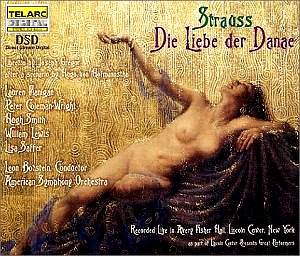

Der Liebe der Danae is hardly standard repertory

these days, so a good modern recording comes like a breath of fresh

air. The opera is, in short, delightful. Even the designation given

to it by the composer (‘a lively mythology in three acts’) reflects

this. Despite its subject matter, its world is more fairy-tale than

myth, a scenario which offers Strauss ample opportunities to reveal

the defter side of his compositional persona. This comes across particularly

in the orchestration, often gossamer-light and continuously shifting

in its colours.

The libretto is described as 'by Joseph Gregor, after

a Scenario by Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Der Liebe der Danae was

dedicated to Heinz Tietjen. The late 1930s were historically a dark

era in Germany, and this mythical world would have provided an ideal

escape. The scenario by Hofmannsthal originally dated from just after

Die Frau ohne Schatten (1919), but this was soon forgotten as

Strauss became preoccupied with Intermezzo. It was only in 1938

that he returned to Danae: Joseph Gregor was given the task of

working with Hofmannsthal’s sketch: the result may not have the greatness

of Hofmannsthal's finest work, but perhaps this only steers one's attention

towards Strauss’ glorious music.

The libretto works with two myths: Midas (whose touch

turns everything to gold) and Jupiter's appearance to Danae as golden

rain. Its message seems to centre on the supremacy of human love over

all obstacles: at the end of the opera, the ‘all-powerful’ god Jupiter

is left to ruminate to himself over the beauty of Danae and Midas’ love,

and his own shortcomings. Along with this comes the underlying idea

of the futility of materialism and its eventual subservience to human

love. Just the idealistic tonic to raise Strauss’ spirits, therefore.

The cast in the present recording is not one of superstars:

Peter Coleman-Wright may well be the only name familiar to listeners

this side of the pond, having appeared on discs from Hyperion and Chandos,

among others. Coleman-Wright actually takes on the most demanding role,

that of Jupiter, and is fully equipped with a powerful voice to do so.

His final acceptance of his lot, right at the close of the opera, is

a fitting climax to the plot and Coleman-Wright's interpretation gives

it all the requisite dramatic force. Nevertheless the overall power

of this performance comes less from individual performances than from

the cumulative effect of the ensemble as a whole. Initially, Lisa Saffer

as Xanthe seemed stronger than Lauren Flanigan's Danae, but Flanigan

seems to get better and better as the opera progresses. The Four Queens

at the beginning of Act Two work beautifully together. Hugh Smith's

assumption of the key role of Midas is generally persuasive (and at

his best he is excellent), but he has problems with lower notes and

this may become uncomfortable on repeated listenings. And repeated listening

is recommended in the case of this opera, as Strauss’ complex score

only delivers more and more as time goes on.

All of the subsidiary characters are taken at the very

least well by the cast here. The American Symphony Orchestra plays with

a combination of lyricism, playfulness and precision for Leon Botstein

(it is difficult to believe, from that aspect, that this is taken from

a live performance). This recording should be investigated post-haste

by any self-respecting Straussian, and makes for the ideal modern partner

to Clemens Kraus’ live performance with the Vienna Philharmonic on Orfeo

C292923D. Kraus also goes to the heart of this piece (and with a greater

orchestra), and boasts Paul Schöffler as Jupiter and Anneliese

Kupper in the title role.

Colin Clarke