For Robert Planquette fate was a great provider.

Born in Paris on 31 July 1848, and of Norman origin, this son of a singer

was privileged to be in Duprato's class at the Paris Conservatoire.

He did not get much out of his studies, not least because he did not

finish them, preferring to exploit his talents as a café pianist

and tenor. A few romances brought less fame than did his song, Sambre

et Meuse, first sung in 1867 by Lucien Fougère, who went

on to be the glory of French opera stages. Before Les Cloches de

Corneville, Planquette had never before composed a full musical

score: for a first attempt it is nothing less than brilliant. The score

just flowed with sparkling melodies, variety of rhythm, novel orchestral

texture and bright colour. Throughout lovely motifs like the one representing

the Bells weave in and out of the music. It is said that Planquette

farmed out the orchestration to more competent musicians than himself.

If so, they made a good team: the chorus part-writing is particularly

fine in places. The style of composition changes considerably throughout

the piece and Planquette freely borrows from other composers. Listen

to the sumptuous Italianate chorus number ‘Silent Heroes’ (CD2

tk4), or Delibian barcarolle (CD1 tk.7) and duet (CD2 tk.8). (Delibes

had composed Coppélia seven years earlier and Sylvia

the year before this operetta.) Planquette’s skill in making melodies

blend and flow can be heard in the Act 1 finale (CD1 tk.20, first 4

mins) with its inventive rhythms and brilliant colour.

In 1876, the director of the Folies Dramatiques, a

fantastic talent-spotter, gave Planquette a commission to compose an

operetta which had originally been intended for Hervé on a libretto

by Louis Clairville and Charles Gabet, after a play by the latter. Les

Cloches de Corneville followed Offenbach's La Foire Saint-Laurent;

the first of his works to be given at the Folies-Dramatiques which had

a luke warm reception. Just as sad was the failure at the Bouffes-Parisiens

in November of Emmanuel Chabrier's L'Étoile, a true masterpiece,

which nevertheless never managed to find its public. This was hardly

the case with Les Cloches de Corneville when it was premièred

on 17 April 1877. The sprightly and sparkling music coupled with interesting

characterisations caused the piece to run for a generous 580 performances

and when translated into English and performed in London upstaged HMS

Pinafore by chalking up a staggering 708 performances. Its opening

production was carried by excellent performances from Ernest Vois (Henri

de Corneville), Milher (Gaspard), Simon Max (Grenicheux), Conchita Gélabert

(Germaine), and the very young Juliette Girard (Serpolette), who under

the name of Simone Girard went on to have a brilliant career. Later,

when records came in, famous comic actors like Fernand Ledoux and Daniel

Sorano were quick to cut a disc or two by taking up the character of

Gaspard.

Les Cloches de Corneville’s reputation

has survived, crossing several generations without difficulty, and it

was probably the most popular French operetta of all time. The story

has been criticised for being "plagiarized from ‘La Dame blanche’

and ‘Martha’ " (as Clement and 'Larousse's Dictionnaire des Operas'

deplores "the debased character of this work, which reflects exactly

the amount of wit, taste and art of the greater part of the French public

as formed, trained, modeled and perverted by the operetta.")

The plot and theatrical devices work well enough– a

supposedly haunted castle; an heir who comes back incognito; a young

girl abandoned in a field, who thinks she is a princess; a fake ghost

who is in fact a real old miser trying to profit from the riches of

his aged employer; a niece who isn't a niece but is an aristocrat –so

what more could a plot want? Add to that a dash of Gallic levity and

vibrant, well-crafted music and the pretty and undemanding essay in

counterpoint in the first-act finale (CD1 tk.20). Many of the songs

have long since passed into the common memory from Va petit mousse

to the Cider Song, by way of the Legend of the Bells and

the Marquis's waltz "I've been three times around the world".

Act 1 opens on a market day (or ‘fair day’ in the English

edition) in Corneville, a sedate town dominated by a castle whose owners,

having gone abroad, have never since shown any sign of life. Serpolette

acts as maid to Gaspard, an old skinflint who found her as a child abandoned

in a field of wild thyme–serpolets, hence her name. She is enamoured

of the fisherman, Grenicheux. Gaspard's niece, Germaine, whom Grenicheux

saved from drowning, has vowed to marry him, while her uncle intends

her to marry the Bailli. A stranger arrives, whom Germaine attempts

to turn away from the castle, saying it is haunted, and that its bells

will only ring the day its owner's heir returns. (The stranger is in

fact Henri de Corneville, the Marquis, who recalls his childhood and

a young girl who fell into the sea. He pulled her out and never saw

her again.) The market is now at its busiest. Henri takes Germaine,

Serpolette and Grenicheux into his service.

