S & H Opera Review

Richard Strauss, Elektra, ROH, Covent Garden, 4th April 2003 (MB)

This is perhaps as much Charles Edwards’ Elektra as it is Richard Strauss’. He direct as well as designs both sets and lighting for this new production, and if he doesn’t entirely succeed in dispelling the memory of Götz Friedrich’s 1997 Elektra at Covent Garden (with more visually striking sets by Hans Schavernoch) it isn’t nearly as bad as some early reviews have suggested. Urban and psychological decay are as much a part of the twentieth century as it was of Sophoclean Greece, perhaps more so, and Edwards’ sets are scrupulous for the detail he sheds on the rotting corpse that has become the House of Atreus.

In truth, Edwards brings elements of both eras to this production. The upward slope of the staging almost suggests an archaeological excavation: the wreck of Agamemnon’s Atrean household, with his desk sliding into oblivion and his papers strewn across the stage, always seems to be teetering on the brink of further collapse, held together only by the conviction of Elektra’s own belief in revenge. But so too does the Palladian grandeur of Klytemnestra’s household looking more like the decaying front of a Mussolinian hotel, with its windows opaque with dust and revolving doors offering us but a kaleidoscopic glimpse of life inside her court.

This is an Elektra who cannot escape the ghost of her murdered father. Along with the severed head of Agamemnon, stonily staring outwards like that of Medusa, his shadow looms larger than life over this production. During her great opening monologue his shadow appears against the stone wall building in ever greater intensity until it fades like parchment (‘Ich will dich sehn, laß mich heute nicht allein!/ Nur so wie gestern, wie ein Schatten dort/ im Mauerwinkel zeig dich deinem Kind!). It is all much starker, and more prominent, than the suggested activity from within the walls of Klytemnestra’s house which remains largely half-hidden – only to be brought into shocking distillation with her own murder at the hands of Orest shown as a silhouette of striking vividness.There are drawbacks to this design, however. Klytemnestra’s procession, for example, so rampant and majestic in Friedrich’s production is here all but shrouded from view, with only the briefest glimpse of light, and only a suggestion of commotion. But whilst Klytemnestra’s own arrival on stage is without the fanfare it had in Friedrich’s staging it does make Klytemnestra more the focus of action than it did in the earlier production. Such frequent use of the revolving doors makes some of the action appear congested – Aegisth’s murder seems unduly over-dramatic as he spins round and round, and Chrysothemis’ final appearance on stage, almost jammed into the doors, is unconvincing, especially since so much of the action is then concentrated on looking at the corpses littered across the stage and the house burning in Götterdämmerung-type oblivion.

So much for the staging, what about the singing? One constant between this production and the 1997 Elektra is the casting of Felicity Palmer as Klytemnestra. Dramatically, she dominates Edwards’ production bringing vividly to stage the cruelty, dementia and hysteria of Klytemnestra. It is a tour de force of acting and stamina, although I am less convinced by her vocal strengths. As with the role of Elektra, Strauss cruelly exposes Klytemnestra’s vocal writing in the upper and lower registers. Ms Palmer is quite magnificent in the lower and middle reaches, indeed I would be hard pressed to think of a more convincingly sung nightmare than what we had here with the tension she produced in her voice proving not just haunted but genuinely paranoiac. When Elektra interprets her dream of the anonymous terror as the avenging Orestes Ms Palmer visibly looks on the point of collapse, ‘Mutter, du zitterst ja!’ Elektra exclaims. However, whilst the voice above the stave is secure it is often an uningratiating sound, although even that can be forgiven in a portrait that is really one of the monstrous creations of our time. How she caresses her jewels and lurches like a female hunchback across the stage suggests real understanding of Klytemnestra’s emotional chemistry. And if vocally there were moments of discomfort lines like ‘Und müßt ich jedes Tier, das kriecht und fliegt…’ were delivered with the kind of fortitude and rasping hatred which makes her one of the outstanding interpreters of the role today.Anne Schwanewilms, as a ravishing Chrysothemis, is thrilling, if a little too plain in her delivery. Utterly believable on stage, her voice is of rare beauty and a natural foil for the more earthen Elektra of Lisa Gasteen. Siegfried Jerusalem is a bumbling Aegisth, but with those honeyed-tones a consistently lyrical one, which is not always the case. And such impeccable diction came as a relief after the LSO’s recent Salome where it was sorely lacking. John Tomlinson, making his role debut as Orest, is richly dramatic, his shock in finding Elektra degraded by Klytemnestra’s cruelty genuinely affecting in its warmth and humanity. However, like Elektra he spends a great deal of his time immobile but the presence of a great actor on stage is undeniable.

