I must confess straight away that these piano works

are novelties to me. Let me hasten to add that I did know of their existence,

but somehow I have never had the opportunity to hear them in either

the recital room or on a recording. I would suggest that the same applies

to many listeners; none but the cognoscenti will be familiar with these

early works. Of course most people's familiarity with Richard Strauss

will probably be through either his operas or his tone poems. If, like

me, one's first encounter with the master was the music from the film

2001 - A Space Odyssey, the tone poems will figure large in one's

estimation of his musical genius. Many opera enthusiasts will be taken

by Salome, Der Rosenkavalier and Ariadne auf Naxos.

However in recent years there has sprung up a whole

industry of 'Unknown Strauss'. A number of CDs have been issued which

explore some very esoteric territory indeed. And this is all to the

good. It is never sufficient to judge a composer on the few works that

seem to manage to feature on Classic FM or the popular classical CD

charts.

The piano works are unique. Although there appears

to have been a fair number of pieces composed over the years (Von Asow'

s catalogue enumerates twenty or thirty individual works) the normal

catalogue includes only half a dozen. The earliest surviving work by

Master Strauss is the 'Schneider Polka' (1870) written when the

composer was aged six. It would be nice to have it 'on the record.'

It is fair to say that none of the piano pieces in

Von Asow's catalogue or on this present CD will ever become well known

to the majority of listeners. However, it is encouraging to see Danacord

taking the risk in producing what is a very attractive disc. Every so

often it is good to move away from the core repertoire into uncharted

waters.

All that being said, there are dangers in resuscitating

early works. The works on this CD were composed when Richard Strauss

was in his teens. There is a potential mistake that listeners can make

in assuming that the mature composer is somehow present in their juvenile

oeuvres. Of course it is good to know how a composer developed. It is

interesting to see what early potential he revealed - perhaps even spot

a characteristic harmony or melodic interval. However, early works can

often disappoint. They are often written in different and diverse styles

- unrelated to what has become familiar in the composer's mature writings.

Influences are apparent which the composer may later disown. The pupil

can often create works in the teacher's image.

What I want to emphasise - and it is important for

much music - is that early works can be good in their own right. This

is true even if they are to a certain extent pastiche.

So what is the listening strategy we should apply to

these works? The first thing to get over is that much of this music

is like Mendelssohn. But I say 'So what!'

The great master had died some 35 years before Strauss's

birth and was still hugely influential. He was well played both in the

recital rooms and in private salons and drawing rooms. Although Richard

was a violinist, he could play the piano. The 'Songs without Words'

would have been a regular companion to all neophytes in those days.

So we must try simply to enjoy the music, as it is;

not grumble about what it could have been. It is not fair to apply the

canons of criticism to a sixteen-year-old boy that would be relevant

to a man four times his age. The bottom line is - Do we enjoy this music?

If No, then so be it. If Yes then great!

At first glance we seem to have little against which

to judge Strauss's ability to write for piano: the present three works

plus a few more unpublished works. But we are in danger of forgetting

the 200 or so songs - all of which have excellent piano accompaniments.

Even a cursory glance at these songs will reveal a composer who understood

the piano and wrote for it in an accomplished and technically competent

manner.

The earliest work recorded on this disc is the Five

Piano Pieces Op. 3. These are of quite considerable length; the

longest being some eight minutes! They are hardly miniatures. The music

is full of the spirit of Mendelssohn, Weber and Beethoven. The opening

number is a quiet Andante - a genuine 'song without words'. Yet

somehow it seems just that little bit different - there is something

intangible here. It is a lovely reflective piece that would go down

well in any recital. The second piece is a scherzo or a scherzino, which

hardly ever seems to get going. There is a definite touch of the Midsummer's

Night's Dream about it. The Largo is a beautiful essay in

pure pianism. It is like the older master at his very best. This is

one of the loveliest pieces not in the repertoire. And

I think it is probably not too difficult - so there is no excuse. The

fourth piece is an Allegro Molto that seems to me to be rather

slow paced. The Allegro marcatissimo is perhaps the least successful

of these five pieces. It is a little march that has echoes of Bach's

Anna Magdalena Notebook.

