|

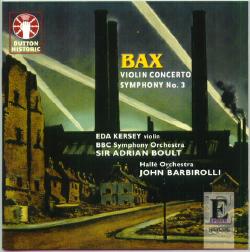

BAX: Violin Concerto. Eda

Kersey (violin), BBC Symphony Orchestra, Sir Adrian Boult (rec.23

February 1944). Symphony No.3. Hallé Orchestra, John Barbirolli

(rec.31 January 1943 and 12 January 1944). Dutton Laboratories CD:

CDLX 7111.

THE SIR ARNOLD BAX WEB SITE

Last Modified August 1,

2001

Dutton Laboratories CD: CDLX

7111

Review by Rob Barnett

In one fell swoop Dutton

restores the classic Barbirolli version of Bax 3 to the catalogue

and ushers in the first commercial release of Eda Kersey's traversal

of the Violin Concerto. Both are leading documents of their time and

have much to tell us about Bax and performance practice.

The Concerto was written for

Heifetz but disdained by him because, as Lewis Foreman tells us in

his habitually exemplary liner notes, the work was insufficiently

challenging. Truth to tell it is an enigmatic work if your reference

points are the symphonies. It makes more sense if you group it with

things like Maytime in Sussex and the overture Work in Progress.

Even then it does not quite fit because this is a work with some

fire in its veins. The composer likened its style to Raff but for me

it is a dashing and poetic blend of Russian romance (vintage

Tchaikovsky and Rimsky in Sheherazade mode - try 09.03 in the first

movement) and Straussian panache of a type Bax also used in the

Overture to a Picaresque Comedy.

There is only one other

recording - a perfectly good and enjoyable version on Chandos. Lydia

Mordkovich (the Chandos soloist and a most welcome and imaginative

regular on that label) does not imbue the work with quite the

ferocity that Eda Kersey finds. The last time I heard anything

approaching this was Dennis Simons version, impetuous and poetic,

broadcast by BBC Radio 3 circa 1979 in which the BBC Northern

Symphony were conducted by that very fine Baxian, Raymond Leppard

(still Indianapolis-based?). Now that is one broadcast that cries

out for commercial release. Ferocity in Bax can be glimpsed in many

of the older school conductors' efforts as in the case of Stanford

Robinson's Bax 5 and Eugene Goossens' Bax 2 - both BBC tapes from

the 1950s and early 1960s. Goossens' devastatingly gripping Tintagel

with the New SO on 1930s 78s is also an object lesson in what Bax

scores can gain from keeping things moving forward.

Kersey was to die in 1944 at

the age of only 40. How sad a loss! It would have been wonderful if

her version of the Arthur Benjamin Romantic Fantasy premiere had

been similarly recorded by the BBC. The Fantasy was dedicated to Bax

and the two corresponded regularly.

The recording of the concerto

is in muscular mono prone to only one blemish: when the orchestra

rises above ff on emphatic music the treble stratum succumbs to a

shredded or shattery quality likely to be noticeable only if

listening on headphones. Otherwise the audio image is stable and

without fault though unsubtle by comparison with the Symphony's

commercial recording.

The Barbirolli Bax 3 is likely

to be an old friend to many Baxians. First issued in 1944 under the

auspices of the British Council, it was finally issued on LP by EMI

in the 1980s. In the 1990s it reappeared (though with a very short

lease) in 1992 on EMI CDH 7 63910 2 (ADD) on the Great Recordings of

the Century series. When the original 78s had been deleted their

place had been filled (after a fashion and after years of silence)

by Edward Downes' LSO recording on an RCA LP -- later reissued on

the Gold Label series in circa 1977 (the year of the Silver Jubilee

in the UK).

For this Baxian, the Third

Symphony counts as one of the most static of the seven - a natural

partner to the Seventh. Its rhapsodic Russophile sympathies are much

in evidence with hints throughout of Rimsky's Antar and Russian

Easter Festival and of Stravinsky's Firebird. I would tend to

bracket it with his own Spring Fire, Bantock's Pagan Symphony and

Vaughan Williams' Pastoral rather than with the dynamic turbulent

front-runners of the 1930s such as the Moeran, Walton 1, VW4 and

Bax's own 5 and 6.

Barbirolli invests the

Symphony with great feeling - molto passione. Every detail is

attended to with great and amorous care. Has the anvil blow at the

crown of the first movement resounded as satisfyingly in any other

recording - I think not?

The dedicatee of the Symphony

(Sir Henry Wood) can be heard in a tantalising fragment of a Queen's

Hall rehearsal of the Third on a Symposium CD. His illness since the

late 1930s (he was to die during the Summer of 1944) robbed us of a

Wood-conducted Bax 3. It would not at all surprise me to discover

that EMI had approached Wood before Barbirolli who had,

comparatively recently, returned to war-scarred Britain from his

spell with the New York Philharmonic Symphony.

The symphony's recording

sessions were presided over by Walter Legge and the intrinsic sound

captured is much better rendered on the Dutton than on the EMI. From

this point of view Dutton Laboratories have done a better transfer

and remastering job than Peter Bown and John Holland for EMI

Classics almost a decade ago. Taking one example: the bed of 78 hiss

and burble, faithfully present in the middle background in the EMI,

has been lowered substantially. Miraculously cyclical disc rotation

blemishes have been neatly elided. Compare from 08.00 to 09.00 in

the first movement in the EMI as against the Dutton. There is

evidence here that the Dutton is the most solicitous and beguiling

transfer this recording has had. It makes you wonder what the next

generation of processing a decade down the road will have achieved.

The Dutton is a de rigueur

addition for all Baxians and an antidote to the sleepy sloppy school

of Baxian interpretation.

Copyright © Rob Barnett

_________________________________________________________________________

Review by Graham Parlett

This is one of the most

important historical issues of Bax's music to be released on CD.

Barbirolli's famous recording of the Third Symphony has been

unavailable for several years now, while the BBC recording of Eda

Kersey playing the Violin Concerto-only its second performance-has

never been commercially issued before in any format, though it was

broadcast in 1995 on Radio 3. Before reviewing the recording itself,

I thought it might be useful to give some information on the history

of the concerto, a work that was quite popular in the 1940s but has

since failed to find a place for itself in the concert hall.

Background

In November 1932 Bax was

engaged in orchestrating his Cello Concerto for the Spaniard Gaspar

Cassadó, and when he received a letter from the violinist May

Harrison asking him to compose a concerto for her, he demurred: 'I

don't feel that I could start something else in the thick of this

cello concerto', he replied. 'Besides violin and orchestra is I

think about the most difficult thing that a non-string player could

make a mess of. The standard is so high, remembering the Brahms

concerto.' (Incidentally, May Harrison had a permanent crush on Bax,

and one wonders what prompted his remark a few sentences later: 'Do

you really think men look their best in bed? How unexpected!!'.)

Although by this time Bax had

written at least seven works for violin and piano, including the

three published sonatas, he was himself a pianist and, apart from

some violin lessons as a child, had no practical experience of

strings: 'I could no more make a speech', he once wrote, 'than play

a stringed instrument.' Nevertheless, the idea of writing a Violin

Concerto, which May Harrison had first suggested, did finally come

to fruition a few years later, albeit in connection with another,

more celebrated virtuoso.

According to Lewis Foreman's

biography, Bax began writing his Violin Concerto in June 1936 and

completed the short score in October 1937, basing part of the slow

movement on his recently completed 18th-century pastiche Piano

Sonata in B flat ('Salzburg'). He finished the orchestration of the

first movement on 27 February 1938 in Morar, Scotland, and by the

end of March the work had been completed. The full score manuscript

bears a dedication 'To Jascha Heifetz' (not 'To Firenze', as given

in the CD notes), but this is omitted from the violin-and-piano

version published in 1946. Heifetz had published an arrangement for

violin and piano of Bax's Mediterranean in 1935, and it is possible

that he had then commissioned Bax to write a concerto for him,

though no correspondence between them seems to have survived to

confirm this suggestion, and it may be that he wrote it off his own

bat and then inscribed it to the great violinist, hoping that he

would take it up. Whatever the precise circumstances, it would

appear that Heifetz looked through the concerto but found it not to

his taste; it lacked the quality of showmanship that suited his

style of playing and there is no evidence that he ever performed it.

In a letter to Gramophone (April 1995, pp. 6 and 9) a reader

recounted the story told to him by an old orchestral player that

Heifetz had made a trial recording of the first two movements early

in 1937 with the London Symphony Orchestra and John Barbirolli and

that it was after his return to America that he decided not to

perform the work in public. However, as we have seen, the score was

not completed until March 1938 and there is no other evidence to

corroborate the story. In a review of the Chandos recording of Bax's

concerto, David C.F. Wright commented: 'An American friend of mine

who was close to Heifetz told me that it was the last movement that

was not liked.'

Having had the score rejected

by its dedicatee, Bax put it on one side and began work on other

projects, notably the Seventh Symphony, completed in January 1939.

But the outbreak of war put paid to creative activity, and it was

not until his appointment as Master of the King's Music in February

1942 that he was propelled into composition again, starting with his

first film score, Malta, G.C.

On 22 December that year

Arthur Bliss, then Director of Music at the BBC, wrote a letter to

Bax formally commissioning him to write a Violin Concerto, though it

is likely that Bliss already knew that such a work had already been

completed. The score received its first performance exactly eleven

months later, on 22 November 1943, at a St Cecilia's Day Concert,

with the violinist Eda Kersey accompanied by the BBC Symphony under

Sir Henry Wood. It is interesting to note, incidentally, that five

distinguished British composers all had recently composed violin

concertos performed within a few years of each other: Bax (1937-8,

played 1943), Britten (1939, played 1941), Dyson (1941, played

1942), Moeran (1937-42, played 1942) and Walton (1938-9, played in

London 1941). Bax's concerto was broadcast live on the BBC Home

Service and a recording is preserved in the BBC archives. A second

performance, this time with the BBC Symphony Orchestra 'A' conducted

by Sir Adrian Boult, was broadcast from the Corn Exchange, Bedford,

on 23 February 1944, and it is this live performance that is now

being issued. But time was running out for Eda Kersey, and five

months later, on 13 July, she died suddenly at the age of forty.

After her death, Bax's

concerto was taken up by other soloists, such as Frederick Grinke

and Marie Wilson, and indeed its popularity began to irk Bax, who

regretted its exposure at the expense of his symphonies. The work's

light-weight character came as something of a shock after the drama

of the symphonies. As William Mann put it: 'Bax's violin concerto

sprang surprises in plenty on those who attended its first

performance expecting to hear a thickly-scored, highly-coloured,

perhaps diffuse rhapsody-something like a long, accompanied

cadenza'. Bax himself clearly thought it was stylistically different

from many of his other works when he told Philip Latham that it was

'rather like Raff'. The unusual tripartite structure of the first

movement, labelled Overture, Ballad and Scherzo, also drew much

comment, though in fact it bears a vague resemblance to traditional

academic sonata form if we regard the Overture as the exposition of

the so-called first-subject group, the Ballad the second-subject

group, and the Scherzo a kind of development 'making mock of the

themes of the first part', to borrow from Bax's programme note.

'Finally', he continues, 'there are triumphant restatements of the

chief themes of the Overture and Ballad'-in other words a kind of

truncated 'recapitulation'. Although generally well received at the

time, not all critics have reacted positively to the work's charms,

and even the ardent Baxophile Peter J. Pirie could write of it:

'Some of Bax's worst faults are on display in this rather cheap

piece'.

In the years following Bax's

death (in 1953) the concerto fell into neglect, along with most of

his other music. On 6 February 1957, André Gertler with the BBC

Symphony Orchestra under Sir Malcolm Sargent revived it in a fine

performance at the Royal Festival Hall, an event fortunately

preserved on tape and thus my own first introduction to the work.

Hugh Bean and the BBC Welsh Orchestra under Vernon Handley broadcast

it on 24 June 1975, and it was also broadcast on 13 November 1980 by

Dennis Simons with the BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra under Raymond

Leppard, though neither performance did the score justice. (Simons,

by the way, is the only violinist to play the passage in the piano

score starting at bar 9 after letter (X), third movement, which is

actually a solo for the second trumpet mistakenly printed in the

violin part.)

On an absolutely sweltering

night in August 1983 Manoug Parikian and Bryden Thomson with the BBC

Welsh Orchestra gave a rather uninspired performance at a Promenade

Concert; in fact the most exciting feature was the chilling,

banshee-like sound suddenly emitted by a member of the audience as

she fainted from the heat during the Scherzo section of the first

movement. Ralph Holmes, who was a notable champion of the work, was

planning to record it in 1984 with Vernon Handley when a brain

tumour brought his life to a tragic and premature end. Three years

later, on 13 June 1987, Parikian's pupil Alan Brind, a Young

Musician of the Year winner, played it at a concert in Norwich

Cathedral with the University of East Anglia Student Symphony

Orchestra under Mark Fleming, reinstating the second of the two cut

passages in the slow movement. On 28 January 1990 John McLaughlin

Williams, with the Pro Arte Orchestra of Boston, gave an

exhilarating performance in what was believed to be the American

première, this time using Bax's final, cut version. Lydia

Mordkovitch's fine recording with the LPO under Bryden Thomson

followed in 1991, with the second and third cut passages reinstated,

and more recently Nigel Kennedy has expressed interest in recording

the work with Vernon Handley (see the interview with him in

Gramophone for December 2000).

Athough Bax's Violin Concerto

has been played more frequently than the Cello Concerto and the

Phantasy for viola and orchestra (another work championed by Ralph

Holmes), it has certainly not entered the repertoire in the way that

another attractive, warmly romantic work has. I refer to Samuel

Barber's concerto, which, incidentally, was given its UK première

by Eda Kersey at a Promenade concert in 1943; the two composers were

personally acquainted, and Bax is said to have admired Barber's

music. But then British violin concertos, apart from the Elgar, have

never been among their composers' most often performed works: one

thinks of Vaughan Williams and Britten among the more famous

figures, while the fine concertos of Stanford, Brian, Dyson, Moeran,

Stevens, Benjamin and Veale have fared no better, though at least

most of them have now been commercially recorded (the Veale only

very recently).

The score

There are three written

sources for Bax's Violin Concerto: (1) the full score manuscript now

in the British Library (Add. MS. 54757); (2) the published

arrangement for violin and piano originally issued by Chappell &

Co. Ltd. in 1946 and now available from the Studio Music Company;

(3) a copyist's score of the separate violin part with annotations

in Bax's hand, found inside a copy of the printed violin-and-piano

arrangement formerly belonging to the violinist Orrea Pernel, which

I bought from Travis & Emery in 1996. Bax's original sketches

and short score are lost except for a brief sketch for the opening

of the slow movement which can be found on the MS of the 'Salzburg'

Sonata.

