|

|

|

Support

us financially by purchasing this disc from: |

|

|

|

|

|

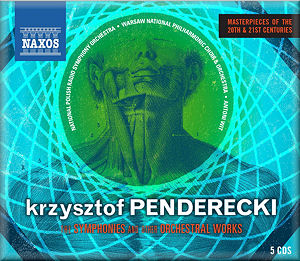

Krzysztof PENDERECKI

(b.1933)

The Symphonies and other Orchestral Works

Symphony No.11 (1973) [30:27]

Symphony No.2 1 Christmas (1980) [34:25]

Symphony No.3 1 (1988-1995) [44:24]

Symphony No.4 1 Adagio (1989) [30:42]

Symphony No.5 1 (1992) [37:37]

Symphony No.7 Seven Gates of Jerusalem2, 3 (1996)

[60:47]

Symphony No.8 Lieder der Vergänglichkeit2, 4

(2005) [36:28]

Aus den Psalmen Davids (1958) 2 [10:55]

Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima for 52 Strings1

(1960) [8:56]

Fluorescences for orchestra1 (1961) [14:52]

Dies Irae2, 5 (1967) [25:22]

De Natura Sonoris II for Orchestra1 (1971) [8:59]

Olga Pasichnyk3; Aga Mikolaj3; Micaela Kaune4

(sopranos); Agnieszka Rehlis4; Ewa Marciniec3;

Anna Lubanska5 (mezzos); Wieslaw Ochman3;

Ryszard Minkiewicz5 (tenors); Wojtek Drabowicz4

(baritone); Jaroslàw Brek5 (bass-baritone); Romuald Tesarowicz3

(bass); Boris Carmeli3 (narrator)

Olga Pasichnyk3; Aga Mikolaj3; Micaela Kaune4

(sopranos); Agnieszka Rehlis4; Ewa Marciniec3;

Anna Lubanska5 (mezzos); Wieslaw Ochman3;

Ryszard Minkiewicz5 (tenors); Wojtek Drabowicz4

(baritone); Jaroslàw Brek5 (bass-baritone); Romuald Tesarowicz3

(bass); Boris Carmeli3 (narrator)

National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra (Katowice)/Antoni Wit 1;

The Warsaw National Philharmonic Choir and Orchestra/Antoni Wit

2

rec. Grzegorz Fitelberg Concert Hall, Katowice, Poland, 16 September

(De Natura); 28-29 September (Symphony No.3); 27 October

(Threnody); November 1998 (Fluorescences); 17-18

May (Symphony No.5); 25-26 June (Symphony No.1); 25-27 August (Symphony

No.2); 8-10 September 1999 (Symphony No.4); Warsaw, Philharmonic

Hall Poland: 18-20 November 2003 (Symphony No.7); 8, 9, 11 March

(Symphony No.8); 30-31 August (Dies Irae); 27, 29 November

2006 (Aus den Psalmen)

NAXOS 8.505231 [5 CDs: 77:25 + 68:06 + 65:14 + 60:47 + 72:45]

NAXOS 8.505231 [5 CDs: 77:25 + 68:06 + 65:14 + 60:47 + 72:45]

|

|

|

Sometimes it can be very rewarding to be presented with a tranche

of music by a major composer that you know not at all. That

has proved to be resoundingly the case with this five disc set

of “orchestral” works by Krzysztof Penderecki. I use the inverted

commas advisedly since two of the symphonies are really major

choral/vocal works to which the composer has almost arbitrarily

appended the title ‘Symphony’. Indeed in the case of the Seventh

Symphony this occurred only after its premiere as an oratorio.

As this is a review of the five disc set which includes all

Penderecki’s completed symphonies to date I propose reviewing

them in symphonic rather than disc order. Aside, from anything

else I found, as a listener new to this repertoire, it was informative

and interesting to chart Penderecki’s development in the 32

years covered by the seven main works.

Before considering individual works a few other umbrella comments.

All the performances are conducted by Antoni Wit who aside from

being a conductor of exceptional breadth and skill also studied

composition with Penderecki. I have no idea what Wit’s own compositions

are like but that fact alone must assure the listener that here

is an interpreter with a close and profound understanding of

what makes the composer ‘tick’.

Wit conducts two orchestras; the first three, purely orchestral,

discs are played by the National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra

in Katowice whilst the final two choral symphonies are performed

by the combined forces of the Warsaw National Philharmonic Orchestra

and its associated choir. I will write more about the orchestras

later but suffice to say at this point that I have been greatly

impressed by the skill and dedication of both groups.

I was slightly surprised to realise that Volume 1 of this set

was recorded as long ago as 1998. In other words little more

than a decade after Naxos had entered the Classical Music marketplace

as a bargain basement label selling standard repertoire on carousels

in Woolworths, it was embarking on a major cycle of recordings

of this knotty stature. From the standpoint of another fifteen

or so years further on, this does not seem so remarkable but

I think it is important to mark just what a major artistic undertaking

this was and how triumphantly it has been achieved.

Special mention too for the technical teams involved. The three

Katowice discs were recorded and produced by the excellent Beata

Jankowska. Her name will be familiar to those who have collected

the critically acclaimed Mahler and Tchaikovsky Symphony cycles

again with Wit on Naxos as well as many other recordings too.

The former in particular will tax any engineer’s skills but

it has to be said that the complex textures and wide dynamic

range of the works presented here must have been as challenging

as any. Jankowska has produced discs that sound superb regardless

of any notional bargain price point.

Naxos, as is there wont with their boxed sets, have simply taken

the existing discs exactly as they are and put them in a cardboard

slip-case. The benefit for the collector is financial with the

five disc set available for around the £15.00 mark whilst the

same discs separately are about £6.50. So the set represents

roughly a 50% saving on the individual discs. There are other

recordings available – including some under the composer’s baton

– but I have not heard any of those so am not in a position

to make any comparative judgements.

Symphony No.1 dates from 1973 and was commissioned by

Perkins Engines of Peterborough England - still going strong

today. One rather wonders how many companies in recession-hit

2012 would consider such an investment even for a second. Yet

we should be profoundly grateful that they did since this prompted

or persuaded Penderecki onto a fruitful path.

Richard Whitehouse’s brief but very useful liner-note provides

excellent markers through the score for the first-time listener.

As will become clear, Penderecki underwent something of a musical

conversion between his first and second symphonies moving away

from the post-war Modernism of the 1950s and 1960s to embrace

something altogether more tonally-centred which has been labelled

‘neo-Romantic’. As ever, these labels can be as confusing as

they are enlightening. Suffice to say that the early works –

including the First Symphony - inhabit a world of unrepentantly

‘contemporary’ musical techniques where textures/sonorities

and gestures – rhythmic or harmonic - seem to take greater precedence

than the older values of form or melody. I use the word seem

with some care because Whitehouse usefully points out recurring

structural use of ‘A’ as a tonal centre and a walking string

line in the celli/bass parts that give the work formal coherence.

Certainly, it proves to be instantly engaging and for a half-hour

work played without a break one’s attention never wanders. That

being said, it is the textures and sounds Penderecki

draws from the large orchestra (triple wind, 5 horns, 3 trumpets,

4 trombones, tuba, 5 percussion, harp, celesta, harmonium and

piano plus strings) that resonate more than instantly perceivable

form or melody.

Having waited some forty years before tackling symphonic form

for the first time Penderecki wrote a Second Symphony

just over six years later. It was during those intervening six

years that Penderecki made the important compositional shift

from the essentially experimental to the neo-romantic. That

he started it on Christmas Eve 1979 might account for its occasional

subtitle - Christmas together with some fleeting rather

wan references to the carol Silent Night. It should

be noted that this title does not appear anywhere on the Schott

published score. Certainly it is not a work replete with "joy

to the world" inhabiting as it does a troubled and dark

emotional landscape into which brief flickers of familiar melody

end up casting as much shadow as they do light. Richard Whitehouse

provides another valuable note and he see this work as containing

presentiments of the strife suffered in Poland in the early

1980s with the brief success of the Solidarity Union. Whitehouse

characterises the work as a tribute to those who dared to challenge

the totalitarian State head-on.

By now Penderecki's musical vocabulary has become unrepentantly

neo-romantic and the music of this Symphony is more overtly

emotional than the earlier work. Certain Pendereckian symphonic

characteristics are beginning to appear already; a preference

for large single movement forms internally divided into more

traditional fast and slow sections is a key one. Symphony No.2

has three main sections which interestingly not only follow

a rough symphonic form but at the same time mimic a basic sonata-form

of exposition, development and recapitulation completed with

a final coda. The orchestra used is similar to the Symphony

No.1 requiring just one less percussionist and no piano or harmonium.

The sound Penderecki now draws from the players is quite different;

more weighty and certainly fuller.

Again, great praise to both players and the technical team for

a recording of wide range and telling detail. The brass have

some formidably demanding parts to play and they sound as impressive

as they are exciting. Central to the emotional impact of the

work is a brass-led alleluia figure that comes towards the close

of the opening exposition section [track 3 2:19]. Although no

reference as such is indicated, to me this has the spirit of

an ancient Polish knight's prayer very similar in its

emotional impact to that used by Panufnik in his Sinfonia

Sacra.

Penderecki's command of symphonic form is again displayed

when it becomes apparent that this hymnic phrase is derived

from the work's opening material. Further emotional and

musical resolution is found with the return of the alleluia

near the work's close [track 5 3:35] although this potentially

exultant ending is soured by an immediate descent into an abyss

of growling low brass and insistent timpani pedal notes which

at last dissipates to allow a final haltingly insecure reference

to Silent Night. The symphony ends - borrowing Whitehouse's

ideal description - in a mood of pensive resignation. Another

impressively powerful work receiving what seems to be a wholly

convincing performance.

The Third Symphony did not appear in its final form until

1995 although the final two movements appeared as a separate

piece at a festival in Lucerne in 1988. Still searching for

a definitively personal symphonic form Penderecki moved on from

the overtly neo-romantic 2nd Symphony to a style that sought

to synthesise elements of both the old and the challengingly

new. The Third Symphony is a big piece in every sense. Its five

movements last nearly forty-five minutes and Penderecki has

expanded his orchestra - still with triple wind - to include

a fourth (bass) trumpet and fourth trombone but now with an

even larger percussion section requiring nine players. More

impressive than its sheer physical scale is the assured way

in which Penderecki has fused traditional elements of the multi-movement

symphony with his own distinct musical and aesthetic language.

Even more than in the earlier works the virtuosity of individual

players in the ever-excellent Katowice orchestra is apparent;

special praise for the lead trumpeter in the extended, twisted

and convoluted 2nd movement solo [track 2 00:30]. Demonstration-worthy

engineering ensures that every strand of this complex and weighty

score registers.

While having written a stern work often heavy with foreboding

Penderecki seems to have thrown off the sheer weight of melancholy

that pervaded the Second Symphony. By dividing it into five

distinct movements the perception is of a greater emotional

range allowing more light and shade. The opening Andante

con moto emerges from the shadowy depths where an obsessively

repeating string pedal provides the base from which instrumental

figures grope upwards. Lasting less than four minutes this has

the sense of a prelude or preamble preparing the musical stage

for the drama to follow. The relative calm is dispersed in a

flurry of strenuous string and timpani activity that opens the

second movement Allegro con brio. Pitted against this

maelstrom are various solo instrumental cadenzas and short gestures.

Gradually the strings are replaced by competing tuned percussion

motifs. Excessive percussion writing can often seem rather vacant

and intent on making noise for noise's sake but here

both in intention and execution the effect is utterly compelling.

The movement is driven unrelentingly forward until we reach

a cor anglais cadenza of uneasy pastoral calm - again cruelly

written but stunningly played. The movement closes over tolling

bells and a reminiscence of the work’s opening low string figure.

This prepares the ground for the central Adagio. Here

Penderecki achieves a relative peace that has eluded him in

his symphonic writing until now. Long lyrical string lines weave

in and out of contrasting wind figures over a bed of long-held

string pedals and tubular bell rolls. Near the movement's

central point the calm is shattered by an eruptive brass statement

leaving the strings shuddering with shocked tremolandi. This

subsides as quickly as it emerged and the lyrical dialogues

resume. The obsessive aggressive repeated low D that opens the

fourth movement Passacaglia is - as described in the

liner - severe and ominous. Little wonder that film director

Martin Scorsese used this passage for part of his recent powerfully

oppressive Shutter Island. One assumes that the passacaglia

of the title is often unheard since many of the solo passages

are just that and have no accompaniment which would 'contain'

the harmonic fabric implied by the title. Instead continuity

is provided by the near ever-present pedal Ds and more quietly

insistent yet understated bells which seem to gain significance

within the work's structure as it progresses.

The closing Vivace movement revisits obsessively the

idea of pulsating low ostinati based on small melodic cells.

This time there is an unwavering driving pace to the music which

gives it a toccata-like quality. As with much of the symphony,

if one were able to give a tonal character it would be minor

key. Again solo cadenzas sit on a bed of orchestral texture

yet where previously these were essentially static in this movement

the underlying character is one of action. A central panel of

the movement has instruments working in pairs either alone or

in juxtaposition with other pairs. Gradually the momentum regains

the energy that opened the movement. This is maintained - with

a variety of dynamic and scale - for most of the remainder of

the work. From 9:30 the heavy brass joins and gradually the

music builds in power and pitch centres - gaining height from

the depths in which it has been gravitating to a rather perplexing

and abrupt slowing of the pace into the final soured major key

gesture with which it ends. Having listened several times to

the piece I still find this ending rather unconvincing especially

given the power of most of what has come before.

The Fourth Symphony - coupled here with the 2nd Symphony

- was composed and received its premiere in 1989 thereby actually

predating its predecessor. It was written as a commission to

mark the bicentennial of French Revolution. Again Penderecki

uses the single movement divided into five distinct parts. The

subtitle "Adagio" is somewhat misleading since one

could not say that the music is predominantly slow. The scale

is reduced - lasting just over half an hour. There’s a smaller

orchestra - similar wind and brass but with a smaller percussion

section and no 'extras' like celesta or piano

or even harp. There is a group of three off-stage trumpets which

adds an extra theatricality. By now "Pendereckian"

gestures are becoming more familiar - accompanied cadenzas and

a generally sombre indeed pessimistic mood pervade. Certainly

this is not music that offers easy solutions or 'happy

endings' for the listener. This symphony has the feel

of a work concerned more with a journey harbouring little or

no expectation of an arrival. Other commentators have evoked

Shostakovich's shade when discussing Penderecki and much

of the time I feel this is a very generalised comment at best

and at worst misleading - to neither composer's benefit.

Yet the bassoon recitative in this symphony's 3rd movement

(track 8 8:30) does indeed evoke the shell-shocked

grieving of the older composer's finest work.

As ever, and perhaps superfluously by now, praise to the orchestra

for some wonderfully expressive solos. Indeed this proves to

be one of the most compelling movements in this cycle so far

- quite literally at the heart of both this work and the seven

symphonies as they currently exist. Another Pendereckian finger-print

fugato follows - awkward and angular filled with obsessive unsettled

energy. Beata Jankowska creates another typically well-managed

sound-stage with the percussion convincingly placed and the

wealth of instrumental detail registering with exceptional clarity,

The offstage trumpets manically chase and echo their onstage

counterparts. The closing section revisits elements of the wind

soliloquies and remnants of the string fugatos with ghostly

trumpet fanfares. The music unwinds and fades away into a unison

before silence. No closure again but more compelling than the

end of No.3.

Barely another two years passed before Penderecki started on

his Fifth Symphony - does the number explain the rhythmic

use of Beethoven’s “fate” motif I wonder? - commissioned this

time to mark the 50th Anniversary of the independence

of Korea from Japan. This is the last of the instrumental symphonies

– No.6 is elusively described as “in progress”. There’s a ingle

movement form again the use of a large orchestra with quadruple

wind this time with an additional 4 trumpets in the hall. That

said there are ‘only’ four percussionists. Within the percussion

group Penderecki does stipulate what might be termed some Eastern

instruments but their presence could not be said to colour the

compositional choices made. It did occur to me that he occasionally

uses bells or gongs to mark musical paragraphs in the way Tibetan

temple bells mark the start of a new period of prayer or meditation.

Naxos have chosen not to divide the sections of the

work. This which plays continuously for a full 37 minutes even

though, paradoxically, the sub-divided ‘movements’ are more

clearly defined – even on a first listen – than some of the

earlier works.

Penderecki rarely – if ever – in the symphonies requires the

extended performance techniques of his orchestra that in many

ways define his earlier orchestral works. For sure the music

is complex and often very demanding indeed to play but he does

ask for non-standard modes of playing. That said, in this symphony

he returns to the juxtaposing of material, harmonic, rhythmic

or melodic, that harks back to the First Symphony and indeed

to earlier works. So the opening takes a harshly repeated single

note and contrasts it with a falling melodic line which is in

turn contrasted with a rising melodic line. The first five minutes

seem to lay out the musical material of the piece for inspection

and while not strictly cyclical Penderecki does return to this

basic fabric repeatedly. Around the five minute mark the violas

lead off a violently aggressive fugal passage. This is impressive

both as played and as written. Again as seems to be the norm

with Penderecki this conveys a very serious, almost intellectual

rigour without adding much in the way of emotion. Richard Whitehouse

in the liner-notes refers to a “Shostakovich-like irony” in

the handling of the central section of the work. I must admit

that this eludes me mainly because Penderecki never allows the

underlying mood to vary from the sobriety of his preferred style.

Without ‘lightness’ – sincere or satirical - there is little

contextual room for irony. For me the power of Penderecki’s

writing comes from the cumulative, unwavering preference for

what in other hands might seem like a limited emotional palette.

This staunch refusal to relax an iron grip on the music means

that when very occasionally a ray of light does pierce the gloom

it is as surprising as it is welcome. Very briefly, like a false

dawn, there is an intriguing passage which seems to echo Nielsen’s

Helios Overture but the hope it might represent is

extinguished almost as soon as it is expressed. A return of

the fugal/scherzo material leads to the mightiest climax of

the work near the thirty minute point. As ever the Katowice

brass are massively impressive.

I’m not sure exciting is the right word but this is music of

exceptional power and impact. The closing pages revisit fragments

and elements of the music that has already been explored and

expanded upon. More exceptional work from the oboe and cor anglais

in particular mark another of Penderecki’s favoured cadenza-soliloquies.

Just as the assumption is made that the work will close with

a sense of repose a last vehement string outburst echoes the

hammered repetition of the opening albeit on a different pitch

centre as if to reinforce the impression of ‘not-quite-cyclical’.

Even on my brief knowledge and acquaintance with this music

I found this work to be initially knotty but increasingly impressive.

By the time Wit came to record the last two symphonies he had

moved on to become the Managing and Artistic Director of the

Warsaw Philharmonic so no surprise that they should feature

as the chosen orchestra. A different technical team; Andrzej

Sasin and Aleksandra Nagórko were given the task of committing

these very large-scale works to disc. Sasin was on the desk

for the recording by these same forces of Janácek’s Glagolitic

Mass which impressed me less than other reviewers. No complaints

this time – the forces Penderecki deploys are vast even by his

standards; 5 soloists (2 sopranos) plus narrator and a large

choir - the score states 3 choirs and indeed 3 separate ones

took part in the first performance. There’s a huge orchestra

with again quadruple wind and brass, including the rare bass

trumpet, piano, celesta and organ plus strings. Twelve percussion

are split into four groups. The icing on the instrumental cake

is an off-stage instrumental group of another 4 clarinets and

4 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 4 trombones and tuba. Curiously,

as is often the case in Penderecki’s work, the listener is not

often overwhelmed by the sheer scale and power of the writing.

The number of instruments is more to allow a variety of texture

and spatial presentation rather than simple full-frontal assault.

All credit to the technical team who provide a sound picture

combining clarity and well-defined positioning as well as power

when required. My one little query is whether the choir has

the sheer numbers available to match the few occasions they

are pitted against the full orchestra. For all the good work

of the engineers they are rather swamped.