The Sonata in B minor Op.5 is rather good. It

is a valuable and worthy addition to the literature of Romantic piano

music. Yet it is largely unknown to the vast majority of listeners and

probably recitalists too. It is rather like a lost sonata by Mendelssohn

suddenly turning up. And that is definitely no criticism.

The first movement is an Allegro Molto Appassionato.

This has some lovely intense figurations. Both the subjects are extremely

interesting. Both are well developed. However it is the dreamy second

subject that steals the show in this movement. Here and there we are

conscious of Liszt; again this is hardly surprising given the popularity

of that master in the late nineteenth century.

The Adagio Cantabile is another attractive 'song without

words'. It is completely in the style of Mendelssohn. It is perfectly

played here - with the limpid melody given prominence over the accompanying

figurations. This movement is probably well within the gift of the amateur

pianist. It is a perfect fusion of harmony, melody and form.

The Scherzo is once more influenced by the music of

the Midsummer Night's Dream. It is a well-constructed piece with

a rather wistful 'trio' section.

The last movement is perhaps the weakest of the four.

Saying this, it must be admitted that there are some interesting 'variations'

of the principle theme. And the second theme is rather good. Perhaps

its weakness is its similarity to the previous movement?

In spite of one or two reservations this is a good

sonata that well deserves an occasional airing in the concert hall and

on radio.

The Stimmungsbilder or Mood Paintings Op.9

are not just more examples of late nineteenth century salon music. They

are much better than this. The five pieces last a total of some twenty

minutes.

The first painting is subtitled - 'In silent forests'.

Forget the verbal imagery and just enjoy the music. This is a very delicate

piece - full of attractive pianistic writing. One perhaps becomes aware

that Richard Strauss is moving away from his models. There is something

fresh here.

'At the Spring' is definitely not based on the

fast flowing or spouting variety. It is quiet and gently bubbly and

rather peaceful; like a fountain in a summer garden. This is a truly

lovely piece.

The Intermezzo is a varied little work - with

lots of changes of mood. There are skittish moments in this piece, but

these are offset by more reflective passages. It is a good example of

the genre.

The 'Reverie' - is a character piece if ever

there was one. A little aimless, perhaps, this quiet restrained piece

is actually rather good.

The last of the five Mood Paintings is called

'The Heath.' In some ways it is almost Scriabinesque in its use

of harmonic colouring. Lots of bare fifths. This is an unusual piece

- but that does not deny its value.

Perhaps in these five pieces we are beginning to hear

Richard Strauss move away from his romantic models. It may be possible

to hear some intimations of things to come.

However the bottom line is that it really does not

matter. Enjoy these pieces for what they are- the competent works of

a young man about to embark on a career as one of the greatest composers

of the twentieth century.

The CD is well produced - the programme notes are adequate

bearing in mind that all these works are hardly a major part of the

composer's oeuvre.

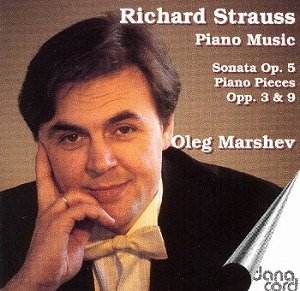

The playing is superb. Oleg Marshev takes these works

to heart and plays with enthusiasm and understanding.

One of Marshev's strength is that he is able to play

'lesser' works from the pianist's repertoire with conviction -as if

they really matter. And of course my contention is that they most certainly

do!

John France

![]() Oleg Marshev - piano

Oleg Marshev - piano ![]() OlegDANACORD DACOCD

440 [73.53]

OlegDANACORD DACOCD

440 [73.53]