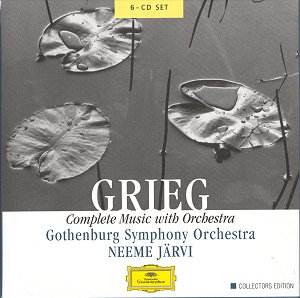

GRIEG Edvard (1843-1907)

Complete Music with Orchestra

Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra/Neeme Järvi. Other artists listed disc by disc

Recorded in the Konserthuset, Göteborg, dates as below

CD 1

Piano Concerto in A minor, op. 16 (1868) (1), In Autumn, op. 11 (1866 rev. 1887), Symphonic Dances, op. 64 (1898)

Lilya Zilberstein (pianoforte) (1)

Recorded 3.1993, 5 & 9.1988, 5.1986

[72.29]

CD 2

Suite - "From Holbergís Time", op. 40 (1884-5), Two Elegiac Melodies, op. 34 (1880), Two Melodies, op. 53 (1890), Two Nordic Melodies, op. 63 (1895), Two Lyric Pieces, op. 68, Lyric Suite, op. 54 (part orchestrated by A. Seidl)

Recorded 3.1992 (op. 40), 6.1992 (opp. 34, 63), 5.1992 (op. 53), 12.1991 (op. 68), 5.1986 (op. 54)

[77.20]

CD 3-4

Peer Gynt Ė Incidental Music, op. 23 (1875 with subsequent revisions)

Barbara Bonney, Maria Andersson, Monica Einarson, Charlotte Forsberg (sopranos), Marianne Eklöf (mezzo-soprano), Urban Malmberg, Carl Gustaf Holmgren (baritones), Wenche Foss, Toralv Maurstad, Tor Stokke (speakers), Gösta Ohlinís Vocal Ensemble, Pro Musica Chamber Choir, Knut Buen (Hardanger Fiddle), Paul Cortese (viola)

Recorded 6/1987

Sigurd Jorsalfar Ė Incidental Music, op. 22 (1872 rev. 1892 and 1903)

Kjell Magnus Sandve (tenor), Gösta Ohlinís Vocal Ensemble, Pro Musica Chamber Choir

Recorded 6/1987

Funeral March in Memory of Rikard Nordraak (1866), Norwegian Dances, op. 35 (1881) (orch. Hans Sitt)

Recorded 5 & 9/1988, 5/1986

[73.19 + 73.27]

CD 5

Symphony in C minor (1864), Landkjenning, op. 31 (1872 rev. 1881) (1), Olav Trygvason, 50 (1873) (2)

Randi Stene (mezzo-soprano) (2), Anne Gjevang (contralto) (2), Håkan Hagegárd (baritone) (1, 2), Gothenburg Symphony Chorus (1, 2)

Recorded 5 & 9/1988, 5 & 8/1992 (1, 2)

[75.53]

CD 6

Old Norwegian Melody with Variations, op. 51 (1890-1903), Songs with Orchestra (1894-5 from earlier voice/piano versions): The First Meeting (1), From Monte Pincio (3), A Swan (1), Spring (1), Henrik Wergeland (3), The Mountain Thrall, op. 32 (1878/9) (3), Before a Southern Convent, op. 20 (1871) (1, 2, 5), Bergliot, op. 42 (1871-1885) (4)

Barbara Bonney (soprano) (1), Randi Stene (mezzo-soprano) (2), Håkan Hagegárd (baritone) (3), Rut Tellefsen (narrator) (4), Gothenburg Symphony Chorus (5)

Recorded 5 & 9/1988, 5 & 6/1992, 5/1992, 8/1992, 12/1992

[73.33]

DG 471 300 2

Crotchet £34.99 AmazonUK AmazonUS Amazon recommendations

This is a gathering together of recordings made over a period of about seven years and covers everything Grieg wrote involving an orchestra in some way. I toyed with the idea of rearranging it to listen chronologically, and so get an idea of Griegís development, but few listeners are likely to want to do this and I feel the compilers of sets like this should also be judged on their success or not in making each disc a listener-friendly experience, so I opted for a disc-by-disc account.

CD 1

The ultra-popular works are not really the point in this kind of set so I wonít dwell on the Piano Concerto but it is in fact a very fresh and attractive performance. The performers allow themselves plenty of elbow room for rubatos and rallentandos but the tempi themselves are kept steadier than usual and certain time-honoured exaggerations are avoided. The orchestra enters in tempo after the first movement cadenza and due consideration has been given to the fact that if Grieg wrote the adagio in 3/8 rather than 3/4 he couldnít have wanted it all that slow. The dances in the finale have exemplary bounce at steady tempi. I wonít be throwing out Lipatti, Solomon or Curzon, but Iím glad to have this.

