The heritage and activities of the Swiss composer Hans

Huber straddled the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. His music is

resoundingly nineteenth century and positively romantic. This comes

as no surprise as his teacher was Carl Reinecke at Leipzig.

This of course is what you would expect of the First

Symphony which was written in 1882. Its four movements bounce and

lilt their way through a mixture of the dramatic and the bucolic. As

a rule of thumb think in terms of early Mahler and the Schumann of the

Fourth Symphony and the Overture, Scherzo and Finale. Add in

festive elements from Dvorak and Smetana and an infusion from Brahms'

Third Symphony (the latter a work yet to be written at the time Huber

finished this symphony). In the last movement the sense of direction

is only fitfully sustained but this is surely down to the composer rather

than conductor, Weigle. I did not find anything specifically Tell-like

about the music except that the dramatic episodes might well reflect

Tell's nationalist struggle against the Austrian invaders.

The Seventh Symphony was written during days

of high tragedy and political uncertainty. As the Great War moved crushingly

forward the Russian Revolution opened up new and threatening possibilities.

Like many works of that era the music seems oblivious or deliberately

opposed to the spirit of the times. Rather like the Tellsinfonie

this work, subtitled The Swiss, claims a nationalist theme.

According to Dominick Sackmann's outstandingly useful notes the programmatic

inspiration of the four movements is concerned with the mountains. Certainly

the 14 minute first movement Auf den Bergen has some tempestuous

moments (e.g. 11.43) which are tougher than anything to be found in

the Tellsinfonie. There is also a swirling grandeur which again

might suggest the alpine peaks. The gruff and brusque close to the first

moment is quite masterly. The second movement, a Ländlischer

Hochzeitszug, is bright and spirited. The music is celebratory

with some whooping work for the horns - a touch of Mahler and Goldmark

here and even Ludolf Nielsen in his orchestral suites. This is not the

mountain music of say Delius or even Richard Strauss but it has about

it far more of the atmosphere of the high places than either Hakon Børresen's

Second Symphony or Rubinstein's Ocean has of the sea. The third movement

runs the risk of sinking into a turgidly dense mellow string and brass

texture but overall it works well. The sunset fade of the third movement

ties in, most aptly, with the movement's title Abendstimmung in den

bergen. The finale shows that Huber had absorbed the language of

Schumann and Mahler into his blood stream. Huber ends the symphony well

and freshly. No standard farewell gestures for him!

Both works are most affectionately pointed and spun

by Weigle and the Stuttgarters who must know more about Huber and his

style than any other orchestra. This is after all their fourth Huber

disc for Bo Hyttner's Sterling company. Let us salute not only the valiant

and insightful Mr Hyttner but also the boardroom and cheque book support

of the lottery fund of Kantons Solothurn, the Czeslaw Marek Foundation

(a tactful supporter of many projects) and the Friends of the Stuttgart

Philharmonic. Without them this disc would not have existed.

Only two more symphonies (4 and 8) to come now. After

that perhaps we will get to hear Huber's concertos for piano, violin

and cello.

Huber does not have the impressionistic freshness of

two young victims of the Great War: George Butterworth (in his Shropshire

Lad) or Rudi Stephan (in his Music for Orchestra). That said,

a real creative imagination is at work but within the palette boundaries

of Raff, Schumann, Brahms and earlyish Mahler.

Rob Barnett

THE HUBER SYMPHONIES:-

No. 1 William Tell (1882)

No. 2 Böcklin (1900)

No. 3 Heroische (1902)

No. 4

No. 5 Der Geiger von Gmünde (1906)

No. 6 (1911)

No. 7 Schweizerisch (1917)

No. 8 Frühlings-Symphonie (1920)

See also review

of other symphonies by Rob Barnett

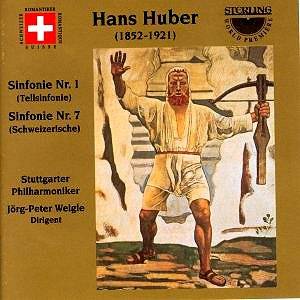

![]() Stuttgarter Philharmoniker/Jörg-Peter

Weigle

Stuttgarter Philharmoniker/Jörg-Peter

Weigle ![]() STERLING CDS-1042-2

[70.57]

STERLING CDS-1042-2

[70.57]