S & H Concert Review

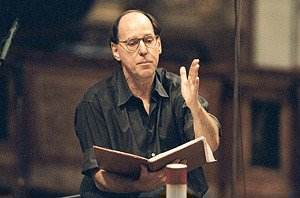

Mahler, Symphony No.2, Inger Dam-Jensen (sop), Nadja Michael (mezzo), London Philharmonic Choir, Brighton Festival Chorus, Philharmonia Orchestra, Gilbert Kaplan, RFH, 4th November, 2003 (MB)

"One is battered to the ground and then raised on angels’ wings to the highest heights," Mahler wrote after hearing his Resurrection Symphony for the first time. And in many ways this was exactly the kind of performance Gilbert Kaplan gave us on Tuesday evening. This was a performance that was often shattering, with some of the widest dynamic extremes I have ever encountered in this work. Whether it was the way Mr Kaplan succeeded in getting the Philharmonia strings to hum like birds at Fig.5, with breathtaking clarity given to the pp – ppp marking, or the fff opening of the fifth movement which was given unusual terror, Mr Kaplan’s fidelity to the score was absolutely convincing.It was certainly an uncommonly good performance, dramatically and starkly conceived as a single arc in its expressive range. And although this was not a first performance of the new critical edition of the score (due to be published at the end of 2004) nor was it simply Mahler as we are used to hearing it. Mr Kaplan had spent some time correcting parts in the Philharmonia’s scores but it sounded very far from being a mere hybrid. Part of Mr Kaplan’s genius is that any performance he does of this symphony just sounds so different, so fresh. In the coda of the first movement, for example, the inflexibility of Mr Kaplan’s initial tempi, so implacable, was a welcome contrast to the three pizzicato chords which close the movement, the balance between mf and pp achieved with striking clarity and with equidistant rest marks observed. It is not often played like this – and certainly not in the four other performances of the symphony I have heard in concert this year. In the Ländler he achieved a remarkable sense of Viennese grace without quite diminishing the movement’s bucolic moments. It might not have been so effortlessly played as this movement is on his new recording of the work but the Philharmonia strings were buoyant and lilting with a range of expression only this London orchestra seems capable of displaying at the moment (and as if this needs to be illustrated further listen to how they achieved such perfectly played glissandi in the first movement at Fig.23).

The third was incisive – pinching timpani, noble brass – with Mr Kaplan fully aware of the movement’s sardonic implications. And as they were to be in the final movement, climaxes were crushing. At Fig.50, for example, with strings crying out at ff he developed a measured crescendo that built up to a massive fff in the brass and woodwind that imploded with apocalyptic force. Yet, the coda – with a beautiful diminuendo on first violins, and a gorgeously articulated pppp in the ‘cellos that almost seemed frayed at the edges, so angelically was it played – was magical. Nadja Michael’s hushed opening to the Urlicht section was perhaps slightly heavy with vibrato, but she brought with it a plushness of tone that proved to be a turning point in the performance, an object lesson in how Mr Kaplan would treat the voices in this symphony, which would be given the same clarity of phrasing as he had given to the orchestration.

And the gigantic final movement was a combination of awesome violence and almost reverential spirituality (although, admittedly, Mr Kaplan’s rather than Mahler’s). After the explosive opening bars (more profoundly gripping than usual), at Fig.8 Mr Kaplan shifted gear with the sense of mounting terror given cumulative, tsunamic force. But even amidst this tumult he was able to sustain the impression of hidden beauties in the orchestration. Quite possibly the most extraordinary (and certainly most memorable) playing of the entire performance came at Fig.10 where four trombones and a tuba intone at pp for a glorious 8 bars. Not only was the playing of the Philharmonia brass peerless it was also intensely moving with each instrument not only a singular voice but a unified one that pre-empted the beginning of the Klopstock resurrection theme in the chorus.

The choral singing itself had tremendous clarity and reached its apotheosis in the movement’s crowning passage which swelled dramatically, their last syllable gloriously taken over by chiming bells. Yet, oddly, for all its impressive range, the singing didn’t quite move in the way it should. But the ending – with 11 horns now on stage – was as satisfying as any I have ever heard, an impressive testimony to both Mr Kaplan’s conducting and the Philharmonia Orchestra’s belief in his approach to this masterpiece.

Throughout, the Philharmonia’s playing was magnificent. If the strings did not quite achieve the sonorous depths that the Wiener Philharmoniker do on Mr Kaplan’s new recording (reviewed below) they made up for this with playing of superb range; there were some literally transcendent pianissimos (especially from the ‘cellos). On stage brass – notably the superb horns and trombones – were impressive, with only the slightest hint of tonal problems occurring in the off stage brass band in the final movement. But this was Mr Kaplan’s triumph and a capacity audience clearly felt so too.

