Other Links

Editorial Board

- Editor - Bill Kenny

- London Editor-Melanie Eskenazi

- Founder - Len Mullenger

Google Site Search

SEEN

AND HEARD INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITION REPORT

The Korngolds - Cliché, Critic and Composer:

28 November 2007 to 18 May 2008, Palais Eskeles, Jewish Museum,

Vienna (JFL)

The Korngold exhibition, based on a concept of Michael Haas (known

to classical music aficionados who read the small print in liner

notes as the producer of Decca’s “Entartete

Musik” series), shows us the life of Korngold and his father

from the earliest days until the composer's death in 1957,

dividing it more or less into seven stages and eight rooms. The

influence and power of Julius is illustrated with facsimiles of

the Neue Freie Presse (where Korngold had the lower third

of the first three pages (!) to write about whatever he chose) and

loud interjections of some of Korngold’s more pointedly phrased

strong opinions, via speakers that interrupt everything you might

try to do. Even three rooms further ob, you can still hear his

cantankerous howling about atonal music. That you couldn't escape

his opinions and ideas – not in Vienna of the time, at any rate –

is the deliberate, unsubtle and well-made point.

A myriad of interesting information can be found in this lovingly

presented exhibit as well as the thorough 200 page catalog that

comes with a CD of important or personal excerpts of Korngold’s

music and his own playing. Curious factoids emerge: Korngold’s Cello

Concerto for example, was premiered by the Hollywood String

Quartet’s Eleanor Slatkin – while she was pregnant with Leonard

Slatkin’s little brother Fred (Zlotkin). (Hence Korngold’s joke of Allegro con embrio.)

Erich Korngold in 1910 (Age 12)

“Korngold 101” is easily encapsulated in the words: precocious

teen and Wunderkind who composed music too beautiful

to be taken seriously at a time when modernism swept the cultural

stage. A composer of highly successful film music in his years in

Hollywood – and consequently snubbed by the “real classical music”

‘elite’. That’s good enough for a start – but just how much

more complicated, conflicted, twisted, and interesting Korngold’s

story is can be experienced at the current exhibition at the

Jewish Museum in Vienna that will run through May 18th.

The first point is made by the exhibition’s title: “The

Korngolds”. This is not about Erich Wolfgang Korngold alone,

but in almost equal measure about his father Julius Leopold

too. (Little Erich was given his middle name in honor of Mozart

–which considering his father’s middle name and the path that

Erich would take, is a touching bit of irony.)

In order to understand Erich Korngold’s situation as a composer in

Vienna, it is essential to have a grasp of just how dominant a

figure his father was. Chief music critic for the

Neue Freie Presse and successor to Eduard Hanslick, he

commanded not just the most important position in Viennese music

criticism, he was the arbiter of what was good and

bad: in essence he was the pope of musical taste. Not quite able

to speak ex cathedra, perhaps, his word carried weight, so

much weight indeed, that his opinions could make artistic

life in

Vienna

impossible for all those arousing his ire. In that sense,

Julius Korngold not only shaped the musical life of

Vienna

but also of Berlin – to which all those who could not

get a leg on the ground in hostile Vienna, duly fled.

It is one of the most beautiful ironies in music criticism that

there were never before nor ever after classical music critics who

prepared themselves more diligently for their reviews than

Hanslick and Julius Korngold. Both were more than

knowledgeable about music, music theory, and the work they were

going to review. Whenever possible, every new work was played

through – several times on the piano and painstakingly analyzed

before being reviewed. Yet, despite this profundity and

seriousness in preparation and self-perception, neither Hanslick

or Korngold nor most of their erudite contemporaries were – amid

much very perceptive criticism – able to overcome polemical and

ideologically tainted attacks on what they thought “should not

be”. Those of Hanslick’s judgments that now seem ill-considered

(Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto, Wagner, etc.) are more famous than

his ample insight. Korngold loved everything that was in any

way related to Gustav Mahler and otherwise more or less hated

everything that Hanslick would not have liked either.

Being the son of the main music critic in the most important city

for classical music, and also one of the greatest composing

prodigies in music history, was another cute twist of fate for

Erich Korngold. Korngold Sr. didn’t trust his potential bias at

first and sought the opinion of 40 leading critics everywhere

except Vienna to judge his 11-year old son’s ballet piano score to

The Snowman. The responses ranged from baffled enthusiasm

to bewilderment. One critic in Budapest was so enthused, that he

went public with his ‘finding’ – and before long (against the will

of Papa Korngold), The Snowman was given a big premiere in

a gala performance honoring the Emperor’s name day (October 4th,

1910).

Julius Korngold

Eric Korngold’s (greatest, or at least biggest) opera Das

Wunder der Heliane (Decca’s re-issue of which I recently

reviewed) gets its own room – which might seem rather much to us,

if we don’t know the work or how important it was at its time. It

was given 45 performances between the two opera houses in Hamburg

and Vienna. Posterity has obscured our view of Das Wunder a

little with the contemporary and greater success of Krenek’s Jonny

spielt auf, but the two operas originally pitched against each

other as equals. The monopolist (and originally state owned, Ed)

manufacturer Austrian Tabacco issued two cigarette brands:

an unfiltered brand named Jonny – and the nicely packaged,

filtered and perfumed cigarettes called Heliane. With the

economics of smoking mimicking art, Jonny is still

available, and Heliane, not.)

Not the least to – temporarily – escape his unbearably overbearing

father, Erich Korngold ‘fled’ to Hollywood for one season where

Max Reinhardt, his collaborator on many Strauss-Operetta projects,

persuaded the composer to work with him again, this time on Warner

Brother’s Midsummer Night’s Dream. Once Hollywood had

noticed Korngold - at his arrival easily the most talented

musician to work in film - his future options looked bright

when he eventually had to leave Vienna not to escape his father’s

influence (Julius joined Korngold and his wife, Luzi at the last

possible moment) but Hitler. His career for film is well

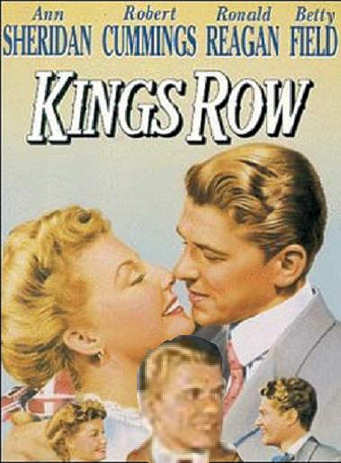

known and well documented in the exhibit. The Sea Hawk, Captain

Blood and Robin Hood are all there – as is

Kings Row which was of course the break-through hit for the 40th

President of the United States.

When Korngold died on November 29th in 1957 the program

of the memorial concert at Schoenberg Hall, University of

California (one of several items lent by the Library of Congress’s

Music Division) lists Louis Kaufman as the participating

violinist. Kaufman played violin in many of Korngold’s movies, but

his other claim to fame is having been the first violinist to record the

Four Seasons.

The exhibition and catalogue are presented in German and English

throughout and

runs through May 18th.

Photos of Erich and Julius Korngold © Korngold

Family Estate.

Poster of the Film

Kings Row, Warner Brothers 1942, modified

Public Domain.