Though Iíve read reams on the tragedy of Mozartís early

death, I donít remember ever having heard or read the wish that he had

written more than he did. I think this reflects, not the fact that we

love him a little less than we say we do, but that we simply cannot cope

with all his output as it is.

Take all those Divertimenti and Serenades. The aristocratic

patrons of Mozart, Haydn and their lesser contemporaries expected to

be able to boast to their guests that new music was on offer that evening

and their musician-servants were expected to provide it. Not long ago

I was writing about Spontiniís first opera and commenting that Italians

went to the opera at the beginning of the 19th Century in

the same spirit as a later age went to the cinema. Writing these divertimenti

and the like was the 18th Century equivalent to composing

jingles for TV commercials and Mozart, with his sublime facility, could

churn them off better than any.

Except, of course, that Mozart never churned anything

off. Supposing the Divertimento here was one of a mere dozen of his

works to have survived. How we would wonder at it, analyse it. Every

note of it would be famous, its adagio would be celebrated as one of

the most divinely expressive pieces ever penned.

And, maybe, it would get performed with that burning

conviction that tends to be reserved for the pinnacles of the repertoire.

The Leopold String Trio are very, very good, no mistake about it, with

the sweet goodness of good musician friends who gather late at night

to enjoy making music for their own benefit, with no gallery to play

to, no public to make their points to. Or like a group of well-behaved,

civilised musicians playing in the corner of an aristocratic dining-room

while their social betters wine and dine. (Though even the hostess herself

might be imagined to pause as the trio to the second minuet enters,

her fork halfway between her plate and her mouth, to remark that the

music was very nice this evening; and perhaps again at the folk-like

simplicity of the finaleís main theme). Itís all a question of oneís

point of view, but mightnít they have been a little more outgoing, a

little more intent on engaging their public rather than just playing

to them? Still, they certainly respond to the great adagio.

The duo is one of two, thrown off (except, again, that

it was no such thing) to help out Haydnís younger brother Michael who

was too ill to get a commissioned set of six completed. Itís remarkable

what sonority Mozart can get out of just two instruments. If you want

to hear the disc straight through, I suggest programming this first.

Beautiful recording and detailed notes from Duncan

Druce in English, French and German.

Christopher Howell

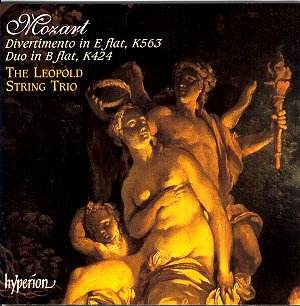

![]() HYPERION CDA67246 [67.27]

HYPERION CDA67246 [67.27]