Cherubiniís opera was first performed on 13 March 1797,

one of the few stage works written during the French revolution and

still performed, albeit rarely, today. After only twenty performances

it was not performed in France until the mid-20th century,

but it seemed to strike a more popular response in Germany, where the

dialogue was replaced by recitatives composed by Franz Lachner in 1855

and this became the standard form until the 1980s (in other words even

after the date this recording was made). Most of the composers who were

said to admire the opera were Germans, Beethoven, Weber, Schumann, Wagner,

and Brahms (the last-named commenting that this opera Ďis a work we

musicians recognise amongst ourselves as the highest peak of dramatic

musicí). England heard it in 1865 for the first time (Therese Tietjens

in the title role) at Her Majestyís Theatre in London, with recitatives

supplied by Luigi Arditi, and at Covent Garden five years later. Italy

had to wait until 1909 before it was staged at La Scala in Carlo Zangariniís

translation (the combination of Lachner recitatives and Zangarini translation

featured here). Again indifference seems to have been the order of the

day as it was not done again until 1953 when Callas sang it at the Maggio

Musicale Fiorentino. Buxton and Covent Garden have reverted back to

both French and dialogue versions during the 1980s.

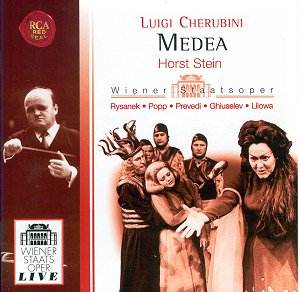

Mention of Tietjens and later Callas firmly place this

opera among those with a pivotal dramatic soprano part of fiendish virtuosity,

later developed by the likes of Bellini et al, and sure enough the star

of this show has to be, and is the late Austrian soprano Leonie Rysanek

(1926-1998). She was one of the most exciting singing actresses, initially

in Wagner and Strauss roles, latterly also in Janacekís operas, and

this recording was made, when she was in her forties, just at the time

her middle range was developing, ĎI have two things by nature,í she

once modestly remarked, Ďan extremely good top and extremely easy pianissimoÖand

fortissimo up there, from the G upí. She was not best judged by recordings,

you needed to see her elemental, raw-nerved acting to complete the picture,

and she often needed to warm up before getting into top gear. She is

best remembered for her portrayals of Sieglinde, Kundry, the Empress

(Frau ohne Schatten), Senta, Elisabeth, Chrysothemis and Lady

Macbeth, but there were a host of others as well as those she preferred

to leave to her great contemporary and rival Birgit Nilsson (Turandot,

Isolde, Elektra and Brünnhilde). The mouth-watering cast list also

has a luxuriant Lucia Popp singing the role of Dircé (described

on this CD as its German equivalent Glauce), making sure she gets the

audienceís plaudits in her Act one aria before Rysanek appears. This

Czech-born but Austrian-based soprano who died too young of a brain

tumour (1939-1993) is in golden voice, for this was the time her voice

was developing from the dramatic coloratura Queen of the Night through

the heavier lyrical Pamina, gathering a bloom to the sound, before entering

the repertoire territory of the more powerful spinto voice. She was

one of operaís most intelligent interpreters, gifted with a voice of

extraordinary natural beauty. But notwithstanding Popp, the excellent

singing of Margarita Lilowa as Medeaís accolyte and, in her Vienna debut

year, the emerging 26 year-old coloratura soprano Edita Gruberova in

the small cameo role of First Maid right at the start of the opera,

from the chilling moment of Rysanekís first entry as the vengeful Medea

everyone else is overshadowed as she pleads, implores, simpers before

she finally murders her rival and goes on to wreak carnage on her children

to revenge herself on her faithless husband.

Of the men, both Prevediís ringing tones (albeit occasionally

flat it must be said) in the role of Medeaís husband Jason and Ghiuselevís

imposing bass as Creon give stylish performances, with Prevediís Verdian

quality underlining the 19th century Italian style of the

recitatives. Lachnerís pastiche replacement of the original dialogue

does not go back far enough to 1797 - the year of Schubertís death and

with Beethoven about to come into his own - for each time we hear another

pure Cherubini set aria or ensemble the time machine changes gear. Horst

Stein, conducting the house orchestra and chorus (in 1972 he was a principal

conductor at the Vienna Opera and about to take over the Hamburg Opera

as General Music Director) paces it all dramatically, phrasing the music

with both elegance and care, and there is fine playing from the VPO.

It must have been quite a night thirty years ago, and itís a pleasure

to be able to relive it in this series of releases of momentous occasions

over the past half century taken from the archives at the Opera House

on the Ringstrasse. The transfer is highly satisfactory with audience

applause, though not the mixed reception of cheers and boos apparently

given to the productionís design team at the final curtain call, but

to compensate thereís the occasionally audible contribution from the

prompter, or rather souffleuse, all adding to the atmosphere

of a memorable recording. This is not Cherubiniís Medea, it is

the glorious Rysanekís.

Christopher Fifield

![]() Libretto by François

Benoit Hoffmann

Libretto by François

Benoit Hoffmann ![]() RCA RED SEAL 74321 79595

2 2CDs [117.46]

RCA RED SEAL 74321 79595

2 2CDs [117.46]