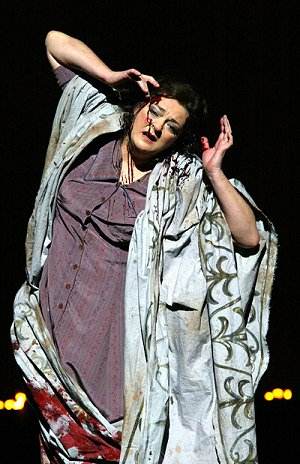

Lisa Gasteen’s Elektra will not be to everyone’s taste. Dramatically, her performance is weak, although how much this has to do with the minimal stage direction is as debatable as the fact that the staging itself reduces the ability of the singer to really make much (dramatically) of the innate rage for vengeance which dominates the psychology of the role. This has certainly never been a problem with her Wagner, but here she was a slight disappointment. Memories of Deborah Polaski’s ‘warrior’ Elektra are certainly not dismissed by Ms Gasteen’s rather mouse-like portrayal of Agamemnon’s daughter, the former a feisty, heroic daughter (surely as Agamemnon would have remembered her) the latter a house-frau content to fester waist high in her pit at the base of her father’s crumbling desk. The fact that Ms Polaski had been garbed in a vast trench coat and Ms Gasteen in little more than a drab maid’s dress highlights how directors differ in their view of this complex character. Which you prefer will surely be a matter of personal taste.

Yet, no matter how deficient Ms Gasteen maybe with matters of drama there is little doubt that vocally she can meet the challenges of Strauss’ score. The voice settled as the opera unfolded, her opening monologue having been a little too introspectively delivered, but during, and after, her scene with Klytemnestra she found the right balance between taunting her mother, believing she is victorious, and falling into despair when she is told that Orestes is dead. If, dramatically, the changing focus of Klytemnestra’s mood, from a feverish wreck to a triumphant tormentor, had been conveyed majestically by Ms Palmer’s acting, then it was Ms Gasteen’s triumph that the voice did the acting for her. The sheer difference in her tone colour, and delivery, between ‘Träumst du. Mutter?’ and ‘Was sagen sie ihr denn?/sie freut sich ja!’ was a minor miracle of musical artistry.

The opera’s lyrical highpoint – the Recognition Scene – brought intense beauty of tone from both Ms Gasteen and Mr Tomlinson, but she kept in store sufficient reserves for her final scene, which again, if very one dimensionally acted (no dance whatsoever, in fact), was superbly sung and articulated. This is by no means a complete characterisation of Elektra but it has the promise to be a great one, especially vocally, and at the moment the voice is convincing throughout the register, and notably beautiful in the middle where so much of Elektra’s lyricism is reserved.

Semyon Bychkov, replacing Christoph von Dohnanyi, doesn’t always strike me as an innate Straussian, as the latter very obviously is (his magnificent Salome at Covent Garden being a prime example). Occasionally, climaxes seemed very slightly undernourished – the opening bitonal chords and Klytemnestra’s procession weren’t quite fiery enough, for example – but his view of the score is a gripping one. This was especially the case with the opera’s closing chords which were riven with pile-driven angst. He persuaded the orchestra to play with precision and beauty, lingering lovingly over Strauss’ lyrical phrases during the Recognition Scene and giving brute force to moments such as Klytemnestra’s murder which, with her own shrill screams, was a moment of blood-curdling terror. Indeed, the playing was never less than magnificent, utterly transparent and perhaps the one unquestionable success of this production. One would have to go very far to find a better played account.

This production of Elektra is not everything it might have been, but it rarely disappoints. And as a reminder of how great Strauss’ opera is it makes for an arresting evening.

Marc Bridle

PHOTO CREDIT: CLIVE BARDA

Elektra - R Strauss

ROH 27.3.03 (new production)

Orestes - John Tomlinson

Aegisthus Siegfried Jerusalem

Elektra Lisa Gasteen

Conductor - Semyon Bychkov

Production and set designs - Charles Edwards

Costume designs - Brigitte Reiffenstuel

Movement - Leah Hausman

Return to:

Return to: