These operas are bound up in history but not bound

by history. Thus this Italian excursion into the English Tudors uses

history as a vehicle for music and adapts it to provide a better plot.

The best example of which is that Elizabeth I never met Mary Stuart

at Fotheringay but she does in Donizetti's operatic imagination .. and

to great dramatic effect.

The operas are usually those involving Elizabeth I

whereas here Anna Bolena replaces the conventional first in the series,

Elisabetta al Castello di Kenilworth. She, of course, was Elizabeth

I’s mother (a fact not mentioned or relevant to the opera). But Anne

Boleyn was a Queen in her own right: so the box title stands anyway.

It is a happy operatic substitution. After ten years

of modestly successful operatic productions Anna Bolena was Donizetti’s

first great success. He was now on his way to become a bel canto

exponent of original music with some important musical development

in his attempts to blur the aria / recitative structural division.

Enough of general history. Let us turn to the operas

themselves. Anna Bolena, was his 31st opera and was

written during a month’s visit to Giuditta Pasta’s house. There is a

strong suspicion of a significant input by Pasta for her role in the

premiere. Felice Romani provided a taut concise libretto. Donizetti

responded with mellifluous economic music, which he aimed "to serve

the situation and give the artists scope to shine."

That gift horse is not ignored. To support them we

have a Symphony Orchestra (not an opera house orchestra) in fine form.

With sound in depth they make a powerful contribution, never threaten

to overwhelm and deliver some emotive delicate solo instrumental introductions.

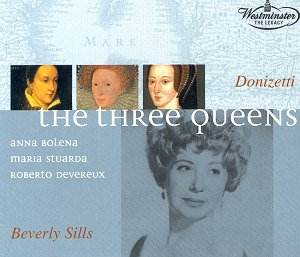

These artists have strong voices. Beverly Sills leads

the way with excellent diction. Very occasionally forte threatens tonal

quality; but her delivery of the two final arias displays a range of

hit and held notes and runs with tonal variation second to none. She

even manages to foreshadow the descent into partial delirium with notes

of piercing intensity at earlier stress points of the role, for example,

during S’ei t’abbore, io t’amo ancora.

The aria-less Henry VIII of Paul Plishka combines

superbly with the gentler moments of Sills and the powerhouse of Shirley

Verrett’s Seymour. Another note hitting soprano who can produce some

splendid tones. I thought Stuart Burrows was excellently cast as Percy.

A brilliantly clear and tonally varied voice. Patricia Kern’s Smeton

was the hesitant page with real vocal acting.

Happily the soloists combine to provide some outstanding

moments. The quintet towards the end of Act I is urgently compelling.

Before moving on, a brief word of comparison cannot

be avoided. Sutherland’s Anna Bolena from Decca (421 096) is

pure Sutherland. An unmistakable voice. Superlatives abound. But if

you are not one of her ardent fans here is a real alternative with a

cast and orchestra to rival Decca.

We move on from Elizabeth’s mother to her regal rival

in Maria Stuarda, Donizetti’s 46th opera. With text

by the little known lawyer Giuseppe Bardari, serious problems with censors

(not surprising really: the execution of a Catholic Queen would not

be popular with authorities in a catholic country) and a good physical

scrap between the two lead sopranos in rehearsal, adds a background

frisson. Banned, revived, refined in text and music, but it survived

– thank goodness. And here is a performance to echo that.

Again we have a Symphony Orchestra. The overture is

in stately fulsome sound. After one or two curious phrasings in the

overture the pace and tempi are instantly tightened for the rest of

the production.

We have three soloists from our previous opera: Sills,

Burrows and Kern. And if you thought Sills and Burrows were good in

the last performance then listen to them here.

The title role is sung by Sills. Eileen Farrell sings

the role of Elizabeth. She starts with some quite excellent vocal contrasts

over the whole of her vocal range, followed swiftly by some restrained

but fine coloratura. In the first Act she combines superbly with Burrows

(Leicester) and Louis Quilico (Talbot). Burrows provides some superb

sounds at many points but particularly Quest’ immago with emotional

falling notes sung piano: and later when he reluctantly describes

the beauty of Mary to Elizabeth. He contrasts with the darker voiced

Quilico in their totally enjoyable Act I duet.

Sills does not appear until Act II but when she does

her first aria is delivered with startling clarity and much colour.

Indeed in this performance there seems to be a more refined Sills on

stage. There are higher notes delivered piano at which she is

so good and with excellent vocal acting.

Christian du Plessis is the unforgiving and trenchant

Cecil persuading Elizabeth of the wisdom of the death of Mary. It is

not the biggest role but it is sung with consummate skill. Kern’s role

as Mary’s nurse (maid) is small indeed but, as with the chorus, it is

important that they contribute to the whole, which they do well

The helpful and interesting accompanying booklets give

full libretto and English translation, synopsis and history. Each has

"An Appreciation and History" of Westminster together with

some background notes on the only soloist to appear in all three recordings:

Beverly Sills. For this opera in addition we have a translator’s note

about Bardari’s use of names and the translation liberties taken: thoroughly

helpful and to be applauded.

Onto the final opera and Donizetti’s 57th,

Roberto Devereux. This was written at a low point in his life,

after the death of his parents, the arrival of a stillborn child and

then the death of his wife. The booklet reminds us that his librettist

Cammarano helped himself to work by Felice Romani. All that no doubt

explains the hugely emotional content.

We have a change of Choir: from the John Alldis Choir

of the previous two to the Ambrosian Opera Chorus. More importantly,

here we have the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra under the baton of Charles

Mackerras. Without me saying more you can almost guarantee that here

will be a full resonant sound delivered with sharp precision and timing

and not missing any orchestral nuance.

I wish I could say the same for the soloists. I can

for Sills but for much of the time (not all) they seem to think that

they are trying to fill an opera piazza with sound rather than a microphone.

Forte rules and it is not OK. Thus, for example, when Nottingham,

sung by the beautifully toned Peter Glossop, reaches Scellerato!…he

has no more left for his blind rage. It is not until the last Act that

they permit themselves some serious tonal contrast and expression.

This is particularly true of Beverly Wolff’s Sara who

in the last Act uses her powerful voice to great tonal effect. Robert

Ilosfalvy sings the title role. He comes to tonal variation and piano

early in his duet with Sara. Although he does not maintain that his

final Act assurance of Sara’s chastity is delivered with dignified anguish.

It is Sills who shows vocal versatility throughout. Although she does

not ignore power she recognises that piano can be a formidable

tool of contrast.

This set is a serious addition to any opera lover’s

collection. The reproduction on CD is quite excellent and whilst you

can occasionally detect hiss that is an irrelevance in the overall context.

Robert McKechnie.

![]() London Symphony Orchestra

/ Julius Rudel

London Symphony Orchestra

/ Julius Rudel ![]() London Philharmonic Orchestra

/ Aldo Ceccato

London Philharmonic Orchestra

/ Aldo Ceccato ![]() Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

/ Charles Mackerras

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

/ Charles Mackerras ![]() WESTMINSTER - THE LEGACY

471 227-2

WESTMINSTER - THE LEGACY

471 227-2