These are among Kreislerís last recordings. His May

1945 recording of the Concerto in C in the style of Vivaldi has already

been issued by Naxos (8.110922) and a few off-air broadcasts from 1943-45

have also appeared, mostly from the Bell Telephone Hour. None adds substantially

to his discography.

At 67 Kreislerís career was on the wane, exacerbated

by appalling injuries he sustained whilst crossing a New York street

in 1941 (a picture of the violinist, bloody and dazed, is reproduced

in Amy Biancolliís recent biography and makes for grim viewing). He

had recovered in time to record the first session on this CD, in arrangements

made by himself, in Philadelphia in January 1942. It would be idle to

suggest that Kreisler had emerged unscathed from the vicissitudes that

afflict any artist in his sixties; nor that his technical armoury was

entirely intact. The flatness of pitch in the higher registers of the

E string makes itself uncomfortably present on a few occasions (he seems

always to have played flat rather than sharp) and other blemishes, generally

minor, manifest themselves. The Kreisler tone of 1941, whilst still

beautiful, was not the ravishingly vibrant one of 1912.

We are, however, lucky to have these recordings at

all and can appreciate his miraculous rhythmic faculties Ė his rubato

is still an object lesson in phrasing. Listening to the extraordinary

flexibility of his 1942 Tambourin Chinois, a piece he had already recorded

five times in his career, is to wonder again at his musical daring and

inevitable rightness. His tempi are as deliberate as ever, his double-stopping

is admirably true, his portamenti are quick and subtle, his performances

affectionate and generous. In the somewhat boxy acoustic of the Academy

of Music a section of the Philadelphia Orchestra (contractually here

called the Victor Symphony Orchestra) plays a selection of his favourites.

The piquant arrangements are Kreislerís and feature drums, a glistening

harp, fey Celeste, woodwind shadowing the melody line, some surging

string tone and a confection of highly spiced Kreisleriana. In Caprice

viennois, a piece he had recorded six times, we can hear that rather

twee Celeste, as well as Kreislerís own supreme sovereignty of rubato.

That rhythmic licence and élan can fully be appreciated in the

Tambourin chinois where the middle section is superbly flexible. A little,

appropriate, tambourine crash adds to the excitement, as does Kreislerís

own word of pleasure at the end - "beautiful".

Elsewhere many distinguishing features of an elite

musicianís art can be savoured Ė the way he varies with infinite skill

the repeated phrases of Liebesfreud, the apposite decorations in Heubergerís

Midnight Bells, the way he allows the woodwind an imitative trill in

his arrangement of the Marche miniature viennoise, the beautiful bowing

in the Chanson Louis X111 and Pavane. Of course frailties co-exist with

his extraordinary musicality Ė the thinning tone, especially in the

Viennese Rhapsodic Fantasietta composed especially for the 1946 New

York sessions, the high position slips in the Heuberger, the flatness

of intonation.

Nevertheless these performances capture a great artist

in his final years and, if hardly representative of his best years,

they still allow us to savour those many qualities that had led him

to revolutionize violin playing and galvanize two generations of musicians.

The transfers are good and the notes, by Tully Potter, equally so.

Jonathan Woolf

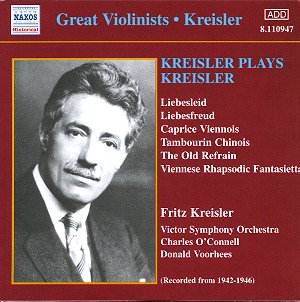

![]() Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962)

violin with

Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962)

violin with ![]() NAXOS HISTORICAL 8.110947

[60.06]

NAXOS HISTORICAL 8.110947

[60.06]