S & H Recital Review

Dvorak, Read Thomas, Bartok, Ilya Gringolts (vln), Boris Berezovsky (pf), Wigmore Hall, 17th March 2003 (MB)

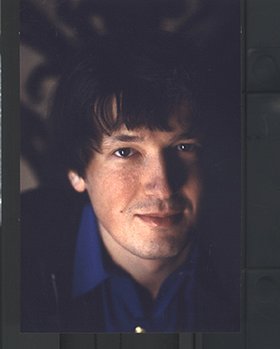

Ilya Gringolts already has a far-reaching international reputation so he is hardly a discovery in the sense that one of the BBC’s New Generation Artists from last year, Simon Trpecski, was. A recent disc of Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich violin concertos for DG (but hardly a front runner) shows Gringolts to have the necessary virtuosity for a top-flight player, but it concerns this reviewer that he brings such repressed artistry to his concerts and discs.

This concert started in much the same vein as his previous Wigmore Hall recital – depressingly. Dvorak’s Four Romantic Pieces - ‘romantic’ – displayed Gringolts’ characteristically clean articulation, but the interpretations of these mellifluous and lyrical miniatures were delivered one dimensionally, even blandly. Although dynamics were impressively contoured (with some beautifully hushed pianissimo playing in the Larghetto) Gringolts didn’t deploy widely enough a sufficiently colourful tonal palate. Too often his sound lacked warmth, in part because he tended to reduce his vibrato to a minimum. The very close of the work was, for example, unevenly expressive – almost dismissive of Dvorak’s elegiac, troubled sound world. Much better was his accompanist, Boris Berezovsky, although even he had problems toning down his piano sufficiently – at times allowing himself to drown out the violin almost completely.

Augusta Read Thomas’ Pulsar, written for Ilya Gringolts and, in a world premiere performance, is a minor addition to the solo violin repertoire. In sheer scale it lacks the drama of Bartok’s own ‘Solo Violin Sonata’, and in sheer inventiveness it lacks anything that Bach brought to his six major pieces for the instrument. Lasting for about ten minutes, it is designed as a triptych – conservatively composed in a slow-fast-slow form. Ironically, its icy opening glissandi on the E string suits Gringolt’s natural harshness of tone and its frequent double stopping and high-ridged harmonic tonality works well with his austere deployment of dynamics. Long and short bow lengths, often within the same bar, give the work a very uneven feel to it, although in the middle section the low G string sonorities brought forth some of that warmth of tone so conspicuously missing from Gringolt’s performance of the Dvorak.

Bartok’s great Sonata No 1 took up almost half of this recital and the performance was astonishing; in fact, everything previously lacking in Gringolt’s earlier performances was here miraculously restored. Partly because there is virtually no thematic material throughout the entire course of the sonata that is shared between the piano and the violin, performances of this work can achieve levels of improvisatory inventiveness rarely encountered in other violin sonatas. Berezovsky and Gringolts certainly seemed destined for a clash of titanic proportions – with each firing off volleys of sound incandescently. During the long allegro Berezovsky often swamped his partner, but Gringolts brought a nerve-shredding virtuosity to his playing that, as cleanly articulated as it was here, proved thrilling. The adagio brought that hitherto missing warmth of tone from Gringolts – indeed, the lyricism was often spellbinding, even more so when he was able to measure his fastidiously prepared double-stopping with such acute dynamic sensitivity. The final movement allegro was simply exhilarating, especially the coda which exploded in splinters of virtuosity. Quite wonderful playing from both musicians made this performance at least unforgettable.

Marc Bridle

This concert is repeated on BBC Radio 3 on 23rd March 2003 at 1pm.

Return to:

Return to: