Haydn (senior) was appointed to the Esterházy

court in 1761. He arrived to find most of his non-string players, in

other words the winds and brass, had been recruited from the local army

bands, the so-called Feldharmonie. Though this arrangement was necessarily

unsatisfactory, a year later matters had considerably improved when

there was a change at Court as Nikolaus succeeded his late brother Anton.

Nikolaus proved to be far more sympathetic to the arts in general and

to music in particular. This attracted good players, especially when

they got wind (no pun intended) of the fact that salaries there were

better even than those on offer at the Imperial Court in Vienna. Among

these new recruits were horn players Thaddäus Steinmüller

and Johannes Knobloch for whom Haydn wrote these two horn concertos

(and others besides, either singly or for two horns and some of them

not extant). The first D major concerto (No.3) survives in manuscript

and is definitely by Haydn; the other one exists only in a copyistís

hand and there are apparently some doubts as to its authenticity. Though

not a touch on Mozartís four concertos for the same instrument, written

a quarter of a century later for Ignaz Leutgeb, they prove to be enjoyable

works and cover a wide range of possibilities as far as the horn is

concerned, for at this time it was still valveless and highly treacherous

to play. There was also the pioneering work being done at the time by

Anton Hampel introducing slide works to the instrument, which Haydn

also made use of. There is a wide variety of colour and tone in the

writing, much more use of the lower register than Mozart ever used,

for example, and the best music reserved for the expressive slow movements.

Haydnís younger brother, Michael, has always been a

rather more obscure figure, lurking in the shadow of either his older

brother or of Mozart. From 1763 and for 43 years, Michael spent his

career in the service of the Prince-Archbishops of Salzburg. The second

of them was Colloredo, who infamously had Mozart kicked out of his service

(whereupon Haydn succeeded him as organist adding it to his already

secure posts of Kapellmeister and Konzertmeister). Michael Haydn got

on well with the Mozart family and even collaborated with the 11 year-old

prodigy and a third composer (Adlgasser) on an oratorio, to which each

contributed a third of the music. Michael was a prolific composer, with

38 masses, secular vocal music, Singspiel operas (that is those with

spoken dialogue), 40 symphonies, concertos and chamber music to his

name. His Requiem, like Mozartís, was unfinished and was known by his

younger contemporary (resulting in some striking similarities when it

comes to Mozartís work). The Concertino included here probably comes

from his early Salzburg years, in the 1760s; in other words more or

less at the same time as his older brotherís essays in the same genre.

Unusually structured, the sequence of its three movements progresses

from a slow Larghetto, followed by an Allegro and finally a Minuet.

This probably implies that this is a fragment of an intended larger-scale

work. It had been his habit to write Serenades among which were movements

which highlighted one or more virtuosi in his 100 strong Salzburg orchestra.

These movements tended to be circulated separately thereafter, so the

three put together to form this Concertino may well have had a quite

different antecedence.

In this post-Dennis Brain era, horn players have to

be virtuosi of the highest calibre. Dale Clevenger (about whom nothing

can be deduced from the CD bookletís total lack of information about

him) generally produces the goods, apart from one or two high notes

on the cusp. He plays his own cadenzas to all three works, if not always

sufficiently sustaining their style. The Franz Liszt Chamber Orchestra,

with occasionally audible, but delightful, harpsichord continuo under

János Rolla gives sterling support.

Christopher Fifield

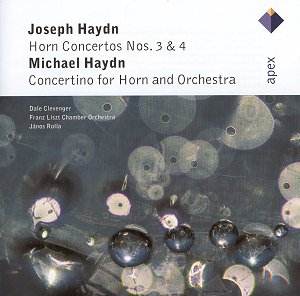

![]() Dale Clevenger, horn

Dale Clevenger, horn ![]() TELDEC APEX 0927 40825

2 [51.00]

TELDEC APEX 0927 40825

2 [51.00]