In Act 2, within the great hall of the castle, Henri

de Corneville, in the company of his retainers and villagers, discovers

a letter. It mentions that the Vicomtesse de Lucenay was at one time

in danger and so was entrusted to Gaspard to be brought up under a false

name. Everyone thinks this must be Serpolette. To Grenicheux, hiding

in a suit of armour, fails to resolve the mystery of the ghosts. He

ends up catching Gaspard, who thought up the hoax to frighten off strangers

in search of the riches of his former masters. The shock drives the

old man mad.

At the commencement of Act 3, the bells have

rung and Henri has been recognized as heir to the Castle of Corneville.

Grenicheux has become valet to the Vicomtesse Serpolette. But Henri's

memories have been stirred: the young girl who escaped death thanks

to him is Germaine. Grenicheux is nothing but a liar. Recovering his

senses, Gaspard declares that his pretended niece is in fact the true

Vicomtesse de Lucenay. Germaine will marry Marquis Henri, Serpolette

will rebuff Grenicheux, and from now the bells can ring whenever they

like.

This is a strong cast headed by Mady Mesplé

who with her characteristically light soprano voice and rapid vibrato

seems right for Germaine. She is well supported by the other soloists.

Christiane Stutzmann as Serpolette is a somewhat brittle soprano with

good diction. Her Rondeau (CD1 tk.5) is sung in a rather jerky staccato

fashion which sounds forced: although the accompaniment is marked staccato

this isn’t marked so in the singer’s line. Both Charles Burles (Grenicheux),

Bernard Sinclair (Henri de Corneville, the heir) give good support.

Burles gives a good performance in the charming and haunting barcarolle,

‘On billow rocking’ (CD1 tk.7) yet is slightly behind the beat

in the duet with Mesplé which follows (CD1 tk.9). Jean Giraudeau

(Le Bailli) sings his buffo song with good humour (CD2 tk.2). The baritone,

Jean-Christophe Beniot who has recorded in a number of this EMI series,

with pleasant timbre competently sings Gaspard, a key part. The orchestra

is pleasantly balanced and allows one to pick up the full colour and

nuances of the score. On the strength of this work it would have been

nice to hear how Planquette got on with a later equally good operetta,

Rip Van Winkle (1882) written for the London stage and later

translated into French as Rip. By all accounts it was highly

successful and well received. A 1961 recording of it does exist on Musidisc

(Harmonia Mundi) CD no. 20160-2 and should be well worth trying.

Of the EMI twelve reissues in this series, this set

carries the worst track indexing and listing. The speech often runs

over the initial or final bars of a number. This must have caused a

problem knowing where to place an index marker but things do not need

to be so bad. Sometimes a piece can even have its first few bars laid

on the previous track. Since clearly the dubbing of dialogue was done

after the music speech overhangs at the start of a number could have

been avoided (at the end of a number this doesn’t matter so much though

I think many listeners would prefer to hear the music uninterrupted).

With this mid-price issue, interesting brief notes

by Michel Parouty in French and English are included. The track listing

is in parts incomplete: tracks 26 and 27 on CD1 do not exist in the

booklet.

Raymond Walker

Further reading: "Operetta", Traubner (Oxford 1883); ‘Musicals",

Ganzl (Carlton 1995)

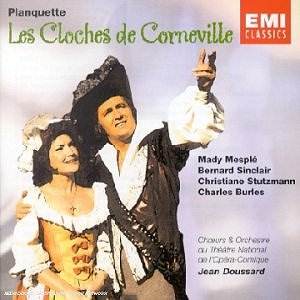

Pic. Poster taken from "Musicals" (Carlton 1995)

![]() Mady Mesplé (Germaine),

Christiane Stutzmann (Serpolette), Charles Burles (Grenicheux), Bernard

Sinclair (Henri de Corneville), Jean Giraudeau (Le Bailli), Jean-Christophe

Beniot (Gaspard)

Mady Mesplé (Germaine),

Christiane Stutzmann (Serpolette), Charles Burles (Grenicheux), Bernard

Sinclair (Henri de Corneville), Jean Giraudeau (Le Bailli), Jean-Christophe

Beniot (Gaspard) ![]() EMI 574 0912 [CD1

63.30 CD2 57.06] Midprice

EMI 574 0912 [CD1

63.30 CD2 57.06] Midprice