Other Links

Editorial Board

- Editor - Bill Kenny

Founder - Len Mullenger

Google Site Search

SEEN

AND HEARD REVIEW ARTICLE

The Genius of

Valhalla – a celebration of Reginald Goodall:

Introduction

by Humphrey Burton and panel discussion with Norman Bailey, Margaret

Curphey, Dame Anne Evans, John Lucas, Sir Brian McMaster, Anthony

Negus and Nicholas Payne. Followed by a showing of The Quest for

Reginald Goodall a BBC TV Omnibus programme; originally

broadcast in 1984. London Coliseum, London 23.11.2008 (JPr)

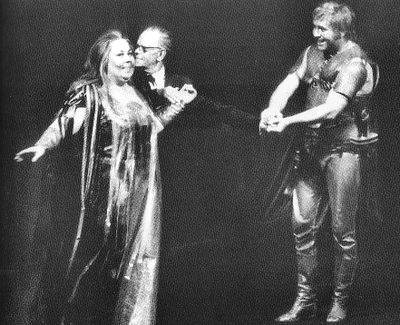

Rita Hunter, Reginald Goodall and Alberto

Remedios

Reginald Goodall was one of the most revered Wagner

conductors of the twentieth century. When he died in 1990 aged 88

he had achieved cult status but it was only during his last twenty

years that he became well known. Yet in 1945 he had conducted the

première of Benjamin Britten’s Peter Grimes when the Sadler’s

Wells Theatre reopened after the war. His performances were

considered by the first Grimes, Peter Pears, to be better than those

conducted by the composer himself.

Goodall was born in 1901 in Lincoln and studied conducting and piano

at the Royal College of Music. He travelled throughout Germany and

Austria to observe the premier conductors of the day whilst

supporting himself as a piano accompanist. His first appointment was

as choirmaster and organist at St Alban’s, Holborn, in London were

he gave a number of important first UK performances of music by

Bruckner and Britten amongst others. In the late 1930s he started

work as an assistant to Albert Coates at Covent Garden and with the

Royal Choral Society under Malcolm Sargent. The war was a miserable

time for anyone pro-German and therefore for the regrettably

pro-fascist Goodall yet within a short time of Germany surrendering,

he was surprisingly asked to conduct Peter Grimes written by

the pacifist Britten and with Pears ,another pacifist, in the title

role.

The following year in Glyndebourne’s first post-war season,

Goodall

shared the baton with Ernest Ansermet for the first performances of

The Rape of Lucretia.

Goodall

soon joined the music staff of the Royal Opera at Covent Garden and

in 1953 after replacing Britten as conductor of Peter Grimes

there - and because of the excellent reviews he received – he was

given four performance of Die Walküre on tour. The first in

Croydon on 5 March 1954 was given a glowing appreciation by a young

Andrew Porter in Opera magazine. Porter was later to

translate the Ring for Sadler’s Wells and Goodall was on the

path to becoming recognised as a Wagner specialist. However his time

at Royal Opera was to be one of relative obscurity and although he

conducted a wide repertoire from Il trovatore to Troilus

and Cressida, his opportunities became less frequent for

various reasons. He continued however to coach singers in ‘Valhalla’

- the nickname given to the small, sparsely equipped room (used by

cleaners at night for their mops and buckets and as a changing room

for front-of-house staff) under the roof of the Royal Opera House.

There, during the 1960s he coached singers such as Amy Shuard,

Otakar Kraus, Ronald Lewis, Gwyneth Jones, Donald McIntyre, Gwynne

Howell, Ronald Lewis, Michael Langdon – to name a few. He continued

to coach singers in ‘Valhalla’ even when preparing performances for

the other companies he worked with. In the opera house refurbishment

I believe this room became a toilet and so presumably not the best

place for a plaque!

He was

given few further opportunities to conduct the operas by Wagner, the

composer he most admired, but he was invited by Sadler’s Wells Opera

to conduct a new production of The Mastersingers to mark the

opera’s centenary in 1968. Those performances have become the stuff

of legend as has his Ring cycle built up between 1970 and

1973 and the first to be given in English for some years. He also

conducted Das Rheingold and Die Walküre for The Royal

Opera, Tristan und Isolde for Welsh National Opera and

Tristan and Parsifal for English National Opera, which

Sadler’s Wells Opera later morphed into becoming. He was awarded a

CBE in 1975 and knighted in 1985.

In his last years, I knew ‘Reggie’ as his friends and admirers

affectionately called him when he was president of The Wagner

Society but my most abiding memories are of a frail old man being

carried backstage in the arms of a nurse after Act I of Tristan

and Isolde at the London Coliseum in January 1985 and his being

present for an incandescent Parsifal Act 3 at the BBC Proms

on 9 August 1987. In his splendid, but sadly out-of-print,

biography Reggie – the life of Reginald Goodall, John Lucas

reminds us that this was ‘the final conducting engagement of his

career’.

‘Genius’ was

a tribute that Goodall would have abhorred as referring to himself

and what made him the genius that he undoubtedly was, is

difficult to pin down exactly. The administrator Brian McMaster

noted that Goodall was accused of having ‘no conducting technique’

yet he did have the phenomenal knack of getting a desired result

from an orchestra. Goodall’s collaborator the conductor Anthony

Negus, said he chose to ‘nurture’ the music in order to get from his

orchestras ‘a chamber music-like way of playing with a wonderful

sound’. Goodall told the singer Margaret Curphey that ‘I can’t tell

you how to sing but learn what I say’ and Norman Bailey, Goodall’s

Hans Sachs and Wotan, recalled that he was ‘wonderful playing the

piano but when he sang he had 3 pitches and it was a matter of

absorbing the music from Reggie’. Anne Evans remembered being

told to ‘Shush’ before even singing a note. When asked why,

Reggie’s reply was ‘I know it will be too loud’! Alberto Remedios

(in a message read by Humphrey Burton) made the pun that he didn’t

like to ‘regimented’ but always enjoyed his sessions with Goodall

even when Reggie came to him during the intervals of their Wagner

performances to point out that he had missed a note or phrase. He

would say, Alberto recalls, ‘Don’t worry we can go through it

tomorrow’!

There was much discussion why Goodall had not been more successful

earlier in his career particularly during his time on the music

staff for the Royal Opera. The consensus was that rehearsal time he

wanted and his other demands were too troublesome. Nicholas Payne

told how Goodall once wanted 9 double basses at Welsh National Opera

and how after he was offered 7, finally agreed a compromise of 8;

‘I had to lose the extra orchestra costs under other headings’, he

said. Nicholas Payne went on to consider how Goodall was happy to

rehearse although it was often difficult to get him to do the

performances. Brian McMaster added that once there was a midweek

Tristan und Isolde revival performance with Welsh National Opera

and unusually for Goodall evenings, it was not sold-out. The

conductor did not find this out until he came to the podium for Act

I and during the interval he refused to conduct Acts II and III.

Finally he agreed to continue for Act II but that would be all

until McMaster gathered everyone available from backstage and

front-of-house to stand and cheer Goodall as he entered for Act II.

No more was ever said and he went on to conduct Act III.

Whether or not Goodall left a ‘legacy’ was also considered and

John Lucas reminded us that because of the ‘principles of Wagnerian

technique’ that he instilled in the singers and musicians who worked

with him - and who now teach this to their students – it was clear

that he does. We were also reminded that in 1989, three of his

protégés, Anne Evans, John Tomlinson and Linda Finnie sang in the

Ring at Bayreuth. Norman Bailey summed it up best when he said

that for opera Goodall had ‘the love of the language and the

language is the soul of the music’.

Humphrey Burton then introduced his 1984 BBC TV programme The

Quest for Reginald Goodall a rare and poignant glimpse of such a

quiet and unassuming man being talked about and forced to talk about

himself, whilst more revealingly being seen working on Die

Walküre at Welsh National Opera. Overcome by these memories

Humphrey Burton abandoned a post-screening discussion saying that

this was the ‘fitting end’ to a memorable afternoon.

On 4th May 1990, the bed-ridden Goodall

told Anne Evans ‘I’d like to have one more go at the Ring,

dear. I never got bits of it right. It’s the work of a lifetime.’ As

John Lucas writes in his Goodall biography ‘That night, while

listening to Götterdämmerung, he drifted into a coma and

never came out of it.

Through

the determination of Sir Peter Moores and his Foundation Goodall’s

‘English’ Ring was ‘captured live’. These recordings and also

the BBC broadcast of The Mastersingers from 10th February

1968 are preserved on re-mastered recordings on Chandos Records’

‘Opera in English’ label. It was Peter Moores in fact who was

responsible for this splendid meander down a Wagnerian yellow brick

road. So a big ‘Thank you’ to him … and to Reggie - his dubious

personal politics forgotten if not forgiven - for some wonderful

musical memories!

Jim Pritchard

Picture © The Observer Newspaper

Recording Details:

THE

MASTERSINGERS

- CHAN 3148

THE

RING OF THE NIBELUNGS

The Rhinegold

– CHAN 3054

The

Valkyrie

– CHAN 3038

Siegfried

– CHAN 3045

Twilight of the Gods

– CHAN 3060

Back

to Top

Cumulative Index Page