In Autumn is the earliest orchestral work which Grieg acknowledged (for the suppressed Symphony see CD 5) though we hear it in a later revision he made. The gentle moments have a wistful poetry which is most touching but the livelier folksy themes are a bit too obvious. Though cast in sonata-form the overall impression is of a rather stop-go construction, and this does nothing to disguise its length. It is worth hearing occasionally for its fresh charm.

By Symphonic Dances Grieg meant that the four pieces correspond to the four movements of a symphony. The conductor who programmed this work in place of a real symphony would leave his public very undernourished, alas. The second is a charming piece but the others get up no sort of momentum and often try to hide the fact by making a lot of noise. Real folk themes are employed and invite the reflection that perhaps the reason for the success of Dvorakís Slavonic Dances (a set of which can be listened to as a satisfying alternative to a symphony) is that the composer writes his own themes. It is surprising how often the composer who bases a piece on folk tunes ends up by proving Constant Lambertís dictum that "all you can do with a folk-tune is play it again louder". The major exceptions to this rule are the Stanford Irish Rhapsodies which sometimes sound more symphonic than the same composerís symphonies (but see my comments on op. 63 in CD 2 below).

Excellent performances.

CD 2

A flowing, gracious, and also deeply felt, performance of the "Holberg" Suite confirms this as one of the most perfect of romantic suites inspired by the baroque. The following two pairs of melodies are all arrangements Grieg made from his songs and show him at his most romantically melodious. Järvi plays them passionately but without indulging them; he has the gift of letting them unfold naturally. Hear him caress "The First Meeting" without ever lapsing into sentimentality Ė this is a highly attractive piece in his hands.

The most remarkable music on this disc is the Two Nordic Melodies, and, having been sniffy about Griegís use of actual folk melodies in the Symphonic Dances I can only say I am astounded at what he does here (the more so when the two works have consecutive opus numbers!). The first is profoundly inventive in its textures and builds up with great breadth to an epic statement that looks forward to Sibelius. The second is delightfully fresh and again uses the string orchestra most imaginatively.

After so much string music, the entry of the oboe in "Evening in the Mountains", the first of the Two Lyric Pieces, is unforgettable. This is an example of how imaginative programming can add to the impact of an already beautiful piece. Järvi draws the maximum atmosphere from this desolate Tristan-inspired poem, and then keeps the following "Cradle Song" very much on the move, always gently rocking.

Of the Lyric Suite, only the first, "The Shepherd Boy", was orchestrated by Grieg, for strings only. He adds a striking dimension to a piece whose piano original has never fired me with much enthusiasm. The remainder were orchestrated (for full orchestra) by Anton Seidl and shown to Grieg, who protested that they were too heavily Wagnerian. He rejected one, "Bell-Ringing" (though it is played here) and pruned the orchestration of the others before permitting publication. I can only say he didnít prune it anything like enough. "Norwegian March" and "March of the Trolls" are reasonable enough in a riotous sort of way but it is a pity to hear the "Nocturne" hammed up in this pre-Hollywood style. Järvi adopts a tempo that would certainly be too slow for the piano original but which is fair enough for this version given the premise that the thing had to be played at all. In any case, if you hanker after the gentle purity of Griegís original conception you will want to hear it played on the piano.

CD 3-4

A few conductors made LP selections from Peer Gynt which went beyond the traditional two suites, most famously Beecham and Barbirolli, and not forgetting Sir Alexander Gibsonís World Record Club selection. But it was a Unicorn set made in 1978 under Per Dreier (transferred to CD in 1987) which brought the revelation that Griegís music, long derided for having prettified Ibsenís stark and unsentimental drama, had measured up to the project far better than was generally believed. Not that the music outside the extended selections usually amounts to more than fragments and melodramas, but so chillingly atmospheric and dramatically potent are they that even the familiar pieces appear under an entirely new light. In any case, a "Morning Mood" as scrupulously phrased and paced as Järviís is far from being the anaemic piece if tone-painting we know from popular orchestral concerts of yore. Beecham also had a choir in "In the Hall of the Mountain King" but it was not very evident. Here, with the sinister aspects of the orchestration relished and the choir brought right forward the effect is spine-chilling. For what it tells about Griegís potentialities as a composer this complete Peer can only be compared to the revelation Ė also dating from the 1970s Ė of the ur-Mussorgsky in all his barbaric power.

A very detailed note from Finn Benestad and Rune J. Andersen, editors of the music as published in Vol. 18 of the Complete Grieg Edition, state that this performance, based on that edition, is the first recording of the definitive score. I donít have the Dreier set to hand but I have tracked down a review of both this and the original issue of the Järvi and it would seem that the principal differences are that Dreier adds Ė on the grounds that they were included at a revival in Copenhagen in 1886 - the "Norwegian Bridal Procession" (an arrangement by Halvorsen of a piano piece) and the first three of the Norwegian Dances, op. 35 (which you get on their own account at the end of CD 4, but see my comment below), but did not include any of the melodramas. As stated above, these add strongly to the total effect, to the extent of making preference for Järvi automatic. In any case Dreierís conducting was generally felt to be sound but underwhelming, something that could most emphatically not be said of Järvi who, as suggested above, packs a real punch when necessary but is also highly sensitive in the gentler pieces. The vocal contributions add a definite dimension to the whole (but the original issue printed texts and translations), with a welcome presence from Barbara Bonney as Solveig. If you want just the two suites, the booklet lists the tracks you need to programme in order to do that.

Sigurd Jorsalfar is also claimed to be the first recording of the authentic version and in this case, too, it was preceded by a "complete" Unicorn version under Per Dreier which I havenít heard, so I canít say what the differences are. Sigurd is a tale of romantic chivalry and draws from Grieg music of a certain heroic dignity, mostly diatonic and brassy. There is no revelation here comparable to that of Peer Gynt. There are no melodramas or fragments, apart from the opening horn calls which are simply arpeggios that anybody could write. In addition to the usual three orchestral pieces (also here you get instructions for programming just these) there are two rousing ballad-style numbers for tenor and chorus. These are well worth hearing, and the Act 1 Prelude, based on the same theme as the final chorus, gives a certain symmetry to the sequence. But the first Interlude is mostly, and the second wholly, based on the Homage March, in itself not exactly unrepetitive. This may have a point in the theatre but when the pieces follow each other consecutively it seems pious completism to hear it three times over.

The tenor has an attractive if sometimes tremulous timbre and the male voices are rough on their top A (it only happens once) but the orchestra is splendid and Järvi sees that the spirit is always right.

The Funeral March for Rikard Nordraak is not thematically memorable but it is a striking expression not only of numbed grief but also of protest at the death at a mere 23 years of a friend in whom Grieg had such high hopes. Emphatically more than a pièce díoccasion.

The Norwegian Dances were written for piano duet and orchestrated by Hans Sitt. Since these orchestrations were made after Griegís death (the German booklet note tells us this, the English one does not) they do not have the semi-authority of Seidlís arrangements in the Lyric Suite, which Grieg saw and revised. That being so, arguably they have no place here. The puzzling thing is that (as I have pointed out above) the first three dances were included in a Copenhagen revival of Peer Gynt in 1886, and so orchestrations must have been made or at least approved by Grieg for that occasion. Do they still exist?

However, Sitt did a very expert job. These pieces are less pretentious than the Symphonic Dances, but I feel their place is in the domestic hearth envisaged by their original version. Though the music is very charming it lacks development, something which is emphasised by hearing it on a full scale orchestra. One feels, as one does not with the Dvorak Slavonic Dances or even the Brahms Hungarian Dances, most of which were not orchestrated by Brahms himself, that a sledge-hammer is being used to crack a nut. Lively performances from Järvi but perhaps for once he tries to read too much into the slower sections at times.

CD 5

In 1863 Grieg went to Copenhagen to study with Niels Gade, then the leading Scandinavian composer. For some reason Gade found it rather reprehensible that Grieg had not written a symphony yet and urged him to do so. The result, completed the following year, received a few performances and was then withdrawn by Grieg, perhaps because by then Svendsenís first symphony, with its much more natural feeling for symphonic form, had appeared (I recently had the two Svendsen symphonies to review on Chandos CHAN 9932) and Grieg hoped that Svendsen would develop the art of the symphony in Norway, leaving him free to explore the more poetical forms congenial to him. He arranged the two middle movements for piano duet a few years later but he labelled the manuscript of the symphony "must never be performed", a wish that was respected until 1981. The reputation of a composer with the public has a way of standing or falling by his symphony if he happened to write one, so it as well that for long years this work remained hidden from view; heaven forbid that Griegís reputation should have depended on a piece so uncharacteristic both in its themes and with regard to what his lifeís work was aimed at doing.

That said, the first movement is not unattractive. If it doesnít sound like Grieg, it sounds at least as Nordic as Gade ever did and the contemporary listener who heard both this and the Svendsen might have found hints that this was the composer of the two who would later move and inspire his public. It was written and orchestrated in 14 days and perhaps this accounts for the sense of youthful enthusiasm which, more than any symphonic skill, holds it together. Unfortunately the two middle movements are very watery and characterless indeed. The finale may be a conscious effort to avoid Gadeís habit of spoiling an otherwise good symphony by lapsing into four-square jubilation, but this stop-go construction is no solution to the problem. Järvi does what he can.

At under seven minutes, Land-sighting is nonetheless a work of real stature, its broad hymn-like themes growing in intensity to reach an inspiring conclusion. As it is short it perhaps does not belie Griegís reputation as a miniaturist, but in another sense it is a revelation since it is an epic statement in miniature. Anyone who enjoys Elgar in patriotic vein will thrill to this Norwegian equivalent.

Sigurd Jorsalfar and Landsighting were collaborations with Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, with Ibsen the leading Norwegian poet of the day. Bjørnson was thrilled by the results and proposed the creation of a large-scale dramatic work which would be the Norwegian national opera. Unfortunately, after three scenes Bjørnson left Norway for Austria and Italy and did not return for many years. Grieg, feeling he had been left in the lurch, became estranged from him and fifteen years passed before a rapprochement came about and Grieg conducted the three completed scenes of Olav Trygvason. The music was enthusiastically received but nothing further was written.

Could Grieg have measured up to a large-scale heroic national opera? The evidence of these 35 minutes is that he probably could. It would have been a tableau opera, rather like Boris Godunov, but that need be no bad thing and he lacks neither breadth nor heroic tone. The third scene, with its choral dances, is quite thrilling. Apart from an unlovely contralto the performance is superb, but we needed the words, which were present when the CD was first issued separately.

CD 6

The Old Norwegian Melody takes a brief but attractive theme and the ensuing variations alternate poetry, delicacy and strength. Some of the variations are very brief indeed but all make their point (Järviís characterisation of them is always spot on) and there is a more extended Adagio molto espressivo before the last group which constitute a majestic finale which then dies away so that the work ends with a very poetic coda.

Has this quiet ending discouraged conductors (with the notable exception of Beecham) from taking the piece up? If so, shame on them, for this is clearly the masterpiece among Griegís works for full orchestra and deserves a place in the repertoire alongside the variations of Brahms, Dvorak and Elgar.

The listener will find it interesting to compare the first song here, The First Meeting, with Griegís arrangement of it as the second of the Two Melodies, op. 53. On his own Järvi digs into it and draws it out (it lasts a minute longer) with very rich string tone. The music can take it but a light soprano voice probably couldnít, and Barbara Bonney gives a performance which is just as moving in its tender restraint as is the other in its more overt passion. Järvi adapts himself to Bonneyís quite different conception with admirable musicianship.

These orchestral songs (arranged by Grieg from piano originals) are all highly attractive. The absence of the words is once again regrettable though such melodic writing can be enjoyed for its own sake, especially when so well sung. Spring is an outstandingly beautiful piece.

Being originally conceived for just voice and piano, these songs are mainly intimate in expression. The Mountain Thrall was intended for an orchestra of strings and two horns from the start and is a fine example of the composerís epic vein. Grieg himself was particularly fond of it and felt that with it he had "accomplished one of the few good deeds of my life".

Whoever made the decision not to print the words in this set, which were included with the original issues, most emphatically has not done one of the few good deeds of his life. I keep returning to this, and I have to since "Before a Southern Convent", while it has its moments of lyrical writing, has many more where we clearly need to know what is being said. But above all, it is quite ridiculous to expect any but a native Norwegian to sit through over 17 minutes of recitation Ė Bergliot - without knowing what it is about. This is especially so considering that actual sustained music is rare; for the most part Grieg illustrates the poem with tremolandos and dramatic chords. I daresay it is very effective, and Norwegian would seem the ideal language for near-hysterical dramatic declamation, rather like Münchís "The Scream" come to life. But only a Norwegian is likely to hear it a second time. The booklet notes are informative but, if space really forbade a few pages more, in the case of the vocal works perhaps it would have been better to keep the words and omit the note. Or could not the note on the piano concerto have been omitted, since it is sufficiently well-known not to need it?

I must confess that Grieg was one of my teenage passions, and like most such it didnít seem to last. Well-disposed as I am towards romantic music generally I never systematically explored him beyond the well-known pieces. There must be many music-lovers who would say the same and I recommend this box to all of them. There are some disappointments (particularly the Symphonic Dances) but in general this is a small output of consistently high quality, and a wider range than one might expect. Performance and recording are of such quality as to ensure that it is not necessary to seek alternative versions of these works save perhaps the Piano Concerto and those few that were recorded by Beecham. The notes are good, in three languages, so all that is lacking for a definitive presentation is the texts. Why will companies spoil the ship for a haíporth of tar? And if they say there wasnít room in the booklet, I reply that they havenít worried unduly about questions of space, for the box itself is high, wide and handsome, with the result that it wonít fit into any of the shelves or drawers where I keep my CDs. Now I call that real smart.

Christopher Howell