Lange-Müller was the child of a cultured and well-connected

Copenhagen couple. Hans Christian Andersen, Oehlenschlager (author of

the Aladdin play to which Nielsen wrote incidental music and

of the words sung by the choir in the finale of the Busoni Piano Concerto),

Niels Gade and Jenny Lind were amongst many famous house guests. Peter

became a prolific composer in this fecundly nurturing hothouse. Despite

his prolific production rate few of his works have any hold beyond Denmark.

The Symphony No. 1 runs for circa 35 minutes

and is in four movements. A briskly musing solo violin ushers in the

symphony in as individual a manner as you could want. This contemporary

of Stanford and Parry writes in a style that has the lift and flight

of Mendelssohn and Dvorak. The vivace is part Rossinian tarantella;

part Hardanger folk dance. The Brahmsian andante sets the scene

for an over-extended finale allegro con fuoco (not fueco

as claimed in the insert sheet).

The Second Symphony was only lightly revised

in 1916. It is substantially the same work as was first performed in

1889. The finale is specially memorable with an ever mobile allegro

festivo which rears up joyously, borne on the wings of Schumann's

Rhenish symphony. Otherwise Grieg haunts the andantes

and the sprightly third movement touches on material from provincial

dance halls - a Polacca. The composer's Dvorakian propensity

and light palate avoids high-flown emotions.

The orchestra is, as the very informative notes confess,

light on the string complement but the resulting balance is confirmed

by Mogens Wenzel Andreasen as authentic to the orchestras of Lange-Müller's

day. This avoidance of lush string tone certainly emphasises the chamber

'lighting' allowing us to appreciate orchestration that, although criticised

by contemporaries, is well put across by players, conductor and engineers.

While the performances do occasionally sound both caring and careful

there is much to enjoy here. However for all the references to late

romanticism these works are much closer to the 19th century pictorialism

of Ludolf Nielsen's orchestral suites, the Borresen symphonies 2 and

3, the Svendsen symphonies, Schumann 2 and 3 and the Mendelssohn Italian

and Scottish symphonies than to the exalted tense Tchaikovskian

romance of Borresen's First Symphony and Violin Concerto, the Macdowell

and Karlowicz tone poems, or of Arthur Farwell, or Vitezslav Novak or

even late Fibich.

Bostock notes parallels with Novak and Fibich. While

I struggle with the Novak links the Fibich references are clear enough

especially in the sparkling writing for wind instruments. Lange-Müller

however lacks Fibich's high tension drama - compare the Sejna Supraphon

mono recording of Fibich's Third Symphony.

I wonder if this present CD is the premiere commercial

recording of the symphonies. Possibly not - no such claim is made in

the booklet. In any event these works are not otherwise commonly available.

In the UK the complete ClassicO catalogue (with many choice items) is

available through DI Music.

There is much to enjoy here and as a listening experience

there are many original and ear-tickling moments. This music is, in

fact, quite a discovery and if you were as disappointed as I was by

the Grieg symphony do not be concerned; the Lange-Müller symphonies

are much fresher in impulse.

Rob Barnett

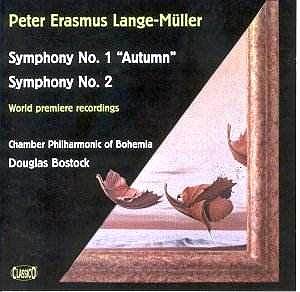

![]() Chamber Philharmonic

of Bohemia (Pardubice)/Douglas Bostock

Chamber Philharmonic

of Bohemia (Pardubice)/Douglas Bostock ![]() CLASSICO CLASSCD

370 [63.18]

CLASSICO CLASSCD

370 [63.18]