S & H Opera Review

Thomas Adès, The Tempest, based on the play by William Shakespeare. World Première, The Royal Opera House, Covent Garden: soloists, Royal Opera House Orchestra, conducted by the composer, Tuesday February 10th 2004. (ME)

‘Be not afear’d; the isle is full of noises / Sounds and sweet airs, that give delight, and hurt not’ as Ian Bostridge’s Caliban does not inform us in Adès’ new opera: that of course was Shakespeare, Bostridge being given the dubious delight of singing instead ‘Friends don’t fear / The island’s full of noises / Sounds and voices / It’s the spirits.’ Well, at least he fares better than Simon Keenlyside’s Prospero, vowing ‘I’ll break my stave / I’ll rule in Milan / Beside my grave’ (Eh?) or indeed, just to pick at random, ‘Sorcerer, die. / Caliban, why?’ and Miranda’s ‘Father don’t oh father please / Try to put him at his ease.’ Oh, stop it, I hear you say – if we want dialogue of the quality of ‘Footballers’ Wives,’ we can watch it tomorrow night, complete with lines like ‘You’ve got to be strong.’

‘Primo le Parole, doppo la Musica?’ Well, of course not: music and language are ideally indivisible, but what is the relation of doggerel such as the libretto of this work, to the great original play, and to the music itself? This question has a special relevance as far as Shakespeare’s Tempest is concerned, since that play, more than any other, is suffused with music – not just in terms of the famous songs such as ‘Full fathom Five,’ but the language used to depict the music of the Island, and the music of the cadences of the pentameters themselves. In the programme notes we are informed that ‘In realizing the ambiguities of The Tempest, Adès releases music’s magical power.’ I’m not entirely sure whether or not there’s some confusion here between the verbs ‘realize’ and ‘release’ or indeed whether or not this qualifies as arrant, or merely arrogant, nonsense, but nonsense it is – whatever is meant by the ‘magical power’ of music, it hardly needs Adès to release it from Shakespeare’s play, which breathes it from every phrase, and as for ‘realizing the ambiguities’ of the play, I’m not sure if they need ‘realizing’ since it is the lack of realization which makes any ambiguity what it is. All this stuff might well apply to the piano music of Janácek (on which Adès original comment was based) but it has little or nothing to do with Shakespeare.

It’s all very well to say that the opera is ‘based’ on Shakespeare, or that the libretto is ‘an interpretation’ or that ‘all operas adapt their originals’ – they do, but what glory Verdi, Piave and Boito created when they ‘adapted’ Shakespeare, and what a travesty has been offered to us here. Is the music as bad as the libretto? Fortunately, no, but it’s merely pleasant stuff at best, heavily indebted to Britten, Strauss and Tippett amongst others – although would that Adès had the last composer’s skill in evoking the ethereal as evidenced in the ‘Songs for Ariel.’ Perhaps the best music is in the semi-duets for the ‘young’ lovers and the extended passage for Caliban, but even then it’s merely agreeable. The opening of Shakespeare’s play is one of the most immediately gripping in the canon, but here the tempest is rather weakly evoked, as is the suggestion of individual musical character for each protagonist. Prospero is envisaged as a creating his illusions on a magical palimpsest, tetchily reflecting on his lot as he does so, declaiming his grouchy feelings with gusto but never really possessing that sense of power which Shakespeare’s ‘sorcerer’ has – of course, Prospero is a version of the Creative Artist, renouncing his power over the audience at the play’s end, but there was little sense of that here.

The concept of Ariel as a high-lying coloratura soprano makes obvious sense in that the character is other-worldly, but her music is too often a series of yelps in high E – fair enough, characters like Zerbinetta and Fiakermilli are pitched nearly as high, but the music still retains its line, which was not the case here. For Shakespeare’s monster, with all his complexities of a beast wanting discourse of reason combined with his startling sensitivities to beauty in all its guises, we had a high lyric tenor – perverse, to say the least, since most of Caliban’s fascination surely lies in his nature as what Prospero calls a ‘thing of darkness’ – hardly the frilly, jokily becrowned mimsy being presented here. Other parts were more suitably cast, especially in the cases of Stephano and Gonzalo.

As has been repeatedly written in all the pre-performance hype, the cast is composed of a ‘Brit Pack’ of the highest musical excellence, with a couple of guests from across the pond. Certainly, the cast make up some 90% of the best of current British singers, and Adès was fortunate indeed that such highly cultivated distinction was laid on for him, but one did find oneself wishing that they had been given music to match their quality. Keenlyside did all he could to make this arid, hectoring Prospero a humane figure, singing with his customary beauty of tone and rarefied timbre, and Bostridge provided the evening’s best moment in his ‘aria’ which was sung with exact diction and wonderful projection – what a pity his character was so loosely defined, both musically and dramatically. Cyndia Sieden sang with plenty of confidence as Ariel, although the concept of her character as presented here tended to deprive her of that essential element of sympathy at ‘Mine would, were I human.’

Ferdinand and Miranda were affectionately taken by Toby Spence and Christine Rice, both producing warmly phrased, sweetly sung lines although the latter was a touch matronly for the teenage innocent whose wide-eyed ‘O brave new world’ defines her place in the scheme of things. All the minor parts were cast from strength, especially in the case of Philip Langridge’s King of Naples: no matter what drivel he was forced to sing (Gonzalo heed me / You’ll succeed me / I’ll see to it / You will be regent) that incisive tone, that unique quality of pathos in the phrasing came through in every line – how consoling to see and hear him in such fine voice after the horrible mistake of his Glyndebourne Idomeneo. Gwynne Howell’s Gonzalo (yes, one of the smallest parts was sung by the Pogner of our time) was a tower of strength, Lawrence Zazzo’s Trinculo made his mark despite music which tended to dissolve his lines, Stephen Richardson sang Stefano with plenty of bite even though his role was subdued, John Daszak was an entirely credible Antonio and Christopher Maltman distinguished himself as a bullish Sebastian, making complete sense of his words despite their awkwardness.

The production (Tom Cairns, with lighting by Wolfgang Göbbel) was like the music – not really up to much despite all the huge hype and vast resources lavished upon it. The opening scene’s choreography, of an ‘Ariel dancer’ gracefully tumbling over and over at almost full stage height would probably have seemed strikingly original to anyone who had not seen exactly the same thing done by Trisha Brown’s figure of Musica in the Brussels production of ‘L’Orfeo,’ and in the same way anyone not familiar with the David Pountney ENO production of ‘The Cunning Little Vixen’ would probably be enthralled with the insect movements later given to Ariel. The set seemed to be conceived as a kind of huge palimpsest for Prospero’s own stagings for the lives of the characters, brightly lit and jazzily stabbed with evocative laser work – taken on this sort of quasi-abstract level it is attractive and vibrant, with lots to engage the eye such as cuddly monsters who seem to have strayed from a student production of ‘Die Zauberflöte’ but none of it really ‘gels’ – no tempest as such, no real sense of the Island as a place of magic import.

No doubt the newspaper reviewers will all have come to the conclusion that this work is a coruscating masterpiece, but someone has to say that the emperor, whilst not exactly naked, is not robed in the magnificence with which he will surely be regaled. An evening of mostly wonderful singing, attractive but hardly enthralling production and music which seldom rose above the agreeable. Shakespeare’s ‘heavenly music’ hardly requires such addition:

And like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud – capp’d tow’rs, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve,

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep. (The Tempest, Act V)

Melanie Eskenazi

Photo Credits:

Ferdinand - Toby Spence

Ariel - Cyndia Sieden

Photo Credit: CLIVE BARDA

Prospero - Simon Keenlyside

King of Naples - Philip Langridge (left)

Photo Credit: CLIVE BARDA

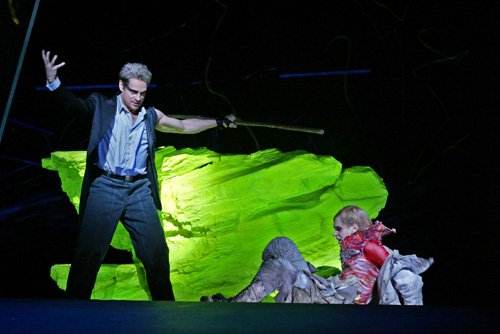

Prospero - Simon Keenlyside

Caliban - Ian Bostridge (rt)

Photo Credit: CLIVE BARDA

Prospero - Simon Keenlyside

Ariel - Cyndia Sieden

Photo Credit: CLIVE BARDA

Return to:

Return to: