S & H International Ballet Review

Propoganda, parody, or paean?

Alexei Ratmansky choreographs the first revival of Shostakovich’s

1931 "socialist ballet" rarity in 70 years at the Bolshoi.

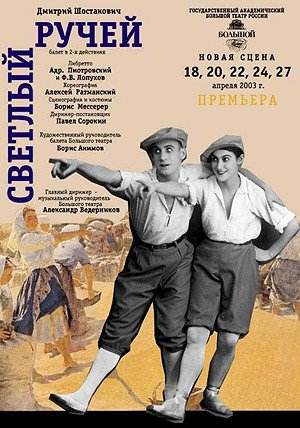

Svetly Ruchey ("The Bright Stream"), Dmitri Shostakovich,

The Bolshoi Theatre (New Stage), Moscow,18th April 2003 (NMcG)

Anyone who’s read-around the topic of "Music & Politics" will almost certainly have come across the clash of ideology between soviet composer Dmitri Shostakovich, and soviet leader Joseph Stalin. Matters between composer and leader came to a head over Shostakovich’s second opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtensk – famously described as "Muddle instead of Music!" in a Pravda editorial believed to have been penned anonymously by Stalin himself. The plot of Lady Macbeth (which is only related to Shakespeare’s play in the vaguest details, and is based on the novel by pre-Revolutionary Russian author Nikolai Leskov – and features graphic and gruesome murders, shameless adultery, and contempt for the forces of law and order. Shostakovich’s stage version almost trumpets the aspects most likely to anger contemporary society – with on-stage attempted gang-rape, a graphic sex scene with orgasmic spurts of energy… and just as a final two-finger gesture to the censors, a closing scene in a soviet gulag. Lady Macbeth is widely performed these days, and it is easy for us to shout "philistines!" at the soviet censors… although it is a moot point whether the Lord Chamberlain’s Office would have granted it a Stage Licence if the composer had instead been Tippett or Britten?This is all very well – the Soviet Union in the 1930’s was hardly a garden of creativity, and Shostakovich can hardly have expected his Lady to have had an easy ride – a singing conga-line of incompetent cops was unlikely to get backing in the corridors of power.

But what on earth motivated the censors to close-down and ban Shostakovich’s 1931 ballet Svetly Ruchey, "The Bright Stream", a year after banning Lady Macbeth in 1935? By contrast with Lady Macbeth, the plot appears to be the ultimate in brown-nosed sycophancy towards the ideals of "socialist realism"… In the Kuban region of Russia’s South, some ballet performers from "the big city" are sent to help-out with the harvest. The workers of "The Bright Stream" Collective Farm receive their guests in different ways – many are enthusiastic and welcoming, but others are apprehensive, envious or openly hostile. In one of those coincidences which are the stock-in-trade of musical theatre, one of the local girls has secretly studied ballet when she lived in the big city herself – but has thrown it all up to marry her Agronomist husband. His open flirting with the troupe’s ballerina is hurtful to her – but the ballerina is not only an ally, but her former fellow student from Ballet School. More hostile to the newcomers are the older pair of dacha-dwellers – a miserable and curmudgeonly couple. The Ballerina hatches a plan – which owes more than a nod to Die Fledermaus – to teach everyone a lesson. The Leading Man will dress up as a ballerina – and seduce the old woman, whilst Zina will dress as a boy, and seduce the old man. The result is somewhat unbalanced – the first half is somewhat slow-moving, whereas the second half’s slapstick seductions are pure light-hearted fun. All ends happily of course – and joy is unconfined.

It’s hard to remember that the music is by the same composer as Lady Macbeth – which had premiered a year earlier. The score is a light pot-pourri of waltzes, minuets, trots, gallops, mazurkas and polkas, unashamedly written four-square, and excellently danceable. Although there is not enough musical interest in the numbers for the concert-hall, they are far from banal, and rich and varied textures propel the musical interest forwards. In a country in which relatives of "Enemies Of The State" could be jailed merely for being relatives, it seems likely that his harmless and cheerful work was merely "guilty by association" with Ekaterina Ismailova, the heroine of Lady Macbeth – it’s hardly credible that any other reason might have existed to have it banned in 1936?

How on earth to stage this period piece of agit-prop theatre? Alexei Ratmansky is the enfant terrible of contemporary Russian ballet choreography, and was called-back especially to the Bolshoi from his work at the Royal Danish Ballet to stage the piece. The original choreography had, in any case, been wholly lost, so Ratmansky took the chance to revitalise it – and what was unveiled as this season’s premier was anything but a museum-piece. The curtain rises on a fly-out banner with a massive Hammer & Sickle at its centre… but arranged around this, in the style of Soviet Propoganda, are anti-Shostakovich quotations, such as "Muddle Instead of Music!". When this too flies out, the scene opens on a massively over-the-top riot of pseudo-socialist splendour – banners, columns, pillars and sheaves of golden wheat, cheerfully expropriating the empty clichés of Socialism. Is it send-up? Is it golden nostalgia? Is it affectionate homage? Or is it all three? Ratmansky carefully leaves the jury out on the matter, which is his brilliant success – you can find any interpretation you care to in this production. What there is not, however, is the formulaic tedium of classical ballet – despite every single step being classical ballet. Ratmansky draws from every source for his ideas – ideas from "big-budget" musicals rub shoulders with pastiche Eisenstein marches. This is dancing to die for – a feast for the eyes, as well as the ears. Intense rehearsals (and rumours of complaints about being "worked too hard" for this complex production) paid-off in spades for the Bolshoi, where rapturous applause has been heard all too rarely for many seasons. They have, at last, had an unambiguous success on their hands.

Pavel Sorokin was at the helm in the pit. Perhaps the needs of ballet dancers for rhythmic playing are different, but the effervescent energy on-stage somehow failed to inspire playing of a similar kind – tired-sounding brass and lacklustre woodwind didn’t quite find the spark needed. There was a horrible feeling that this was being played with tub-thumping ideological seriousness, rather than with the playful ambiguity apparent on stage. Dmitry Miller delivered a swooning and extended ‘cello solo with aplomb, as the musical highlight of the evening.

Sergey Filin won the audience’s hearts as the Leading Man – with a loving pastiche of La Sylphide. They say that playing comedy is the hardest thing of all – and Filin’s dancing of the female role brought the house down. The stunning technique required to do this – including dancing on-point, which men "never do" – was savoured by a loving audience. In the other roles, Inna Petrova excelled as a plucky Zina, Yuri Kletsov was a dashing Pyotr, and Andrey Melanin and Lyubov Fillipova made much of their character roles as the old dacha-dwellers.

After a period in which soviet works had been excised from the Bolshoi’s repertoire in pursuit of bums on seats, it’s especially rewarding to see a forgotten Shostakovich ballet revived to such a warm reception. Let’s hope that Ratmansky is a more frequent visitor to his homeland in future….

Neil McGowan

Return to:

Return to: