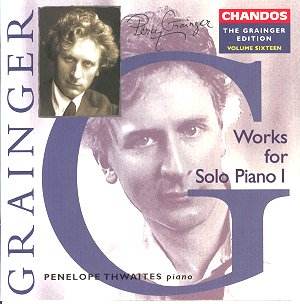

Penelope Thwaites’ résumé in the accompanying

booklet leaves the reader in no doubt of her devotion to the Grainger

cause. She was Artistic Director of London's first international Grainger

Event at St Johns, Smith Square in 1998 and presented Grainger as BBC

Radio Three's Composer of the Week in 1996. In 1991, she received the

Percy Grainger Society's Medallion for services to the composer's music.

Her booklet notes to her own recital are exemplary.

There are several premiere recordings here: the two

preludes, the Gigue (from Birthday Gift) and Seven men from

all the world. In this repertoire, there are various other pianists

one should consider. Of these, the most direct comparison is Martin

Jones on Nimbus (NI1767, a five disc set). Neither pianist takes the

breath consistently away, either as a virtuoso or in their ability to

make the piano sing, although Jones shows a consistent musicianship

which is always pleasing.

Thwaites has decided to work through Grainger’s output

based on the date of genesis of a work’s idea (even if this did not

turn up on piano until much later). So, all of the pieces on this disc

date, originally at least, from the decade 1893-1903. The juvenilia

of the Bach-inspired Preludes and of the Klavierstücke,

whilst interesting and pleasant to hear will never, I think, go through

my speakers again. If the E major Klavierstück is merely

pretty, at least it avoids the meandering of the A minor. Perhaps if

I had to choose a return visit to any of the works on this disc, it

would be to the Eastern Intermezzo (originally 1898/9, set for

piano in 1922). Grainger would hear the Chinese community of his childhood

perform in Melbourne, and this probably led to this clearly affectionate

tribute.

Thwaites’ strengths are nostalgia and simplicity. So,

the Walking Tune is plainly but effectively presented, and the

Three Scotch Folksongs are imbued with integrity as well as warmth.

For Near Woodstock Town (1903 for chorus, arranged for piano

in 1951), Grainger employed more progressive harmonies: Thwaites, to

her credit, maintains the nostalgic element here.

Perhaps she could have played the showier pieces with

more abandon and let her hair down more in the Flower Waltz Paraphrase

(although she clearly enjoys the more florid passages). The final In

Dahomey (subtitled ‘Cakewalk Smasher’), suffers a similar fate.

It is always disappointing when the booklet notes are

more interesting than the music they refer to. The musicological interest

of this issue is great, and libraries should avail themselves of a copy

as a matter of course. The purely musical interest, may I suggest, is

somewhat less.

Colin Clarke

Penelope Thwaites

(piano).

Penelope Thwaites

(piano).