What a range of transfer techniques Naxos seem to be

using. Having praised their Moiseiwitch and protested vigorously about

their Schnabel (Beethoven Concertos 3-5), praise seems in order here

again. Some swish remains and it sounds a little as if Mark Obert-Thornís

method is simply to put the discs on a period player with a fibre needle

and record them like that. If so, there could be worse ways of doing

it. Beechamís orchestra sounds a little crumbly but the violin is somehow

lifted from the context and has a wonderful speaking quality. Strangely,

the slightly earlier Beethoven recording is better still, with fuller

orchestral sound. Though I was born well into the LP era, there were

still people around in the late fifties who had only 78 equipment (just

as some today have not yet got into CDs) and this is the 78 sound as

I remember it.

The career of Joseph Szigeti (1892-1973) lasted a little

too long for its own good and in my college days his name was a by-word

for slovenly, swoopy, portamento-ridden playing. In vain did our elders

and betters tell us that his playing was far different in his prime,

but, as can be heard here, our elders and betters were quite right.

In terms of portamenti thereís not much to offend

modern ears and I can think of some present-day practitioners who might

well use more, even in Mozart and Beethoven. When I said above that

the recording gives his violin a wonderful speaking quality, it was

implicit that this quality came first of all from the violinist, and

it is above all for the very human, vocal manner of his playing that

these performances are valuable. I was surprised to find Tully Potter,

in his informative notes, turning critic and commenting that "Truth

to tell, Beecham, the supposed Mozart lover, serves up an accompaniment

that is brusque in some places and slapdash in others". Frankly,

I could only find admiration for the lightness of touch which with which

Beecham supports Szigeti in tempi which (especially in the last movement)

could all too easily have lapsed into heaviness. I think the main theme

in the last movement really is too slow for an Allegro, for all the

performersí grace, but otherwise this is a beautiful performance.

Iím not so sure about the Beethoven. Certainly, Szigetiís

speaking quality gives a meaning to many passages where it sometimes

seems that the violinist is practising his arpeggios while the orchestra

plays a tune, but it doesnít quite all add up. Both Szigeti and Walter

change tempi fairly freely, not necessarily at the same points with

the result that the first movement appears to be a rather sprawling

structure. On the other hand, they do seem to respond to each other

at least on a phrase-by-phrase basis and the performance has the spontaneity

and humanity for which both artists were renowned. Perhaps it is better

to view this as a snapshot of a great violinist playing the Beethoven

rather than a great performance of the Beethoven.

Myths are funny things. There are some early recordings

which really do seem not to have been matched artistically since, there

myths which require imaginative listening to understand what the fuss

was really about, there are others again which donít confirm their legendary

status at all. This is really none of these. It would seem to suggest

that fine performances then and fine performances now were not so unrecognisably

different. "Great performers" in the popular mind is sometimes

synonymous with "dead performers". Yet a comparison of this

with recent versions by, say Perlman (to choose one out of many) would

tend to suggest there is more community and continuity of feeling between

the public of the 1930s and our own nearly three-quarters of a century

later than we might suppose. And itís marvellous that such well-sounding

recordings exist to prove the point.

Christopher Howell

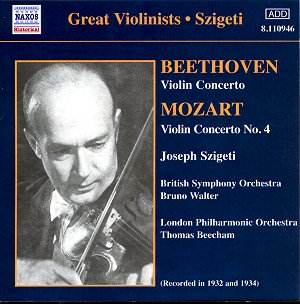

![]() Joseph SZIGETI (violin),

London Philharmonic Orch/Sir Thomas Beecham (1), British Symphony Orch/Bruno

Walter (2)

Joseph SZIGETI (violin),

London Philharmonic Orch/Sir Thomas Beecham (1), British Symphony Orch/Bruno

Walter (2) ![]() NAXOS Historical 8.110946

[66.56]

NAXOS Historical 8.110946

[66.56]