Marc Bridle

Gilbert Kaplan talks to Marc Bridle about Mahler’s Second Symphony.

Colin Clarke reviews Gilbert Kaplan’s new recording of Mahler’s Second Symphony below:

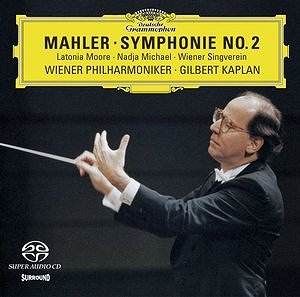

Mahler, Symphony No. 2 in C minor, ‘Resurrection’, Latonia Moore (soprano); Nadja Michael (mezzo); Singverein der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde; Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra/Gilbert Kaplan.

DG 474 380-2 [DDD] [85’48] Rec. Vienna, Musikverein Nov & Dec 2002.

Gilbert Kaplan’s obsession with Mahler’s ‘Resurrection’ Symphony has led him to Vienna. Here are his most recent thoughts on a score in which he has located over 400 received errors in a performance that uses the critical edition published jointly by Universal Edition and the Kaplan Foundation. Most of these corrections will not be immediately aurally obvious on hearing these discs, but what will be is Kaplan’s tremendous and intimate knowledge of the score. Minutiae are worshiped and the recording quality aids and abets this. Crystal clear, and revealing the Vienna orchestra truthfully, this superior sound means that right from the beginning doublings are aurally obvious.The Vienna Philharmonic is in tremendous form, backing Kaplan’s conception to the hilt. Singing, aching string lines contribute to the ‘rightness’ this first movement exudes. Only a couple of points raise question marks. The orchestral ‘crashes’ at 11’59 that interrupt a restatement of the opening gestures could certainly be more visceral; without recourse to a transcript of Kaplan’s scholarship it is likewise difficult to tell whether the Luftpausen at around 14’24 ff are imperfectly realised or whether the effect is purposeful. There certainly seems to be some editing here, as there is a subtle acoustic change. The standard of playing is superb, of that there is no doubt and the level of detail to be heard is a model, the clear recording being part and parcel of this. Despite all this (possibly because of it), this is not a movement of awe-inspiring grandeur of conception and maybe that is Kaplan’s Achilles heel. He is still on a journey to find his ‘perfect’ realisation, it would appear, and so this is actually historical musicology in progress (albeit with the greatest vehicle in the world to practice it on).

There is a literalism present in the second movement that lends the music a certain dignity but robs it of any suave leanings. The third movement avoids any such trap. Quixotic and elusive, Kaplan here takes us into a shadowy world where bass-lines creep menacingly. Unfortunately the horn ‘whoops’ (notated whoops, though) are calculated in their execution, not nightmarish shrieks.

So to the first of the soloists. Nadja Michael is the tremulous mezzo in ‘Urlicht’, far too much so and it is especially distracting given Kaplan’s funereal pace. It becomes in the light of this difficult to resonate with the underlying meanings of Mahler’s chosen text (from ‘Des Knaben Wunderhorn’).

An over-careful approach is again in evidence at the very opening of the final movement. True, one can hear absolutely everything, but it sounds calculated. A pity the movement starts like this, for it continues very well. Brass chorales are beautifully warm; ‘Dies irae’ repetitions are remarkably ominous; off-stage brass is miraculously balanced in the stereo picture. Yet the downside of the recording is that some typically DG close-miking can really throw the listener off-balance (be warned, flutes will whizz at you).

The segue between the dying flute arabesques and the choral entry (‘Aufersteh’n’) is strange. There is no pause between the two, no space to let the atmosphere resonate. The chorus is excellent, though. A pity Kaplan makes Mahler’s orchestral doublings of the chorus so obvious, as surely they are there to keep less-than-top-flight choruses in tune. They do sound clumsy, it has to be admitted. The final affirmation of ‘Aufersteh’n’ is not truly climactic, a necessary consequence, possibly, of Kaplan’s approach, but hardly an apt reaction to Mahler’s fervent religiosity. This is not the affirmation it should be.

It would be interesting to clarify the markings on the ‘sfp’s close to the end of the work: are they marked ‘sffp’, then a ‘mfp’? Bernstein was one to make a huge deal out of these (memorably), here they just sound literal.

There is much to admire in this reading and the VPO is a delight from first to last, but ultimately this ‘Resurrection’ does not emerge as the life-enhancing affirmation it can be.

An artist discussion with Kaplan is planned on the DG website for November 24th, 2003. Questions can be posted between November 13th-21st. The Kaplan Second is also available on SACD (474 594-2).

Colin Clarke

Gilbert Kaplan talks to Marc Bridle about Mahler’s Second Symphony.

Return to:

Return to: