S & H Recital Review

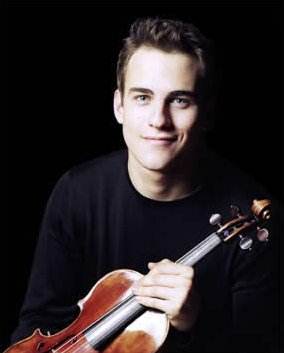

Tartini, Fribbins, Brahms, Brown, Saint-Saëns, Jack Liebeck (violin), Katya Apekisheva (paino), Purcell Room, 29th April 2003 (MB)

Great recitals are often, though not always, married to great musical partnerships. Orkis and Mutter, Markham and Norman and, in a generation past, Richter and Oistrakh and Moore and Fischer-Dieskau are, or were, outstanding musical partnerships where no one artist had a hegemony over the over. I list the pianist first in every case because so often in recital the pianist can be a dominating presence (as a recent Wigmore Hall recital given by Ilya Gringolts and Boris Berezovsky showed). In none of the above cases is that true, and in Apekisheva’s and Liebeck’s recital at the Purcell Room it was refreshing to find a young pair of outstanding musicians following in the footsteps of these great artists; theirs was a partnership in every sense of the word.However, if this was by no means a faultless recital it reached a very high level of artistry and inspiration, belying both the age and relative concert experience of both musicians. An incandescent account of Saint-Saëns’ Sonata No.1 in D minor closed the recital but it had begun much less well with Tartini’s ‘Devil Trill Sonata’. Using Kreisler’s arrangement of the work Liebeck took some time to settle, his pace not always being ideally poised between the work’s rhetoric and panache. Yet, his view of the piece is highly romantic – and he produced a wide-bodied sound – with splendid tonal weight given to the G-string – that was both refined and expressive. Some of the Largo’s ‘infernal siciliana’ wasn’t quite defined fully enough and occasionally the demonic ambivalence of the Allegro was underplayed. The fiendish trills of the Cadenza were waspish even if his double-stopping was less secure than it might have been.

Peter Fribbins’ ‘…that which echoes in eternity’ proved to be the turning point in this recital. Powerful and turbulent in equal measure, it was often a performance given huge dynamic range, and yet every note remained audible throughout. Apekisheva’s almost destructive clusters at the low end of the keyboard were superbly articulated, and what beautifully controlled pedalling this pianist has, but equally memorable was the precision of Liebeck’s sustained high notes on the E-string, as breathless as a whisper, yet so utterly even in tone. Fribbin’s piece takes as its inspiration Canto VI from Dante’s Inferno and how wonderfully both musicians conveyed its lugubrious and unsettling sound world.

Brahms’ D minor sonata ended the first half and for the first time one was able to appreciate how remarkable Liebeck is as a violinist. Technically, he was superb but what was extraordinary was how far his sound and intonation changed to reflect the innate lyricism and introspection of this work; the big sound he had produced in the Tartini was here melded into something aristocratic and subtle. If the full-blooded playing owed something to a wider than usual vibrato his control of it remained impeccable. In many ways – especially with the sovereign control over the almost gilded sound he produced - this was as close to a Milstein performance of the work as one is likely to hear today.

James Francis Brown’s Violin Sonata shares with the Fribbins a seductive, if hardly challenging, tonality. The composer originally intended the piece to be a group of three independent movements and what he had written for the middle section was removed before the work’s premiere at the 2002 Cheltenham Festival. Ironically, it is the completed work’s central Presto (which received its premiere at this recital) which is the most striking part of the sonata combining elements of barely suppressed violence within a broader spatial pulse. It contrasts radically with the outer movements, and beautifully played though they were, what remains memorable is the energetic virtuosity of the Presto – especially when so beguilingly played as it was here.

Quite why Saint-Saëns superb Violin Sonata No.1 is so neglected is a puzzle. Liebeck and Apekisheva gave as compelling a performance of it as I have heard, in either concert or on record. Liebeck produced the warmest of tones for the Adagio, splintered with a meditative radiance that trod carefully between the parameters of the intense and the bathetic. When it came to the Allegro moderato and Allegro molto (the composer, unusually, welds the four movements into two parts) both pianist and violinist ricocheted octaves through a ball-game of exhilarating virtuosity. The moto perpetuo finale of the sonata was delivered with breathtaking control and panache to end a performance of pure, spontaneous musicianship.

Liebeck is undoubtedly a major talent (although he has yet to graduate from the RCM), and with Apekisheva, they combine to form an extremely fine partnership where the rapport is absolute. I expect them to become a great one. This recital would have shamed many by bigger names unwilling to risk the inclusion of new works with established repertoire. As it was, these two musicians brought it off with consummate artistry.

Marc Bridle

Return to:

Return to: