|

|

|

alternatively

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

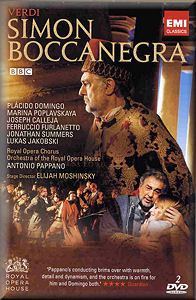

Giuseppe VERDI

(1813-1901)

Simon Boccanegra - Melodrama in a Prologue and Three

Acts. (Revised 1881 Edition)

Simon Boccanegra, a sometime corsair and Doge of Genoa – Placido

Domingo (tenor); Maria Boccanegra, Simon’s daughter known as Amelia

Grimaldi - Marina Poplavskaya (soprano); Jacapo Fiesco, a Genoese

nobleman - Ferruccio Furlanetto (bass); Gabrielle Adorno, a Genoese

gentleman in love with Maria – Joseph Calleja (tenor); Paolo Albiani,

a courtier – Jonathan Summers (baritone); Pietro, another courtier

– Lukas Jokobski (bass)

Simon Boccanegra, a sometime corsair and Doge of Genoa – Placido

Domingo (tenor); Maria Boccanegra, Simon’s daughter known as Amelia

Grimaldi - Marina Poplavskaya (soprano); Jacapo Fiesco, a Genoese

nobleman - Ferruccio Furlanetto (bass); Gabrielle Adorno, a Genoese

gentleman in love with Maria – Joseph Calleja (tenor); Paolo Albiani,

a courtier – Jonathan Summers (baritone); Pietro, another courtier

– Lukas Jokobski (bass)

Orchestra and Chorus of The Royal Opera House/Antonio Pappano

Directed by Elijah Moshinsky. Set Design by Michael Yeargan. Costumes

by Peter J Hall

rec. live, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, 2, 5, 13 July

2010

Region free NTSC Colour. Filmed in HD 50i 16:9 widescreen. For playback

on all NTSC and PAL systems worldwide.

Sound formats, LPCM Stereo. Dts 5.1 surround

Booklet essay and synopsis in English, French, German and Spanish

Subtitles for introduction and bonuses in Italian (sung language),

English, German, French and Spanish

EMI CLASSICS 9178259

EMI CLASSICS 9178259  [2 DVDs: 171:00 including bonuses]

[2 DVDs: 171:00 including bonuses]

|

|

|

It was during Verdi’s presence in Paris in 1855 for the production

of Les Vêpres Siciliennes that he accepted a commission

from the Teatro la Fenice in Venice for the 1856-57 season.

He decided on the subject of Simon Boccanegra, based

like Il Trovatore on a play by Guttiérrez. It was ideal

for Verdi, involving a parent-child relationship and revolutionary

politics in which he had always involved himself in occupied

Italy. Given the political background of the subject, and despite

the action being set in 14th century Genoa, the censors

gave Verdi and his librettist, Piave, a hard time. The composer

held out and the opera was premiered on 12 March 1857. It was,

in Verdi’s own words “a greater fiasco than La Traviata”,

whose failure could be attributed to casting and was quickly

reversed. The critics of the time wrote about the gloomy subject-matter

and the lack of easily remembered arias and melodies. A production

at Naples went better, but that at La Scala in 1859 was a bigger

disaster than Venice. The composer had moved his musical idiom

much too far for his audiences and he wrote, “The

music of Boccanegra is of a kind that does not make its effect

immediately. It is very elaborate, written with the most exquisite

craftsmanship and needs to be studied in all its details.”

Verdi’s regard for his composition, and he was his own sternest

critic, meant that although the work fell into neglect, the

possibility of revision and revival was never far from his mind.

In 1880 he had written nothing substantial since his Requiem

in 1874 and no opera since Aida ten years earlier. His

publisher, Ricordi, raised the subject of a re-write of Boccanegra.

Although in private he was seriously considering Boito’s proposals

for an Otello opera, in public he gave the impression

that he had hung up his pen. When Ricordi told Verdi that Boito,

who was providing him with synopses and suggestions for Otello,

would himself revise the libretto, the composer agreed to undertake

the task. The secret project, code-named ‘Chocolate’, in fact

the future Otello, was put on hold. The revised Simon

Boccanegra was a triumph at La Scala on 24 March 1881 and

it is in this later form that we know the opera today and which

is featured on this recording.

Those who are conversant with Verdi’s opera, but not up to date

with the goings-on in the opera world, might look askance at

the casting. A tenor singing this title role? Well yes, although

not many other so-called tenors would think about it. But, having

more or less met every other tenorial challenge in the repertoire,

around one hundred and forty roles at the last count, and recorded

most of them, he, pushing seventy, has been looking around for

new challenges rather than resting his vocal chords. Domingo,

like Bergonzi and others, started off as a baritone and in the

early nineteen-nineties recorded Figaro in Rossini’s Il Barbiere

for DG. However, there is a massive difference between the

demands of that lyrical baritone role and the title role in

Boccanegra, one of Verdi’s most dramatic. Although he

could always lighten his tone for the likes of Nemorino in Donizetti’s

L’Elisir d’Amore whilst contemporaneously singing Verdi’s

ultimate tenor challenge, Otello, in the heavier roles

he undertook Domingo’s voice always had a baritonal hue and

strength at the bottom of its range. That said, and whatever

its baritonal strengths, Domingo’s voice simply cannot bring

the necessary vocal heft to the big dramatic outburst in the

Council Chamber scene when Boccanegra seeks to dominate the

assembled crowd as he sings Plebe! Patrizi! Popolo (Disc

1 CH.19). Likewise when Boccanegra then circles and causes Paolo

to curse Amelia’s abductor, in fact himself (CH.20). This latter,

in particular, should send a tingle of fear down ones spine

and, at least vocally, it does not although with Domingo’s acting

it has its own similar effect. But here is also the paradox

in his performance. As an acted portrayal Domingo’s Boccanegra

is among the finest on record despite his not have the sheer

vocal heft and baritonal depth that Verdi envisaged. Doubtless

this owes much to his singing of the role in Berlin, Milan and

New York before arriving to sing in London. Add his normal meticulous

preparation for any role, and particularly a new one, and the

outcome is reflected in his assumption. Domingo conveys the

totality of the character in his demeanour and acting and also

vocally in the many more lyric pages of the score. Overall,

and putting aside the issue of baritone or tenor, Domingo gives

a penetrating and convincing interpretation of one of the great

Verdi roles.

Among the most lyric parts of the role of Boccanegra are in

the two recognition duets: that between the Doge and his daughter,

and no composer does father – daughter duets better than Verdi

(Disc 1 CH.13), and that with Fiesco in the final act (Disc

2 CH.14). Verdi used to spend every winter in Genoa and in this

production would hardly recognise the venue that is so beautifully

characterised in the music of the prelude to Act One and Amelia’s

aria that follows (Disc 1 CHs.8-9). The rather large spaces

militate against the poignant intimacy of the first of those

duets and where the two realise their relationship. In the second

duet with his daughter in act two, when Amelia pleads for clemency

for Adorno, a sworn enemy of Boccanegra, Domingo is a drawback

although, as he melts before her pleas, the lyricism becomes

dominant. As Amelia, Marina Poplavskaya, Elisabetta in the recently

issued DVD of the 2008 performances of Don Carlo (see

review),

is an appealing stage presence, good actress and secure vocalist.

If she doesn’t match Kiri Te Kanawa, who I saw in an earlier

production in the early 1970s and where the sea was more appropriately

present in the prelude to Act One, few others have done so since.

In those performances I was lucky enough to see the non-pareil

Boris Christoff as Fiesco, the only Verdi role apart from Philip

in Visconti’s Don Carlo in which the great Bulgarian

was cast at Covent Garden (see review),

and also Ruggero Raimondi. On this occasion Ferruccio Furlanetto

matches neither of them, nor is he secure vocally in the prologue

aria Il lacerato spirito (Disc 1 CH.4) as he was as Philip

in the 2008 Don Carlo recording. He does improve in sonority

and steadiness and is more impressive in Act Two as he faces

the evil Paolo (Disc 2 CH.3) and in the confrontation and reconciliation

with the dying Boccanegra in the final act (Disc 2 CHs. 11-18).

As Amelia’s lover, Gabriele Adorno, Joseph Calleja sings with

virile expressive lyric tenor tone. His rather chunky appearance

militates against the portrayal of the ideal ardent lover. Jonathan

Summers as the scheming and lusting Paolo, who poisons Simon,

rather over-eggs the cake with an excess of eye-bulging to go

with his rather dry tone.

The Royal Opera Chorus and Orchestra under Antonio Pappano deservedly

share the limelight with Domingo, the conductor seeming to have

a natural flair for Verdi’s drama with a fine balance between

the lyric and more dramatic parts.

The accompanying leaflet has an essay by Anthony Alabaster and

a synopsis in English, French and German. The essay titled Citizen

Verdi, seeks to draw a link between the composer’s views

and involvement in Italian politics and the influence on various

operas, particularly this one. Although informative, the space

might have been better used for the majority of purchasers by

the inclusion of a Chapter Listing and Timings; their

absence is, I suggest, a disgrace!; ships and tar come to mind.

For readers’ information these are as follows: - Disc 1.

Prologue (CHs.2-6); Act One Scene One (Chs.8-15); Act One Scene

2, The Council Chamber scene (CHs. 17-20). Disc 2.

Act Two (CHs.2-9); Act Three (CHs.11-18). In between the acts

and scenes there are brief behind-curtain views and comments

by Pappano. A more extensive bonus of two titles, Working

with Placido Domingo and Rehearsals with Elijah Moshinsky

are contained on Disc 1 (CH.7): nearly four minutes and six

respectively. The advertising blurb says there is an additional

audio function that features introductions to each of the opera's

scenes (in English with subtitles); it escaped my somewhat irritated

search unless they mean the brief interval visits behind the

scenes I refer to above.

Robert J Farr

|

|