S & H International Opera Review

The grotesque illusion of normality

Berg, Lulu (performed in German), The Helikon Opera, Moscow, April

19th, 2003 (NMcG)

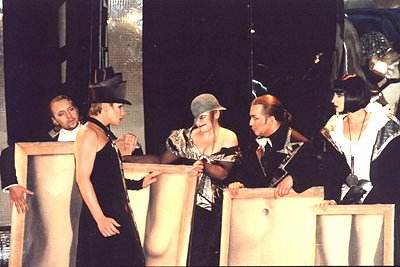

Mirrors, reflections, and imagined images are the themes of Dmitri Bertmann’s revival of his 2002 production of Lulu at the Helikon Opera. Each of Lulu’s multiple paramours sees in her not what she is – a capricious but innocent pleasure-seeking girl, guilty only of enjoying seductions and sex – but what they wish to see in her, and make out of her. Reinforcing this, a stunning set by Igor Nezhny and Tatiana Tulubieva comprises giant distorted mirrors on rolling trucks. Lulu is dressed not as a courtesan or seductress – but as a normal and attractive girl in a peach-coloured dress. The dysfunctionality of her suitors is apparent in their costumes – Dr Schoen has shoes which point backwards, and a hunchback; the Artist wears his palette as a jacket; Alva has grotesquely large "Kenny Everett" hands; the Schoolboy has monkey-ears; whilst Countess Geschwitz wears unfeasibly ankle-length kipper ties. Hold a mirror up to nature, Bertmann says, and you’ll find it is us – the editor, the artist, the young lover, the student – who are nature’s freaks, and compulsive-lover Lulu who is the "norm". Each of us acts from selfish self-interest – only Lulu can be unstintingly generous in her love to all. Watching without comment is a semi-chorus of extra-terrestrials with noses like vacuum-cleaner hoses.This latter idea seems initially preposterous, but if we take the composer’s intentions seriously – that human life is a kind of freak-show in which people behave as animals, as stated in the Prologue – then these bizarre observers establish the freak-show nature of the action of the opera itself. When the final bars ended, the audience was left emotionally stunned by the ghastly scenes they had witnessed – who did not recognise a part of themselves in what had taken place on stage? No-one, evidently, was sufficiently without fault to cast the first stone - and the cathartic experience of an expressway ride to hell’s moral depths finally elicited broad cheers and devoted applause from even the initially uncertain. Except those who walked-out – of whom there were several, including my neighbours. As the scenes tick-by, C19th lithographs – a favourite Bertmann obsession – of a naked Lulu appear frame-by-frame – first the feet, then the legs, then the crotch, and upwards, like some pornographic Advent Calendar. Her murder is achieved by Jack the Ripper sending these frames spinning with deft knife-blows…although Geschwitz catches the blade full-force. The girl whose image all sought to make their own is murdered in image only.

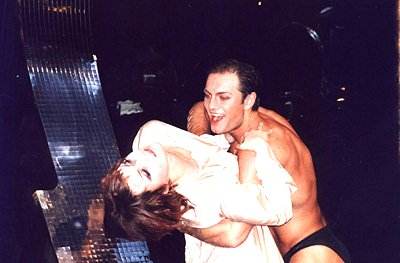

Tatiana Kuinji is a descendant of the famous Russian "light-and-shade" master-painter, whose works hang in all of Russia’s art-galleries – most appropriately, since the gradation of tone-quality and expression is one of the highlights of her spectacular talent in the title role. Her tiny frame (she is under 5’ tall) coped admirably with a highly physical production that required her to sing lying-down, facing stage rear, underneath the scenery, and hanging upside down. It’s a performance which saw her nominated for an award she’s already won on previous occasions, the Golden Mask awards – Russia’s equivalent of the BAFTAs. With no disrespect to the other cast (everything at Helikon is double-cast) of Lulu, it’s hard to imagine who might give a better, holistic, musically precise and complete performance of this taxing role?

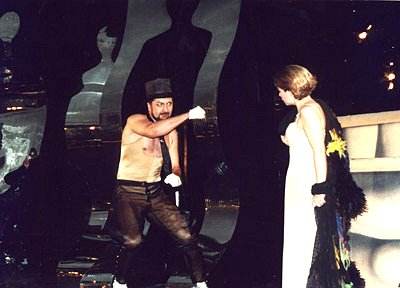

Mikhail Davydov gave an equally committed performance as Dr Schoen – whose love for Lulu is internalised, intellectualised, and inert, and whose tragedy is that he can offer her nothing except his attention and fine words. Mikhail Seryshev’s self-obsessed Artist was a super characterisation, neatly contrasted by Dmitri Kalin’s adonistic and well-sing Athlete – who had some top-ranking business with the elastic figure of Ilya Ilin as Lulu’s hyperactive schoolboy lover, forever being hurled behind bits of scenery by rival admirers. Real-life champion body-builder Maxim Losev played Jack The Ripper as a mute – he acts as the reincarnation of Schoen, seeking revenge on Lulu, and Schoen sings the final scene.

The dishevelled reprobate Schigolch is one of the few who does not prey upon Lulu, and his shuffling sordidness was a gift to able character bass Dmitri Ovchinnikov. Perhaps the only admirer whose love for Lulu is selfless is Countess Geschwitz – her "failing" is not of her own making, that she is a lesbian. This was the latest in a series of astonishing portrayals by Svetlana Rossiyskaya, whose final chilling murder-scene was one of the vocal highlights of an evening already spangled with outstanding performances. Many of the cast also appeared in other supporting roles, where Marina Karpachenko and Denis Kirpanev also shone amongst an all-star cast.Conductor Vladimir Ponkin brought together this colossal musical undertaking – in the Cerha completion of Act 3. The orchestra is hardly recognisable as the same ensemble who teetered precipitously through Verdi only five years ago, in this young company – this was world-class playing which richly deserves to be recorded. A special word of praise is due to Sergey Chechetko, whose brilliant and sensitive playing of the piano part illustrated the general outstanding standard of all the playing. On the eve of the performance, Ponkin heard that he had received a Golden Mask Award for the production, Best Opera Conductor – an outstanding achievement when Valery Gergiev is another nominee, and richly deserved for this phenomenal achievement.

Lulu goes on tour to the Ravenna Festival this summer, along with other works in the Helikon repertoire.

Neil McGowan

The Helikon Opera is Moscow’s resident full-time avant-garde opera ensemble, founded by producer Dmitri Bertmann in 1993. They perform in the highly un-ideal circumstances of a C19th aristocratic home adjacent to the Moscow Conservatoire, whose listed-building status precludes the installation of conventional stage equipment. A new stage and backstage facilities are planned for 2007, in a subterranean development beneath the present building.

Return to:

Return to: