is

based on an Estonian tune which shimmies like a North African melody

and develops in directions which are hard and joyous. The finale uses

a chaconne - a favourite device - developing an impressive defiance.

The seven part Suite on Estonian Shepherd Melodies

(1959) takes us through many transformations from lonely eminence,

Prokofievian shatter, to the impressionistic wash of the rain. This

is writing which seems to shadow the filigree of Godowsky's Java

Suite and of Bax's Winter Legends. The movements are very

brief. The final andante wanders dreamy classical pastures in

the same sun-dazzled mood found in Bantock's Pagan Symphony. Many

Scandinavian composers empathised with a classical Mediterranean Elysium.

The Second Sonata [25.08] is separated by twenty-two

years from the First Sonata and has 4pp of the booklet devoted to it.

The first movement's feathery dashing glitter has a touch or ten of

cold inhumanity. The swirling winds of conflict are typically Nordic

like Nystroem's storms in Iskavet. Other composers are recalled:

Ornstein's gales of notes, Mossolov's dexterity, Prokofiev's steely

wartime sonatas. The accessibility of the music is let in by Tubin's

Rachmaninovian accent discernible among stone-hewn flurries and dark

matters suggestive of John Ireland's Ballade. The cold Lapp tunes

of the second movement chart the far side of Saturn or Holst's cold

Betelgeuse with awkward fistfuls of notes. The iron-shod Prokofiev

hammering of the wartime sonatas returns in the third movement with

the shimmering aurora borealis cold, supernal and threatening

in its disconnection from humanity. This Sonata should be taken up by

Mark Gasser whose staggering performance of Ronald Stevenson's Passacagalia

on DSCH is available from him at mark@piano.freeserve.co.uk or by

Raymond Clarke, Murray Mclachlan or Marc-André Hamelin.

The booklet is 84 pages long with notes in English,

French and German. The English version covers 20 pages. It is delightfully

crowded with pictures of the composer and includes forty music exx.

There is no feeling anywhere in the collection that

Rumessen or BIS are going through a routine exercise. There is nothing

of the feeling of the dutiful surface skating evident in some 'complete

works' sets.

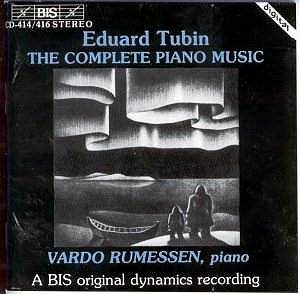

The cover of the CD features a 1973 mezzotint Norrskenet

(Northern Lights), Kaljo Pollu.

No collection already including the piano music of

Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Marek, Stevenson or Sorabji is complete without

this set. The music ranges through various gradations from pleasantrie

to a hard-eyed and intelligent romanticism.

![]() Vardo Rumessen (piano)

Vardo Rumessen (piano)

![]() BIS-CD-414/416 [180.10]

BIS-CD-414/416 [180.10]