In 1991, in preparation for

Lydia Mordkovitch's recording for Chandos, I spent many hours

collating a copy of the printed violin-and-piano arrangement with

the full-score MS and made many corrections to it that Bax had

failed to notice when he proof-read it. These ranged from missing

slurs to wrong notes and note-values. I also made a piano reduction

of the three cut passages that only appear in the MS and inserted

them into a copy of the published score, although a few notes in the

first passage were illegible in the photocopy I had been given and I

left them blank to be filled in by the Librarian at Chappell's Hire

Library, which he failed to do. (For anyone owning the

violin-and-piano score, it may be helpful to know that the cut

passages occur between bars 6 and 7 on p.32 (16 bars), between the

last bar of p.33 and the first of p.34 (12 bars), and between bars 4

and 5 of p.48 (43 bars).) But in any case, when I attended the

Chandos recording session at St Jude's Church, Golders Green, on 23

June, I found that my work had all been in vain: the soloist had

been sent an uncorrected copy from which to learn the piece (though

a photocopy of one of the three cut passages had been added), which

means that the work's only modern recording contains many

inaccuracies. These, I hasten to add, are not the fault of the

soloist, who recorded another of the cut passages at the session

having only set eyes on it a few minutes before. The question of

whether it is morally defensible to restore cuts made by the

composer can be argued over at length. It seems to me that the cuts

in both the Violin Concerto and Winter Legends improve the structure

of each work, and from that point of view I feel that they should be

made. Nevertheless, it is always interesting to be able to hear

passages that the composer later deleted, and nobody with an

interest in British music would now wish to be without, for

instance, the recently released original version of Vaughan

Williams's London Symphony; and it would fascinating one day to hear

the passages that Bax deleted from his full-score MS of the Third

Symphony.

The violin part that I later

bought from Travis & Emery is of great interest in that it

includes the three passages that were cut in the published version

and has expression and dynamic markings in Bax's hand that do not

appear in either the full score or the piano score. I have not so

far traced any performance by the former owner, Orrea Pernel, and am

inclined to think that it is the handwritten copy from which Eda

Kersey learnt the part three years before it was printed. A few

minor details support this suggestion. For instance, in her

recording Kersey plays the grace note in the second bar after letter

(G) in the second movement as an F sharp, and this is the note

written in the copyist's score and probably also in the full-score

manuscript, where it is not quite clear; in the printed score, it is

a G sharp. The three cut passages have fingerings pencilled in,

suggesting that the first play-through, at least, was complete.

However, a copy of the BBC recording with Wood conducting is

preserved in the National Sound Archive (ref. T11048W) and reveals

that the cuts had been made before the first public performance.

Whether they were made by Bax after a preliminary run-through with

piano or in consultation with Wood at an orchestral rehearsal is not

known. This world première, incidentally, is generally a slower

performance than under Boult, noticeably in the second movement and

the Slow Valse section of the finale.

There is no doubt that Bax's

Violin Concerto is in urgent need of a thorough textual overhaul:

the score hired out to conductors is a photocopy of the MS, which

itself is in poor condition; the orchestral parts are the original

1943 handwritten ones; and the printed violin part is riddled with

mistakes and lacks the three cut passages. Music publishers are

naturally more interested in making profits than in making sure that

their materials are accurate, and the chances of Warner Chappell's

producing a scholarly edition of the work are remote, though I would

leap at the opportunity of editing it myself if asked to do so.

The recording

The violinist Eda Kersey is

little known today but was much admired in her lifetime as both a

soloist and a chamber-music player. Born in Goodmayes, Essex, in

1904, she started learning the violin at the age of six, and gave a

concert performance of the first movement of Wienawski's Concerto in

D minor at ten-and-a-half. She made her London début at the Æolian

Hall in 1920, when she was sixteen, and her Proms début ten years

later playing the Beethoven concerto. In the early 1930s, together

with the cellist Helen Just, she became a member of Howard

Ferguson's piano trio, and she was also a member of the Trio Players

with Gerald Moore and Cedric Sharpe. She also played with Brosa,

Casals, Sammons and Suggia, and her repertoire included concertos by

Bach, Barber, Beethoven, Brahms, Delius, Dohnányi, Elgar,

Mendelssohn, Sibelius and Vaughan Williams. According to an article

by Albert Cooper in The Strad (May 1984, p.51), she has been called

the 'Kathleen Ferrier of the violin' and was renowned for the

lyrical qualities of her playing, her security in double-stopping,

the clarity of her passage work, and for her presence and composure

on the concert platform. Cooper also maintains that 'Bax was

inspired to complete his concerto after many years on hearing Kersey

play his sonatas'. This is not quite true-the score was complete by

March 1938-but it suggests at least that the composer saw her as the

ideal person to give the first performance of a work that he had had

languishing in his bottom drawer for nearly five years. Her sudden

death on 13 July 1944, only a few weeks after she had given a

recital with Kathleen Long at a National Gallery Concert, must have

been a sad blow not only for Bax but for the musical life of wartime

Britain.

