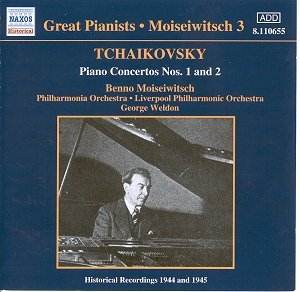

This is the third disc in the Naxos Moiseiwitsch series.

Moiseiwitsch (1890+1963) is represented in performances likely to be

well beloved of the 1940s generations with recordings made in two bombed

British cities.

The First Concerto is usually played for its corruscating

glint and keyboard strafing pianism. Moiseiwitsch was having none of

this. Instead we get a steady, reliable and really rather unemphatic

approach with poetic sensibility to the fore. Weldon and his orchestra

(not his usual one) make tender play with the andante but many will

miss the barn and the storm. Weldon gips things up in the finale but

the soloist is not tempted. Those brought up on Ogdon, Horowitz, Weissenburg

and Argerich will feel that there is something missing. I love the Viktoria

Postnikova version; the one with the Vienna Symphony conducted by Rozhdestvensky.

This is on the cheap Eloquence label.

The Second Concerto, disdained by most virtuosos, is

given, as was customary for the times, in the Siloti edition drastically

machete-ed to about 55% of the length of the work we hear now. I have

always thought of it as a sort of 'Coronation' concerto, regal and with

infusions of Beethoven and Mozart (revered by Tchaikovsky) and premonitions

of Saint-Saens. Alexander Siloti never secured the composer's permission

for his wholesale hatchet job.

Moiseiwitsch becomes much more animated in the finale

to the Second Concerto. However, overall this is the material of historic

documentation and Moiseiwitsch completism. To get a better handle on

the Second and at fuller length try Peter Donohoe or Emil Gilels (like

Moiseiwitsch born in Odessa) - both EMI. I am not sure whether Shura

Cherkassky's 1950s DG recording is still in the Universal catalogue.

Going by the liner essay the lack of gaudy sheen was

temperamentally in step with Moiseiwitsch's character which was transformed

by his divorce in 1924 from the Australian violinist, Daisy Kennedy

and by the death of his second wife, Anita, in the late 1930s. In his

leonine youth this was the man whose Chopin Revolutionary Etude was

in the late 1900s slated by Leschetizky for ostentation! Not much of

that here.

The surface burble is not hidden by Ward Marston's

audio restoration. Side changes are sometimes evident from the different

tenor of the softly insistent aural 'gruffle'. Everything is in mono,

of course. The piano sound is good for its age with no shatter; just

a slightly 'hooded' tone. Notes (English only) are by Nalen Anthoni.

Rob Barnett

![]() Benno Moiseiwitsch (piano)

Benno Moiseiwitsch (piano)

![]() NAXOS Historical 8.110655

[67.52]

NAXOS Historical 8.110655

[67.52]