Richard Whitehouse again supplies the liner. He sees the work

as representing a fusion or confluence of the twin threads of

choral and symphonic composition. Hence the equivocation between

its original description as an ‘Oratorio’ and the later appending

of the title ‘Symphony No.7’ when it received its Polish

premiere. The Symphony/Oratorio is sub-titled The Seven

Gates of Jerusalem. Although there are eleven gates

in the walls of the old city as built by Suleiman

the Magnificent only seven are open with the eighth being

reserved – in Hebrew tradition – for the Messiah. No real surprise

therefore that “7” takes on a structural quasi-ritualistic significance

in this work. There are seven movements and 7-note phrases and

motifs bind the structure. Much as these motifs impose themselves

on the listener even on initial acquaintance there is another

quality that separates this work from the preceding symphonies:

radiance. Penderecki allows light into this score in a way that

has been conspicuously absent before. For sure it is still an

often stark indeed gaunt work but critically the presence of

soprano voices, both in the choir and as soloists, alone or

duetting, lifts the weight of stark sobriety that has marked

many of the earlier works. An example of this is that it opens

with a firmly unison C and closes with a sustained unclouded

and unequivocal held chord of E. This is quite without the harmonic

ambiguity that shrouds/defines the other symphonies.

The singing is uniformly excellent – perhaps the choir sopranos

“splash” a couple of their entries but overall it is impassioned

and committed singing. If that is true of the choir it is even

more so of the soloists. The fact that four of the five are

native Poles - soprano Olga Pasichnyk is Ukrainian - gives both

the sound they make and style a thoroughly idiomatic feel. My

only gripe is the Naxos standard practice of making the text

only available online – for the sake of another page in the

booklet I don’t want to have to print off a sheet that won’t

then fit in the jewel case or box. For those willing to have

a computer to hand while listening Penderecki’s publisher Schott

offer a major bonus. The entire score can be viewed as a scrollable

pdf. With such a rich and complex score it is fascinating

to see how the parts on the page translate into sound. Penderecki’s

great skill here – and in many of his other vocal works in particular

– is to achieve a fusion of ancient and modern. The musical

vocabulary is patently ‘modern’ yet its animating spirit is

ancient and timeless. Much of the music seems ritualistic and

potent with extra-musical meaning. Much of the text is taken

from the Psalms with the rest excerpts from the Old Testament.

The first and last movements frame the work with imposing music

of considerable impact and a spirit of some grand pontifical

procession. The writing is monolithic and spare in its use of

textures or contrapuntal writing. What we hear are blocks of

sound/instrumentation set in opposition to each other. The second

and fourth movements make prominent use of the repeated 7 note

phrase alongside other Pendereckian gestures of slowly descending

scalic figures in the strings as well as throbbing timpani.

The presence of five soloists, as with so much of this work,

seems rather luxurious since none have overly large roles but

Penderecki uses them to telling effect. The second soprano in

the second movement Si oblitus fuero tui, Jerusalem

is a highlight. The third movement De profundis is

set for the choir alone. I did wonder if there was just a hint

of caution in the singing that robbed it of the hushed intensity

the writing would seem to demand. By its nature it is horribly

exposed writing and the choir are very fine but in my mind’s

ear I could imagine it even better. The first four movements

are all self-contained whilst the final three run together.

The framing music of the 5th Gate Lauda Jerusalem

is the only sustained scherzo-like music in the work. Antiphonal

percussion groups are the driving force behind an exciting toccata-like

movement. Again the sopranos prove a little fallible in ‘pinging’

out high-lying notes from nowhere but this does not unduly detract

from the music-making. This is the longest single section of

the work – running to over seventeen minutes with two toccata-scherzo

sections framing a pastoral central panel featuring some beautiful

orchestral playing. An extended horn solo in particular lingers

in the memory. The penultimate gate is striking for the introduction

of a sepulchrally-voiced narrator sounding rather like one imagines

an Old Testament prophet did haranguing the cowed masses. The

instrumentation here is very striking with static string and

brass chords punctuated by percussion gestures marking out the

sections. The ‘only’ melodic material is given to the previously

mentioned bass trumpet which is meant to represent the voice

of God. At the climax of the movement the choir enters with

the seventh and final gate which builds impressively featuring

the entire performing group who revisit material both literary

and musical from earlier in the work. Apart from a muted section

towards the end the work closes with the powerful affirmation

in bright E major.

The celebratory nature of the work – written to mark Jerusalem’s

3rd Millenium – dictates the impractical near-profligate

scale of the writing. You can imagine programme planners having

nervous breakdowns trying to stage this work; at ‘just’ an hour

long it’s too short for an entire concert but what on earth

to programme with it. I suspect a modicum of logistic pragmatism

has robbed this performance of the extra choral forces that

would have made this recording even more impressive than it

is – which, to be honest, is pretty impressive. Again a major

feather in the Naxos cap for making music of this complex quality

available in such a fine and affordable recording.