Eda Kersey made a number of

commercial recordings, and a few other performances by her are

preserved in the National Sound Archive, but until now there were no

examples of her playing on CD. One feature of her performance of

Bax's Violin Concerto that immediately stands out is its fast tempi.

The outer movements are taken at a cracking pace, in sharp contrast

with some of the performances broadcast in the 1970s and '80s, which

were far too cautious and sedate, not to say dreary. I suppose it

could be argued that the opening orchestral introduction to the

second movement is a little too fast for an Adagio, almost as if

Boult found it rather dull and wanted to move on. (We should

remember that he was not one of Bax's greatest admirers, though he

was the dedicatee of the Sixth Symphony and their personal

relationship was always warm and friendly.) Nevertheless, he does

bring to the rest of the concerto a vigour and a sparkle that eludes

most other conductors, and there is no doubt in my mind that this is

how the concerto should be played. Eda Kersey's comparatively light

tone suits the work well, and the virtuosity of her playing yields

nothing to that of other, more famous names. She brings an

irresistible joie-de-vivre to the first movement's Scherzo and to

the dancing finale and is adept at subtle changes of mood, as in the

lusingando ('coaxing', 'beguiling') melody in thirds after the

energetic opening passage; other soloists slow down here to deadly

effect, but Kersey keeps the music moving without making it sound

rushed.

The quality of the recording

is astonishingly good for its age. There is little background noise,

and I even heard details in the work that I had not noticed before.

The orchestral sound is often quite beefy: the vamping chords just

before the first entry of the soloist, for example, have never

seemed richer or more incisive; there is a wonderfully perky oboe

solo in the Scherzo just after (BB); while the tenor drum's

unexpected and barbaric appearance at bar 9 after letter (F) in the

finale comes across with startling vividness.

The coupling, Barbirolli's

recording of the Third Symphony (produced by Walter Legge) is too

well-known to require any further praise. Bax attended the sessions,

and the performance certainly reflects his wishes to a large extent:

'These records were made after days of intensive rehearsal under the

personal supervision of the composer, who has expressed his entire

satisfaction with the performance and players' (His Master's Voice

Record Supplement, February 1944, p.2). Once again the Dutton

transfer could hardly be bettered, with the surface noise of the

original 78 rpm discs reduced to an absolute minimum, even revealing

the odd studio noise from those sessions of nearly sixty years ago

in the Houldsworth Hall, Manchester, which, as mentioned in the CD

notes, Bax found insufferably cramped and overheated. I did a direct

comparison with the EMI CD issued in 1992 (and soon deleted) and

noticed that the latter had significantly more background noise. I

am also glad to see that Dutton have reinstated the half-bar that

EMI carelessly left out of their CD reissue at one bar before figure

(5) in the slow movement, where there was a side break on the 78s. I

have long known this performance from those old discs, and it says

much for the Dutton engineers' skill that in many places I failed to

notice where the breaks originally came. As a matter of economic

interest, the original set of six shellac discs cost £1-19s-9d in

the old currency (i.e. approximately £1.99), which in 1944 had the

same purchasing power as about £54 today. In other words each disc,

playing on average for less than four minutes a side, cost the

present-day equivalent of about £9, a sobering thought for any of

us who are tempted to complain about the high price of CDs in the

UK.

This is a magnificent release

which is enhanced by Lewis Foreman's informative notes-he even names

the bassoon and horn soloists in the wartime Hallé Orchestra-and by

the striking booklet illustration aptly featuring a London Transport

poster of 1944. Warmest congratulations to Dutton. I hope that they

will soon be turning their attention to the Griller Quartet's

incomparable recording of the First String Quartet.

Copyright © Graham Parlett

|

|