If you are serious about Mahler you cannot take him

a la carte. You either take all of him, every major work from

his composing life, or nothing. Thatís my opinion, anyway. You think

itís a harsh one? Let me explain what I mean. I once received a letter

from someone who had read my survey of Mahler recordings. My correspondent

displayed great knowledge and love of many individual Mahler works.

Then came the parting comment: "So I do love Mahlerís music, though

I never listen to the Seventh or Eighth Symphonies. I canít take them

at all." I suggest that my correspondent has missed the point of

Mahler and so was consequently only possessed of a partial picture of

the man and therefore his work because Mahlerís symphonies are like

an eleven chapter autobiographical novel in music and to ignore two

of the symphonies is like ignoring two chapters in that autobiography,

leaving you with an incomplete portrait. Also, just like all great novels,

many of Mahlerís "chapters" carry significant references back

to previous "chapters" providing context and framing. None

more so than the Fourth Symphony which began life in the aftermath of

the completion of the Third. Crucially Mahler had originally planned

that his setting of the "Wunderhorn" poem "Das Himmlische

Leben" would be the final movement of that gigantic work. Hard

to believe, but there it is. As always, however, Mahler proved his own

best editor and perhaps responding to the subconscious urges that move

great creative artists he used the completed setting of the poem as

the starting point for his Fourth Symphony, even though he always saw

it as the last movement there also.

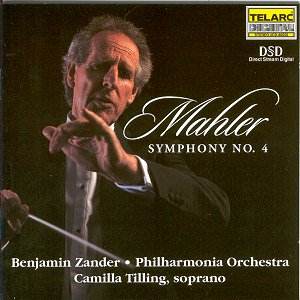

In the free discussion disc that comes with this new

release I found that Benjamin Zander lays the greatest stress on the

fact that in the Fourth Mahlerís end is also his beginning. However,

since I listened to Zanderís performance of the symphony before I listened

to the discussion disc I can honestly say that I knew this was his belief

anyway. Because, by some strange alchemy, Zander has managed to vividly

convey the last movement as the real culmination, the homecoming, for

the whole work and it is that that in the final analysis makes this

a satisfying recording to own. Indeed I have heard other recordings

where, in comparison to this one, it is almost as if the conductor is

rather embarrassed by such an apparently trite ending to such

a spacious work, especially following one of the greatest and most profound

slow movements Mahler ever wrote. As always with Mahler there is profundity

to be found in the most unlikely places and juxtapositions and it takes

a conductor who knows his Mahler intimately, as Zander does, to bring

this out emphatically. His soprano soloist, Camilla Tilling, is quite

charming. Far more the "tomboy" than many of her colleagues

and her contribution undoubtedly assists Zander in marking the performance

of this movement out as distinctive; though Iím sure she was also amenable

to Zanderís detailed coaching - something which might not have been

the case with a more established diva. Again, many otherwise

great recordings founder a little by casting a star soprano in the last

movement and by her conductorís inability to really coach her into the

kind of performance Tilling gives. Not a definitive one of course, but

newly thought enough to make you hear the music fresh, both on its own

and in its correct context. As if to further prove he has thought very

deeply about how this movement should be presented, in his discussion

disc Zander plays an extract from a concert performance of the work

that he conducted in Vienna where he used a boy soprano for the movement.

This has been done a couple of times on record (by Nanut and Bernstein)

but I have never been in favour of it for all kinds of reasons. Not

least the fact that Mahler asks for a soprano and not a treble. So Iím

glad Zander resisted the temptation to cast a boy in the recording,

as it must have crossed his mind to do so.

It is hard to know precisely how Zander conveys the

impression of the last movement as true culmination so well as he does.