So to the Eighth and last - to date - Symphony

… or perhaps not. The performance on this disc is of the original

2005 score consisting of twelve song settings lasting around

36 minutes. Referring to Schott's site reveals - they

provide another online viewable score - a 2007 revision. This

adds a further three songs and apparently extends the running

time by nearly twenty minutes. As and when Naxos decide to record

this revision time will tell. What is unclear is whether this

'original' version is still deemed legitimate

or has been superseded by the expanded revision. Curiously Schott's

site lists this Naxos recording without making any mention of

this question of edition. Obviously, my comments relate to the

original version as recorded here.

From the very opening bars it is clear that Penderecki has reinvented

his compositional persona once again. This work has few if any

of the epic gestures of the 7th Symphony. Also there are - until

the closing sections - few of what I might term typically Pendereckian

gestures. Texts again are available on-line only. The feel,

for want of a better description is of post-modern-impressionism.

By choosing to set, in their original language, Romantic German

poets the composer creates a parallel with works such as Zemlinsky's

Lyric Symphony albeit refracted through a lens of a

contemporary music idiom. The scoring too is more pointillist

and subdued. Likewise, most of the movements are brief. Only

the twelfth and last breaks the five minute barrier. Although

Penderecki uses a substantial orchestra - again it is not clear

from the Schott's listing whether the instrumentation

was expanded during the revision - its use is carefully controlled.

Only in the final movement is it for the first time that all

three soloists, choir and orchestra join forces. The title translates

as "Songs of Transience" and indeed muted regret and

loss do permeate the music. Penderecki consciously seems to

focus more on lyrical beauty of lines. The performers are once

again excellent. Two of the three soloists took part in the

world premiere. The one who didn't, soprano Michaela

Kaune, is fearlessly brave in her tackling of the angular and

widely spaced lines. The Warsaw Philharmonic Choir are in fine

form too. Listen to the very end of the work; an extraordinary

effect with the choir executing a slow controlled glissando

slide upwards disappearing into the musical mist. In this original

version I like very much the way the full forces are saved for

this final movement. In the revision the ‘new’ 3rd

movement is a setting of Brecht which uses all the vocal forces.

Penderecki returns to some of his more characteristic traits

as though telling us that for all the experimentation earlier

this indeed is his ‘true’ self. The agitated string lines conform,

his presence as do the last of his cadenza-soliloquies here

again allocated to the garrulous bass trumpet which made such

a sonic impact in the previous symphony. Overall, this is the

most overtly beautiful and reflective of the cycle.

One of the things Naxos got right early on was the appropriateness

and interest, as well as value, of the couplings. So it is with

these discs. Three of the five contain symphonies alone. The

remaining two have very valuable couplings. The earliest of

those is the 1958 Aus den Psalmen Davids which

is one of the works accompanying the 8th Symphony.

This setting of four Psalms is palpably early. The instrumental

group of two pianos and eight percussion echoes Stravinsky and

even Orff yet with seeds of the mature composer already evident.

There is particularly strong singing from the Warsaw choir here.

The contrast to the late symphony could barely be greater and

as such makes for a fascinating coupling.

Sandwiched between the two is a setting of the Dies Irae

from roughly a decade later before Penderecki had embraced neo-Romanticism.

Again for a short(ish) work Penderecki requires a large orchestra:

at least 3, often 4 wind and brass of each instrument, 8 percussion,

harmonium and piano. The strings are represented by cellos and

basses alone perhaps to emphasise the “de profundis” nature

of the work. Having made the journey with Penderecki through

his symphonies I must admit to finding his earlier incarnation

less appealing but this is a starkly atmospheric work with voices

appearing out of the musical gloom. Penderecki makes far greater

use of extended vocal techniques in this work with the chorus

muttering obsessively and clustered chords set in opposition

to explosive orchestral gestures. Again, the technical team

have to be praised for the clarity the recording has from the

faintest swish of a tam-tam to great walls of apocalyptic brass.

As musical theatre these are undoubtedly high-impact effects,

perhaps reflecting Penderecki’s other great interest in music

for the stage. However how lasting these make the music I’m

not so sure. Certainly, from a viewpoint of barely 45 years

later this kind of ‘cutting-edge’ modernism seems rather dated

now. Interesting in placing the composer on an evolutionary

path but of less enduring worth than much of his later music.

The earliest instrumental work included in this set is the famous

Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima for 52 Strings.

With such an evocative and indeed emotive title I was interested

to read that Penderecki considered initially titling it rather

baldly – in the style of Cage – 8’37”. Which rather begs the

question of what we as listeners ‘expect’ of a piece on the

strength of its title alone. Penderecki in the liner is quoted

as saying it was only after the first live performance that

he perceived the emotional charge in the work which caused him

to “search around” for an association before alighting on the

current title. Coming to the work hard on the heels of the later

symphonies is something of a shock – and in the reverse way

to his first supporters who felt his move to neo-romanticism

‘betrayed’ this earlier aesthetic. Putting to one side the title

– which I feel can blur the original aim of the work - this

is a classic example of contemporary composition from the late

1950s into the early 1960s. On a structural level it juxtaposes

the opposites of total freedom: chance or aleatoric techniques

with the very controlled demands of serial composition. More

immediately striking is his use of string sonority; one might

say anti-sonority since this work is a study in making non-typical

string sounds on stringed instruments. What lifts the work away

from the great mass of the music of this period is that Penderecki

– whether by accident, as it would seem from the above quote,

or design allowed an emotional element to invade the music.

I have seen other reviews that prefer the composer’s own recording

on EMI. I cannot make that judgement not having heard it but

this would seem to be a committed performance in its own right.

The irony is that in seeking to break free of the traditions

of both composition and performance works such as the Threnody

and indeed the other two fillers here created a new brand of

avant-garde formalism that was as hard to break free from as

the earlier one had been. Witness the fury within the contemporary

music community that Penderecki’s first forays into more ‘traditional’

styles provoked.

Fluorescences dates from a year after the Threnody

and expands the field of sonorities and instrumental textures

available by writing for the kind of large orchestra that typifies

the later symphonic works. When I say large orchestra in this

case I mean quadruple wind, six horns, four trumpets, three

trombones and two tubas, six percussion including a typewriter

and siren, piano and strings. Post-Satie I am not sure I can

ever take a score which contains sirens and typewriters wholly

seriously. The liner writer – Mieczslaw Tomaszewski – sees this

as an attempt to move beyond “the sphere of musical sound into

that of purely acoustic phenomena known from the modern world

at large”. Penderecki wrote in the concert programme for the

first performance: “In this composition, all I am interested

in is liberating sound beyond all tradition.” Certainly it has

the feel of Musique concrète transcribed for orchestra.

Whether or not this style of composition appeals will depend

on just how interesting and engaging you find such experiments

in orchestral timbres. Personally they pass me by except on

a level of having my curiosity piqued as to how any particular

sound is generated. This is not a work I can ever imagine feeling

‘in the mood’ for ever again. It is only fair to praise the

huge dynamic range of the recording and the precision, as far

as one can tell, and commitment of the playing.

The final work is De Naturis Sonoris II which

dates from a full decade later – much closer to the stylistic

schism. Certainly one can hear this as a way-station between

the experiments in sonority alone of the early works and the

music written from the 2nd Symphony onwards. The

writing is less self-consciously sensational/effect-driven although

still dominated by musical gestures born of extended playing

techniques.

Naxos has now produced some 18 or so discs of Penderecki’s orchestral

and choral works. This shows a stunning commitment to the music

of a major contemporary composer. I was trying to form an opinion

of which work impressed me the most and then realised that it

was the work I was currently listening to. This is music that

makes demands of both the listeners and certainly the players.

I am not sure I could categorise it as ‘enjoyable’ as such but

rewarding and fascinating and richly inventive for sure. In

fact it is exactly the kind of music that needs to be available

on disc to allow the listener to penetrate its complex depths

over time and repeated playings. Many the composer who laments

being able to have his music easily available to the general

listening public and when it is rarely can it be found in performances

as convincing and dedicated as those here.

An artistic statement of impressive intent and compelling execution.

Nick Barnard

|

|