With good orchestral playing and intelligent conducting

this Sibelius compilation has much to commend it. The Stockholm connection

has a strong tradition as far as this composer is concerned, including

the 1924 premiere of the Seventh Symphony, and the authenticity of the

orchestral sound world is never in doubt at any stage.

The recording too is clear and well focused, if cut

at a relatively low level. However, any reasonably good equipment can

provide the necessary boost, if domestic circumstances allow such a

thing. This was originally recorded for Finlandia in 1996, and is now

taken up by Warner Classics' Apex series.

Someone at Warner ought to have another look at the

design of the booklets for this series. Why have such tight-packed small

print on glossy paper when the whole of the back page of the four pages

is left entirely blank? It makes no sense.

As for the performances, any criticisms are on the

level of interpretation, by the listener as well as by the artists;

for anyone acquiring this disc can be guaranteed the satisfaction of

knowing that the music is well served. The climaxes build with a brooding

intensity that is thoroughly Sibelian, though occasionally, and particularly

in Tapiola, that intensity might have reached a darker power.

There is also a sense of structural control and the

longer term vision this implies. In this respect Tapiola goes very well;

here and elsewhere the tempi always seem right for the purpose. Of course

the field of recordings of this repertoire is very competitive, featuring

some real 'classics of the gramophone'. And it is no use pretending

that Davis matches Beecham in the nuances of texture and phrasing that

make such miraculous effect in The Oceanides. Beecham remains a clear

leader in this piece, partly because his recording from the late 1950s

still sounds so well. The word 'historical' need not apply on this occasion.

Sometimes the orchestral balances for Davis and the

Stockholm orchestra have a pallid feel, and the two most notable and

extended solos in these pieces both suffer in this regard. The great

cor anglais solo in The Swan of Tuonela is surely too recessed in the

perspective, with a resultant lack of brooding intensity. So too the

closing phase of En Saga allows too little of the clarinet's personality

to make its mark.

Such doubts need to be placed in the context, however,

of the thoughtful and sensitive performances of a true Sibelian.

Terry Barfoot

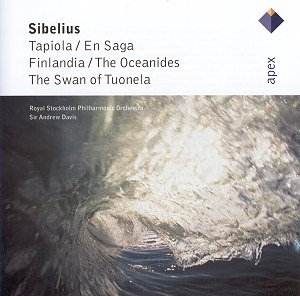

![]() Royal Stockholm Philharmonic

Orchestra/Sir Andrew Davis

Royal Stockholm Philharmonic

Orchestra/Sir Andrew Davis ![]() APEX 09274 06202 [75.48]

Budgetprice

APEX 09274 06202 [75.48]

Budgetprice