Musical politics can be about as nasty as the other

sort. Willi Boskovsky was born in 1909, joined the violin section of

the Vienna Philharmonic in 1932, became a co-leader in 1939 and took

over the traditional New Yearís Day Concerts after the death of Clemens

Krauss in 1954. With his natural style and elegance (conducting from

the violin) he seemed the ideal person to take the New Yearís Day Concerts

out of the confines of Austria and into the world of Eurovision, and

by the late seventies it looked as if he would be conducting them for

all eternity. But he committed the unpardonable sin of falling ill before

the 1980 concert and was replaced by Lorin Maazel. In other walks of

life a person who falls ill and then gets better goes back to work afterwards,

but when there is a Vienna New Yearís Day Concert at stake the sin is

evidently too great. For the rest of his life (he died in 1991) he remained

active as a recording artist (it would be interesting to know how many

names the Vienna Johann Strauss Orchestra and the Vienna Philharmonic

had in common) and conducted his New Yearís Day Concerts where and when

he could. Unfêted, unheralded, he turned up in Milan to conduct

one New Yearís Eve during this last decade, while in Vienna Maazel continued

for a few years, until the traditional event became a catwalk for great

contemporary names, some of them singularly unsuited to the repertoire

(I donít refer to the two legendary concerts conducted by Carlos Kleiber).

I donít know who or why, but there was skulduggery here, mark my words.

Still, at least Boskovsky got to conduct the Vienna

Philharmonic. I donít know if Robert Stolz, whose Lanner CD I reviewed

a few months ago (BMG 74321 84145 2), ever conducted it in his long

life (1880-1975), but in Viennese eyes he was a conductor for the Symphoniker,

not the Philharmoniker. And, while Boskovsky recorded for Decca and

EMI, Stolz (even if the disc is now on BMG) recorded for smaller organisations.

Politics again?

Six items out of twelve are common to both discs, so

how do the two men compare?

Boskovsky was a violinist and the violins of the orchestra

always love it when one of their own turns to conducting so that the

bowing instructions issued from the rostrum make sense for once. Other

parts of the orchestra call them "top-liners". A Pavlov-dog

reaction on my part, maybe, but the cap does seem to fit here. All the

melodies are turned with elegance and style, while the accompaniments

are neatly dosed but always in the background. Itís pleasant, "schön"

in the best Viennese chocolate-box way, but a shade bland. Perhaps the

Vienna Philharmonic had a point in thinking it was time a conductor

with a bigger personality took over.

Stolz was a composer and he shows much more interest

and awareness in how the music is made. Let me give a few examples of

what this means in practice. When the waltz proper starts in Hofball-Tänze

you scarcely notice the counter-melody in the lower strings in Boskovskyís

performance. Stolz has the two melodies dialoguing with each other like

real counterpoint, and how much more characterful it sounds. Yes, he

is a little slower, but he uses this to bring out details Boskovsky

brushes over. His waltz rhythms are chunkier (this is particularly noticeable

also in Die Werber) but always alive, never heavyhanded. Listen, too,

to the introduction of Der Romantiker. The violins dig into their melody

with real passion and Stolz uses the chugging strings (kept well in

the background by Boskovsky) to give a sense almost of symphonic movement.

The wind chords in this introduction are not just played but Stolz seems

to be probing into them, bringing out chromatic lines or harmony changes.

What this all amounts to is that the music itself seems to have greater

stature under Stolz.

One curious feature is that in Die Romantiker and in

Pesther-Walzer Stolz includes a harp part, and enjoys its colouristic

effect to the full. There is no harp at all in the Boskovsky performances,

but I am not able to say whether it is an optional extra sanctioned

by Lanner himself. I am sure he would have appreciated it anyway.

I gave considerable praise to the Stolz disc. In retrospect,

perhaps I should have praised it more highly still. I donít want to

suggest that Boskovsky is actually bad, and I certainly enjoyed the

six pieces where I didnít have Stolz performances for comparison, but

since the non-specialist listener will presumably want only one of the

discs then the Stolz is the one to get, even if it is more fiercely

recorded. Honours are about even for the booklet notes.

Christopher Howell

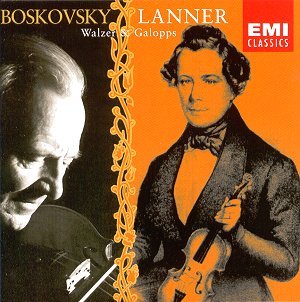

![]() Vienna Johann Strauss

Orchestra/Willi Boskovsky

Vienna Johann Strauss

Orchestra/Willi Boskovsky ![]() EMI CLASSICS

CDM 5 74372 2 [75í 51"]

EMI CLASSICS

CDM 5 74372 2 [75í 51"]