Perhaps time and repeated hearings will reveal more. Reviewing new recordings

is sometimes about giving interim reports, trying to arrive at the kinds

of conclusions one has reached already about recordings lived with for

sometimes thirty years. Some of what Zander achieves in this instance

probably stems from the way he treats the preceding three movements

which, I have to say, on their own I do not find as convincing. But

that may well be part of the reason why the last movement does shine

so brightly when it finally comes. Perhaps itís all part of Zanderís

cunning master plan for the Fourth: stand back emotionally in the first

three movements so as to let the fourth blossom all the more. Or perhaps

the effect is arrived at more by luck than judgement, succeeding in

this particular instance in spite of everything. If that is so it isnít

intended as a criticism of Zander. In fact it could be construed as

a compliment with his own response to the music in front of him perhaps

coming from depths of which even he knows not. Since music above all

the arts works at the very deepest levels of our responses, interpreters

especially must be all too susceptible to certain urges to do one thing

rather than another without quite knowing why. Conscious or subconscious,

it hardly matters. The art of performance is a delicate and ephemeral

flower at the best of times, so when something clearly works itís not

essential to enquire too deeply into why it has come about. Letís just

enjoy the result.

In the first movement Zander appears suspended on the

cusp between neo-classical restraint and zeal to deliver surface lustre.

It certainly seems as though he is wary of crumbling the musicís petals

so that the movement emerges in a rather patrician fashion: all symphonic

and score details superbly attended to but lacking degrees of fallibility,

approachability. I donít think Zander is helped by the recorded

sound that I find a little too general and bass light to make a great

impact and deliver the musicís character. Contrast this with the Kletzki

recording on EMI or Royal Classics, for example. Even after all these

years this is still an object lesson in how to balance this work with

bags of detail in perfect proportion. The second movement is more persuasive

in both cases with Zander, though. Here he and his violin soloist, Christopher

Warren-Green, really have gone to some trouble to project the particular

fairy tale evil lurking behind "Friend Death". I liked too

the character-filled chuckling of the clarinets and the effortless way

the music segues into the Upper Austrian trios. You can almost see the

orchestra members, exemplary throughout, smiling at those points. In

the discussion disc Zander makes the inspired connection between the

solo fiddling in this movement and that in Stravinskyís "A Soldierís

Tale" which was, let us remember, just eighteen years away when

Mahler completed this symphony. Thereís a thought. I always find connections

like that send me back to the music with new ears and that, as always,

is the great value of the discussion disc which I suggest you listen

to after you have heard the symphony.

The great slow movement receives a luminous, seamless

performance from Zander and the orchestra with great line that just

fails for me to penetrate beneath the surface beauty. Here I see Zander

as a collector and connoisseur of Dresden china who has taken down a

much-loved piece from his shelf that he knows every inch of and wants

you to know every inch of too and come to love just as much as he does.

As fine a guide to the movement than you could ask for but, as with

the first movement, he is rather afraid of dropping his much loved ornament

and smashing it to bits. Zander the patrician once again. Donít get

me wrong, I like patricians, even in Mahler. There is a certain streak

of the patrician in Jascha Horenstein and I admire his Mahler conducting

above most. But I do wonder whether, over time, the extreme care Zander

takes over the first three movements will mean that this recording wonít

endure, wonít really endear itself to the listener in the way

others have and that is a serious matter in this most potentially endearing

of Mahlerís works. Again, only time will tell on that and it would be

nice to be proved wrong. Certainly in the great "collapse climaxes"

in the centre of the slow movement the music opens out wonderfully,

the great vistas as impressive as ever, and the gates of heaven burst

with a real surge of energy. It is then that the last movement enters

and is able to make the effect I so much admire. The tempo here is relaxed,

some might say too relaxed, but I enjoyed it on its own for the way

all the myriad details are allowed to emerge and, of course, as that

"beginning as ending" that is at the cornerstone of this work

and Zanderís realisation of it. For that aspect above all this version

earns its place in the discography.

Top recommendations remain Horenstein (Classics For

Pleasure 5748822), Kubelik (Decca Eloquence 4696372), Szell (Sony Classics

46535), Kletzki (Royal Classics DCL706722), Mengelberg (Grammofono2000

78844) and Abravanel (Everyman 08616471). The latter is well worth seeking

out for a more "chamber-like" feel to the work and another

remarkable soprano soloist in Netania Dervath.

A patrician and thought-provoking guide to Mahlerís

most approachable symphony casting the last movement in its correct

perspective.

Tony Duggan

See also

review by Terry Barfoot

![]() Camilla Tilling (Soprano)

Camilla Tilling (Soprano)

![]() TELARC 2CD-80555 [137.21]

TELARC 2CD-80555 [137.21]